Offer a cutting-edge security system, and you’ll suffer no shortage of customers who want it installed. But before our age of concealed cameras, motion sensors, retinal scanners, and all the other advanced and often unsettling technologies known only to industry insiders, how did owners of large, expensive, and even royalty-housing properties buy peace of mind? We find one particularly ingenious answer by looking back about 400 years ago, to the wooden castles and temples of 17th-century Japan.

“For centuries, Japan has taken pride in the talents of its craftsmen, carpenters and woodworkers included,” writes Sora News 24’s Casey Baseel. “Because of that, you might be surprised to find that some Japanese castles have extremely creaky wooden floors that screech and groan with each step. How could such slipshod construction have been considered acceptable for some of the most powerful figures in Japanese history? The answer is that the sounds weren’t just tolerated, but desired, as the noise-producing floors functioned as Japan’s earliest automated intruder alarm.”

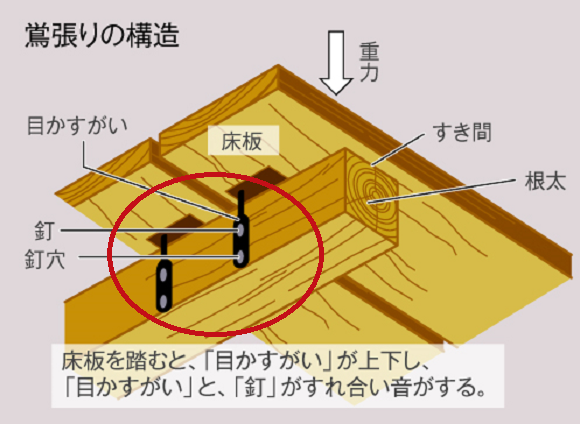

In these specially engineered floors, “planks of wood are placed atop a framework of supporting beams, securely enough that they won’t dislodge, but still loosely enough that there’s a little bit of play when they’re stepped on.” And when they are stepped on, “their clamps rub against nails attached to the beams, creating a shrill chirping noise,” rendering stealthy movement nearly impossible and thus making for an effective “countermeasure against spies, thieves, and assassins.”

According to Zen-Garden.org, you can still find — and walk on — four such uguisubari, or “nightingale floors,” in Kyoto: at Daikaku-ji temple, Chio-in temple, Toji-in temple, and Ninomura Palace.

If you can’t make it out to Kyoto any time soon, you can have a look and a listen to a couple of those nightingale floors in the short clips above. Then you’ll understand just how difficult it would have been to cross one without alerting anyone to your presence. This sort of thing sends our imaginations straight to visions of highly trained ninjas skillfully outwitting palace guards, but in their day these deliberately squeaky floors floors also carried more pleasant associations than that of imminent assassination. As this poem on Zen-Garden.org’s uguisubari page says says:

鳥を聞く

歓迎すべき音

鴬張りを渡る

A welcome sound

To hear the birds sing

across the nightingale floor

Related Content:

Omoshiroi Blocks: Japanese Memo Pads Reveal Intricate Buildings As The Pages Get Used

A Virtual Tour of Japan’s Inflatable Concert Hall

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.