Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The history of science, like most every history we learn, comes to us as a procession of great, almost exclusively white, men, unbroken but for the occasional token woman—well-deserving of her honors but seemingly anomalous nonetheless. “If you believe the history books,” notes the Timeline series The Matilda Effect, “science is a guy thing. Discoveries are made by men, which spur further innovation by men, followed by acclaim and prizes for men. But too often, there is an unsung woman genius who deserves just as much credit” and who has been overshadowed by male colleagues who grabbed the glory.

In 1993, Cornell University historian of science Margaret Rossiter dubbed the denial of recognition to women scientists “the Matilda effect,” for suffragist and abolitionist Matilda Joslyn Gage, whose 1893 essay “Woman as an Inventor” protested the common assertion that “woman… possesses no inventive or mechanical genius.” Gage wrote that “even the United States census” failed “to enumerate her among the inventors of the country.” Such assertions, Gage proceeded to demonstrate, “are carelessly or ignorantly made… although woman’s scientific education has been grossly neglected, yet some of the most important inventions of the world are due to her.”

Over 100 years later, Rossiter’s tenacious work in unearthing the contributions of U.S. women scientists inspired the History of Science Society to name a prestigious prize after her. The Timeline series profiles of the few of the women whom it describes as prime examples of the Matilda effect, including Dr. Lise Meitner, the Austrian-born physicist and pioneer of nuclear technology who escaped the Nazis and became known in her time as “the Jewish Mother of the Bomb,” though she had nothing to do with the atomic bomb. Instead, “Meitner led the research that ultimately discovered nuclear fission.” But Meitner would become “little more than a footnote in the history of Nazi scientists and the birth of the Atomic age.”

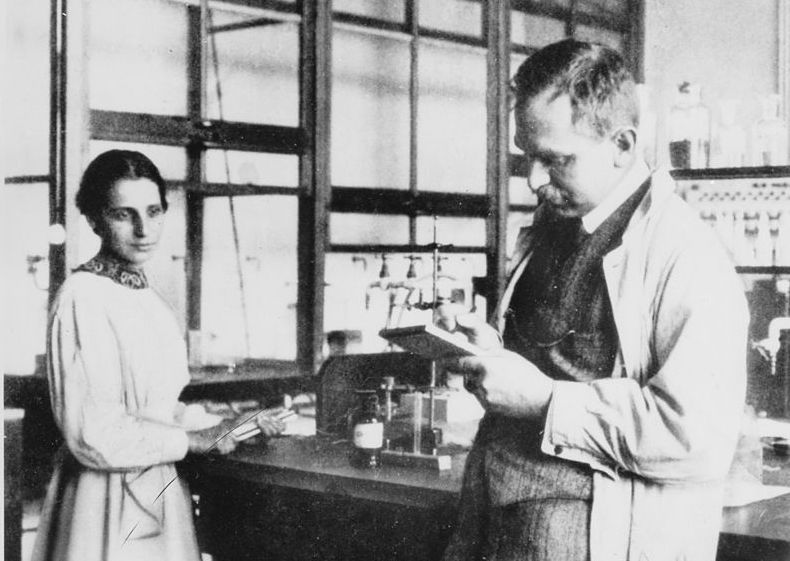

Instead, Meitner’s colleague Otto Hahn received the accolades, a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and “renown as the discoverer of nuclear fission. Meitner, who directed Hahn’s most significant experiments and calculated the energy release resulting from fission, received a few essentialist headlines followed by decades of obscurity.” (See Meitner and Hahn in the photo above.) Likewise, the name of Alice Augusta Ball has been “all but scrubbed from the history of medicine,” though it was Ball, an African American chemist from Seattle, Washington, who pioneered what became known as the Dean Method, a revolutionary treatment for leprosy.

Ball conducted her research at the University of Hawaii, but she tragically died at the age of 24, in what was likely a lab accident, before the results could be published. Instead, University President Dr. Arthur Dean, who had co-taught chemistry classes with Ball, continued her work. But he failed “to mention Ball’s key contribution” despite protestations from Dr. Harry Hollmann, a surgeon who worked with Ball on treating leprosy patients. Dean claimed credit, and published their work under his name. Decades later, “the scant archival trail of Alice Ball was rediscovered…. In 2000, a plaque was installed at the University of Hawaii commemorating Ball’s accomplishments.”

Other women in the Matilda effect series include bacterial geneticist Esther Lederberg, who made amazing discoveries in genetics that won her husband a Nobel Prize; Irish astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967, but was excluded from the Nobel awarded to her thesis supervisor Antony Hewish and astronomer Martin Ryle. A similar fate befell Dr. Rosalind Franklin, the chemist excluded from the Nobel awarded to her colleagues James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins for the discovery of DNA.

These prominent examples are but the tip of the iceberg when it comes to women who made significant contributions to scientific history and were rewarded by being written out of it and denied awards and recognition in their lifetime. For more on the history of U.S. women in science and the social forces that worked to exclude them, see Margaret Rossiter’s three-volume Women Scientists in America series: Struggles and Strategies to 1940, Before Affirmative Action, 1940–1972, and Forging a New World since 1972. And read Timeline’s Matilda Effect series of articles here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness