New books on fascism are popping up everywhere, from independent presses, former world leaders like Madeleine Albright, and academics like Jason Stanley, Jacob Urowsky Professor of Philosophy at Yale University. Stanley’s latest book, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, has been described as a “vital read for a nation under Trump.” And yet, as The Guardian’s Tom McCarthy writes, one of the ironies Stanley points out is that—despite the widespread currency of the term these days—fascism succeeds by making “talk of fascism… seem outlandish.”

Is it?

The word has certainly been diluted by years of misuse. Umberto Eco wrote in his 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism” that “fascist” as an epithet was casually thrown around “by American radicals… to refer to a cop who did not approve of their smoking habits.” When every authority figure who seems to abuse power gets labeled a fascist, the word loses its explanatory power and its history disappears. But Eco, who grew up under Mussolini and understood fascist Europe, insisted that fascism has clearly recognizable, and portable, if not particularly coherent, features.

“The fascist game can be played in many forms,” Eco wrote, depending on the national mythologies and cultural history of the country in which it takes root. Rather than a single political philosophy, Eco argued, fascism is “a collage… a beehive of contradictions.” He enumerated fourteen features that delineate it from other forms of politics. Like Eco, Stanley also identifies some core traits of fascism, such as “publicizing false charges of corruption,” as he writes in his book, “while engaging in corrupt practice.”

In the short New York Times opinion video above, Stanley summarizes his “formula for fascism”—a “surprisingly simple” pattern now repeating in Europe, South America, India, Myanmar, Turkey, the Philippines, and “right here in the United States.” No matter where they appear, “fascist politicians are cut from the same cloth,” he says. The elements of his formula are:

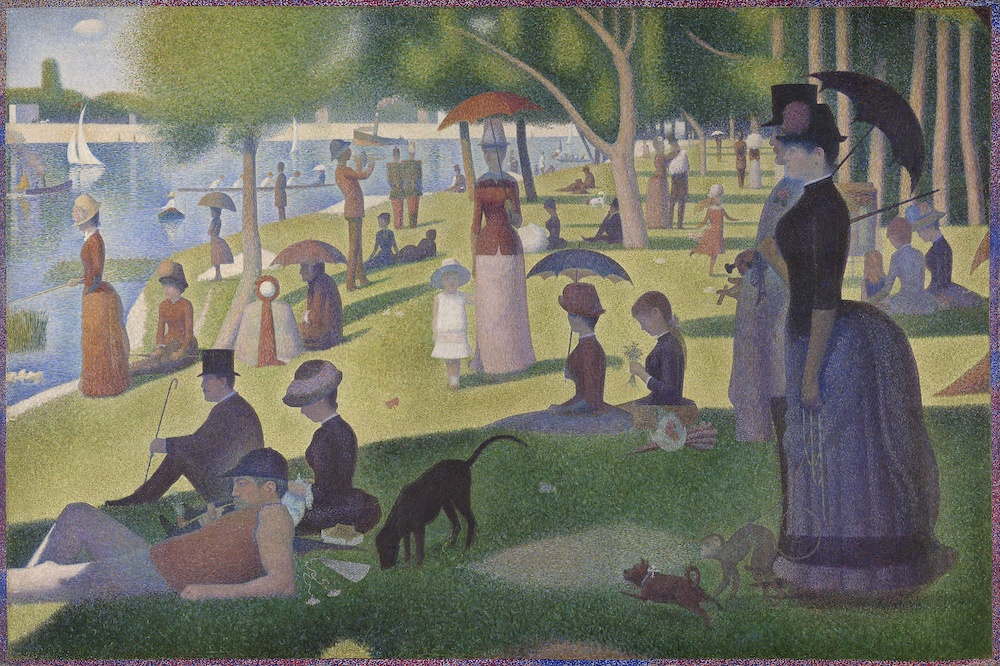

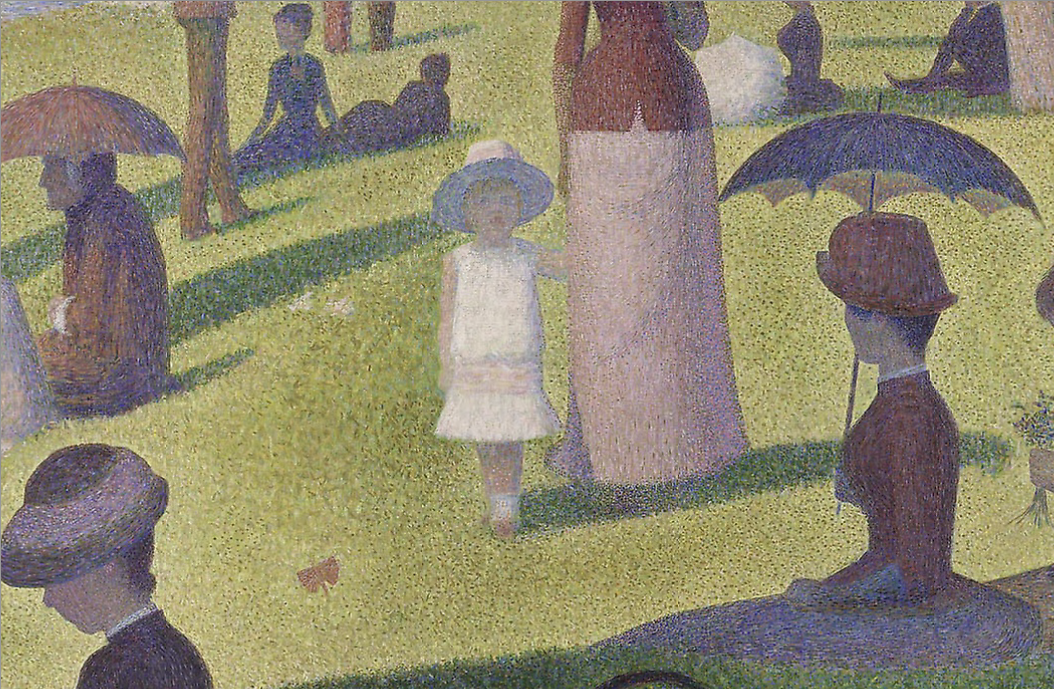

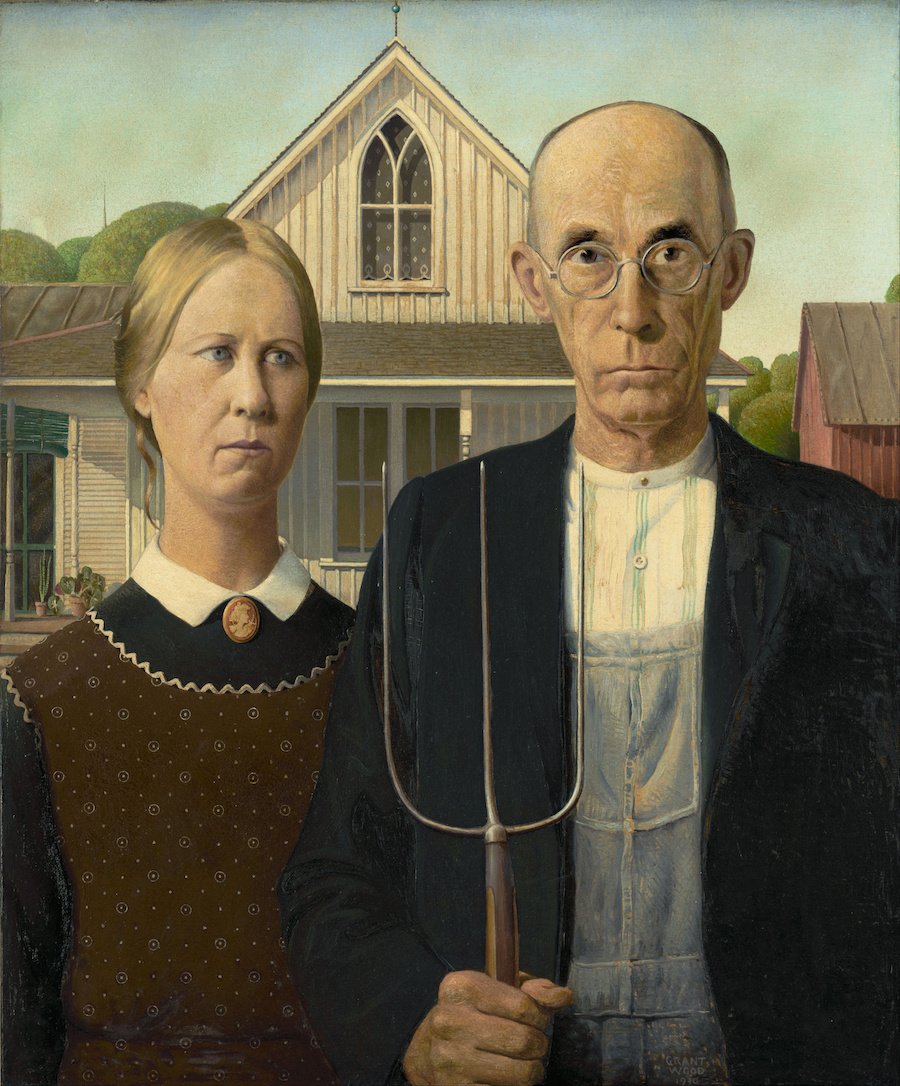

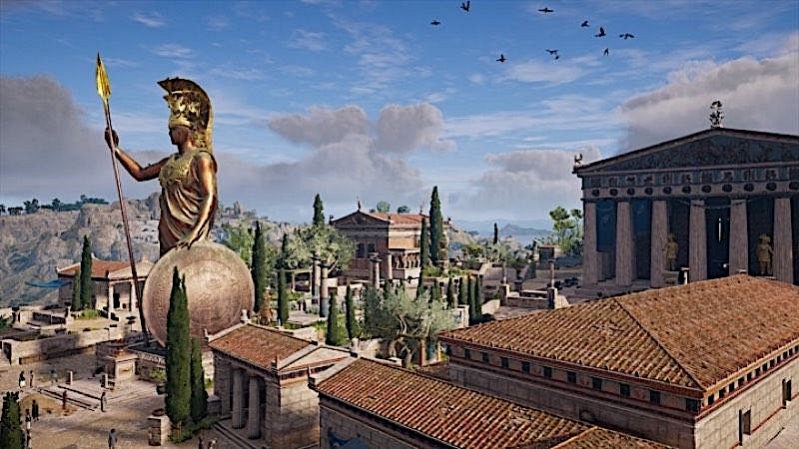

1. Conjuring a “mythic past” that has supposedly been destroyed (“by liberals, feminists, and immigrants”). Mussolini had Rome, Turkey’s Erdoğan has the Ottoman Empire, and Hungary’s Viktor Orban rewrote the country’s constitution with the aim of “making Hungary great again.” These myths rely on an “overwhelming sense of nostalgia for a past that is racially pure, traditional, and patriarchal.” Fascist leaders “position themselves as father figures and strongmen” who alone can restore lost greatness. And yes, the fascist leader is “always a ‘he.’”

2. Fascist leaders sow division; they succeed by “turning groups against each other,” inflaming historical antagonisms and ancient hatreds for their own advantage. Social divisions in themselves—between classes, religions, ethnic groups and so on—are what we might call pre-existing conditions. Fascists may not invent the hate, but they cynically instrumentalize it: demonizing outgroups, normalizing and naturalizing bigotry, stoking violence to justify repressive “law and order” policies, the curtailing of civil rights and due process, and the mass imprisonment and killing of manufactured enemies.

3. Fascists “attack the truth” with propaganda, in particular “a kind of anti-intellectualism” that “creates a petri dish for conspiracy theories.” (Stanley’s fourth book, published by Princeton University Press, is titled How Propaganda Works.) We would have to be extraordinarily naïve to think that only fascist politicians lie, but we should focus here on the question of degree. For fascists, truth doesn’t matter at all. (As Rudy Giuliani says, “truth isn’t truth.”) Hannah Arendt wrote that fascism relies on “a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth.” She described the phenomenon as destroying “the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world.… [T]he category of truth verses falsehood [being] among the mental means to this end.” In such an atmosphere, anything is possible, no matter how previously unthinkable.

Using this rubric, Stanley links the tactics and statements of fascist leaders around the world with those of the current U.S. president. It’s a persuasive case that would probably sway earlier theorists of fascism like Eco and Arendt. Whether he can convince Americans who find talk of fascism “outlandish”—or who loosely use the word to describe any politician or group they don’t like—is another question entirely.

FYI: You can download Stanley’s new book How Fascism Works, as a free audiobook if you want to try out Audible.com’s no-risk, 30-day free trial program. Find details here.

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness