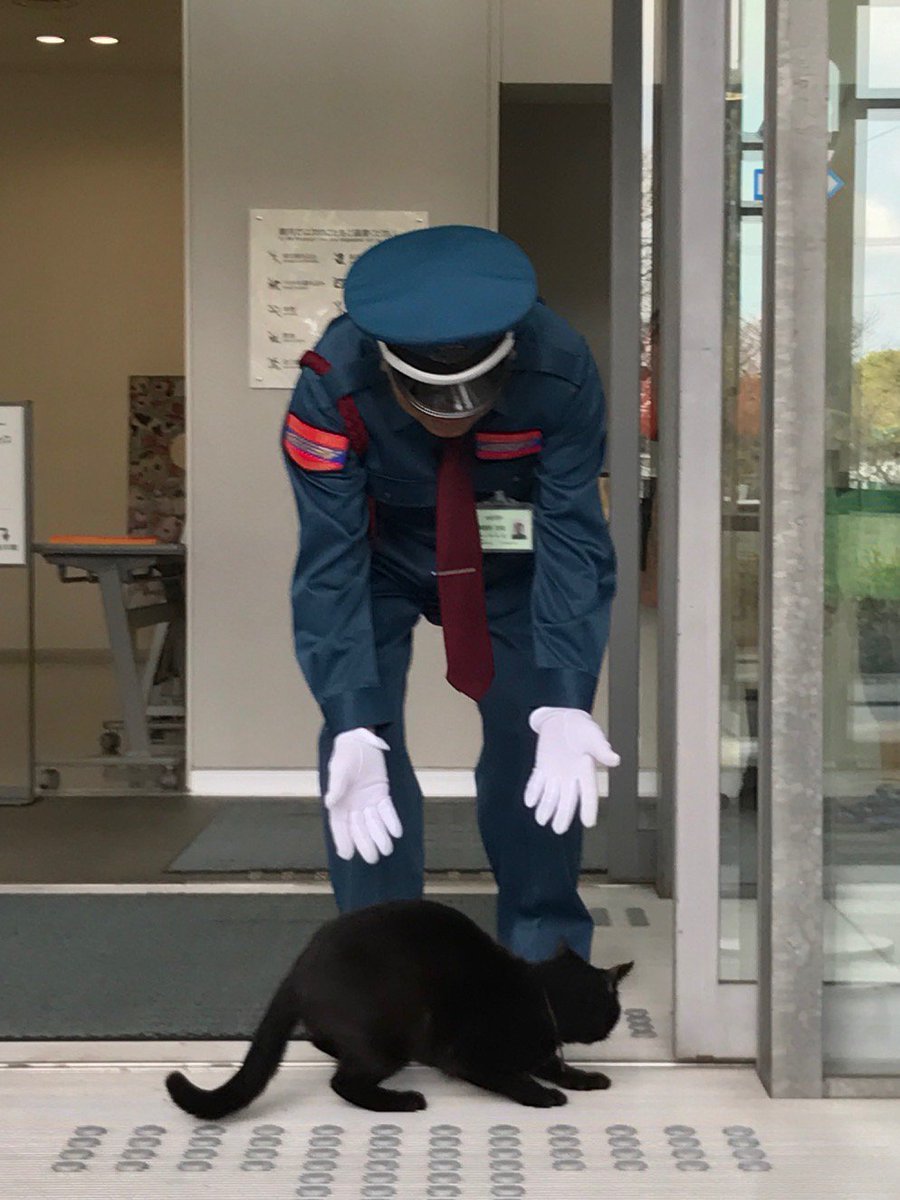

Image by Darren Swim, via Wikimedia Commons

Everyone knows the punchline “more cowbell” from SNL’s affectionate jab at the Blue Öyster Cult’s enthusiasm. But how many people know the true story of “more barn”?

Too precious few, I’d say.

It’s a classic from that icon of classic rock, Neil Young, a yarn—as told by Graham Nash—that defies parody, and beautifully illustrates the absurdity of Neil Young’s commitment to raw, rustic authenticity. For his dedicated fans, Neil’s ramshackle methods always yield worthy results. Even when he’s off, he’s so damned into it, it’s hard to ever fault him.

And when he’s on—in masterpieces like 1972’s Harvest—Neil does no wrong. His talents stretch beyond intensely impassioned songcraft and delivery to a holistic appreciation of sound in all its forms (and a loathing for technology that does sound an injustice).

In the interview above with NPR’s Terry Gross after the publication of his book Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life, Young’s erstwhile CSNY bandmate Nash recounts the day Young first played him Harvest:

The man is totally committed to the muse of music. And he’ll do anything for good music. And sometimes it’s very strange. I was at Neil’s ranch one day just south of San Francisco, and he has a beautiful lake with red-wing blackbirds. And he asked me if I wanted to hear his new album, “Harvest.” And I said sure, let’s go into the studio and listen.

Oh, no. That’s not what Neil had in mind. He said get into the rowboat.

I said get into the rowboat? He said, yeah, we’re going to go out into the middle of the lake. Now, I think he’s got a little cassette player with him or a little, you know, early digital format player. So I’m thinking I’m going to wear headphones and listen in the relative peace in the middle of Neil’s lake.

Oh, no. He has his entire house as the left speaker and his entire barn as the right speaker. And I heard “Harvest” coming out of these two incredibly large loud speakers louder than hell. It was unbelievable. Elliot Mazer, who produced Neil, produced “Harvest,” came down to the shore of the lake and he shouted out to Neil: How was that, Neil?

And I swear to god, Neil Young shouted back: More barn!

Now, whether or not that last bit is a Nash invention, it must forever remain the punchline of the story, which must always be referred to as “more barn.” But there’s no reason to think it didn’t happen just the way Nash tells it.

In the film at the top, Young listens to playback of Harvest through the barn, comments on the “natural echo” of its reverberations from yonder hillside, drinks a Coors, and lounges in the straw. (He also talks in earnest depth about the ethical and personal challenges of being a “rich hippie.”)

I’ve heard this album countless times through headphones and stereo, surround, and car speakers, but until I can yell out “more barn!” I’m convinced I have not truly heard it at all.

Related Content:

Neil Young Performs Classic Songs in 1971 Concert: “Old Man,” “Heart of Gold” & More

Neil Young Busking in Glasgow, 1976: The Story Behind the Footage

When Neil Young & Rick James Created the 60’s Motown Band, The Mynah Birds

Miles Davis Opens for Neil Young and “That Sorry-Ass Cat” Steve Miller at The Fillmore East (1970)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness