For all of the justified ire directed at certain online retailers for their anti-competitive practices, tax evasion, labor exploitation, and so on, one fact often goes unremarked upon since it seems to fall outside the usual narratives. The explosion of online retail gave purchasing power to people locked out of certain markets because of income or geography or disability, etc. Moreover, it gave people outside of traditional market demographics the opportunity to experiment with new interests in judgment-free zones.

These changes have allowed a generation of musicians access to instruments they would never have been willing or able to find in the past. For example, Fender guitars has discovered that women now account for 50 percent of all “beginner and aspirational players,” notes Rolling Stone. “The instrument-maker is adjusting its marketing focus accordingly… around a massive new audience that it’d previously been ignoring.” Walking into a music store and feeling like you’ve been ignored by the big companies may not make for an encouraging experience. But the ability to buy gear online without a hassle may be one significant reason why so many more women have taken up the instrument.

Which brings us to Sears. Yes, it’s a roundabout way to get there, but bear with me. You’ve surely heard the news by now, the venerable retail giant has gone bankrupt after 132 years in business—a casualty of predatory capitalism or bad business practices or the inevitably changing times or what-have-you. A number of eulogies have described the company’s early “catalogue shopping system” as “the Amazon of its day,” as Lila MacLellan points out at Quartz. The comparison surely fits. During its heyday, people all over the country, in the most far-flung rural areas, could order almost anything, even a house.

But a number of stories, including MacLellan’s, have also described Sears, Roebuck & Company as a great equalizer of its day for the way it busted the Jim Crow barriers black shoppers once faced. Cornell University history professor Louis Hyman has posted a thread on his Twitter and given an interview on Jezebel describing the democratizing power of the Sears Catalog in the late 19th century for black Americans, most of whom lived in rural areas (as did most Americans generally) and had to suffer discrimination from white shopkeepers, who charged inflated prices, denied sales and credit, forced black customers to wait at the back of long lines, and so on.

Hyman talks about this specific history in the video lecture above (starting at 6:24). The viciousness of segregation didn’t stop at the store. As he says, local postmasters would often refuse to sell stamps or money orders to black customers. The Sears Catalog, then, included specific instructions for giving cash directly to mail carriers. Storekeepers burned the catalogs, but still rural customers were able to get their hands on them and order what they needed, pay cash, and receive it without difficulty. A new world opened up for people previously shut out of many consumer markets, and this included, writes Chris Kjorness at Reason, turn-of-the-century musicians.

The Sears guitar, says Michael Roberts, who teaches the history of the blues at DePaul University, “was inexpensive enough that the blues artists were able to save up the money they made as sharecroppers to make that purchase.” As Kjorness puts it, “There was no Delta blues before there were cheap, readily available steel-string guitars. And those guitars, which transformed American culture, were brought to the boondocks by Sears, Roebuck & Co.”

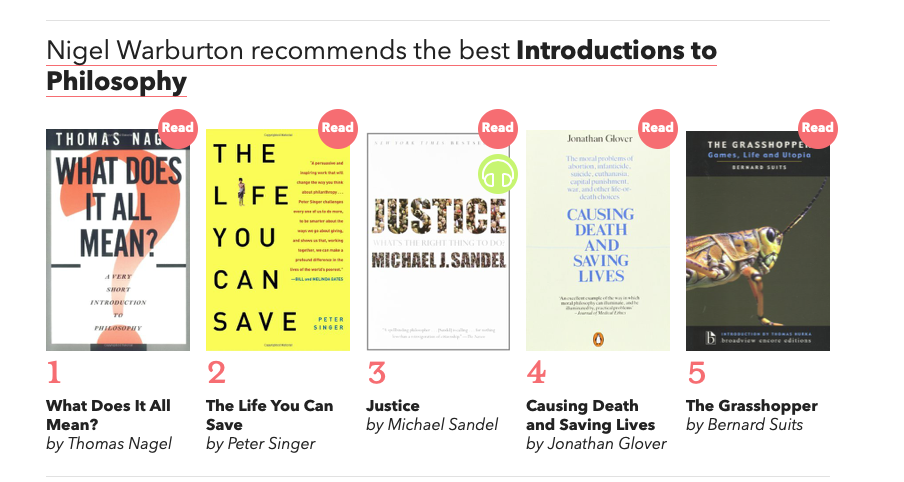

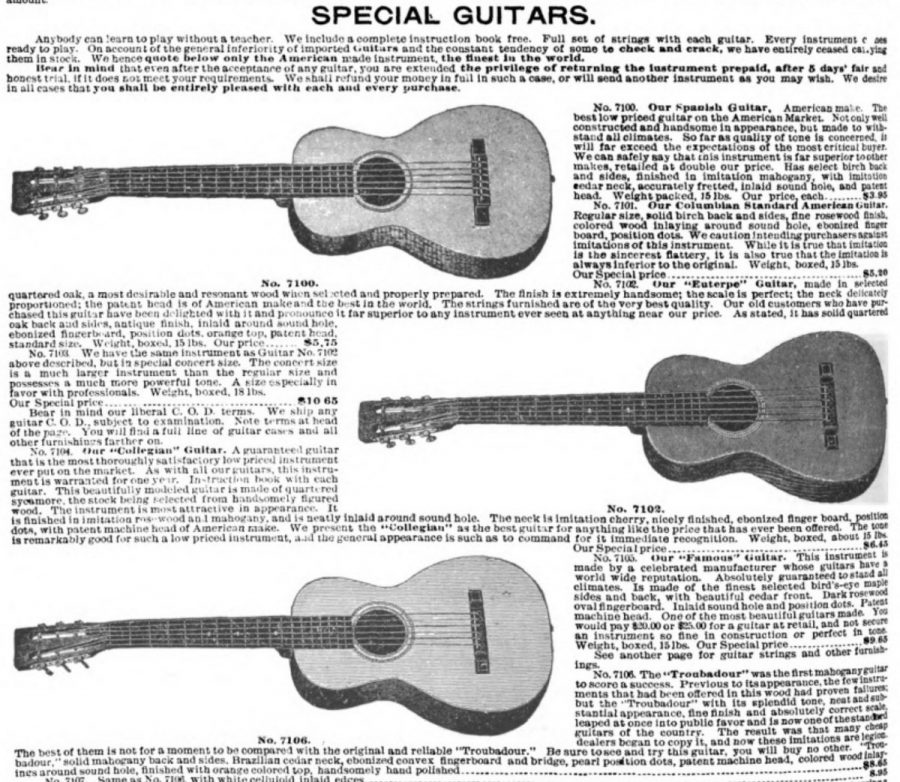

The first Sears, Roebuck catalog was published in 1888. It would go on to transform America. Farmers were no longer subject to the variable quality and arbitrary pricing of local general stores. The catalog brought things like washing machines and the latest fashions to the most far-flung outposts. Guitars first appeared in the catalog in 1894 for $4.50 (around $112 in today’s money). By 1908 Sears was offering a guitar, outfitted for steel strings, for $1.89 ($45 today), making it the cheapest harmony-generating instrument available.

Quality improved, prices went down, and bluesmen could get their instruments by mail. Most of the big names we associate with the Delta blues bought a guitar from the Sears Catalog. Guitars became such a popular item that Sears introduced their own brand, under the existing Silvertone line, in the 1930s. Later budget guitars and amplifiers sold through Sears included Danelectro, Valco, Harmony, Kay, and Teisco (all of whom, at one time or another, made Silvertones).

These brands are now known to musicians as classic roots and garage rock instruments played by the likes of Jack White, but their histories all come together with Sears (you may hear them lumped together sometimes as “the Sears guitars”). The company first supplied bluesmen and country pickers with acoustic guitars, but “once the sound of the electric guitar became that of American music,” Whet Moser writes at Chicago Magazine, “teens in garages all over started picking up axes, and Sears was there to supply them.”

Through their business deal with Nathan Daniel, they manufactured the “amp-in-case” line of Danelectro Masonite guitars, sold in stores and catalogs. These funky 50s instruments, designed for maximum cost-cutting, incorporated surplus lipstick tubes as housing for their pickups. They made such a distinctive jangly sound, thanks to the way Daniel wired them, that it became a hallmark of 50s and 60s garage rock. Often sold under the Silvertone name as well, Danelectro guitars were cheap, but well designed. (Jimmy Page has had a particular fondness for the Danelectro 59).

While the product history of Sears electric guitars is incredibly complicated, with brand names, designs, and product lines shifting from year to year, it’s enough to say that without their budget guitars and amps, many of the struggling musicians who innovated the blues and rock and roll would have been unable to afford their instruments. The story of Sears writ large can be told as the story of a market “disruptor” raising standards of living for millions of rural and urban Americans. The company’s innovative marketing and distribution schemes were also totally central to the history of American popular music.

Related Content:

History of Rock: New MOOC Presents the Music of Elvis, Dylan, Beatles, Stones, Hendrix & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness