Image by Thierry Ehrmann via Flickr Commons

Sometimes when confronted with strange new ideas, people will exclaim, “you must be on drugs!”—a charge often levied at philosophers by those who would rather dismiss their ideas as hallucinations than take them seriously. But, then, to be fair, sometimes philosophers are on drugs. Take Jean-Paul Sartre. “Before Hunter S. Thompson was driving around in convertibles stocked full of acid, cocaine, mescaline and tequila,” notes Critical Theory, Sartre almost approached the gonzo journalist’s habitual intake.

According to Annie Cohen-Solal, who wrote a biography of Sartre, his daily drug consumption was thus: two packs of cigarettes, several tobacco pipes, over a quart of alcohol (wine, beer, vodka, whisky etc.), two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, a boat load of barbiturates, some coffee, tea, and a few “heavy” meals (whatever those might have been).

These details should not unduly influence our reading of Sartre’s work. Like Thompson, no matter how physically debilitating the booze and drugs might have been for him, they didn’t seem to cramp his productivity or intellectual vigor. But his one and only experience with mescaline almost sent him careening over the edge, and certainly contributed to an important motif in his work afterward.

While working on a book about the imagination, Sartre sought to have an hallucinatory experience. He got the chance in 1935 when an old friend, Dr. Daniel Lagache, invited him into an experiment at Sainte-Anne’s hospital in Paris, where he was injected with mescaline and observed under controlled conditions. “Sartre does not appear to have had a bad trip in the classic sense of suffering a major and prolonged panic attack,” Gary Cox writes in his Sartre biography. “But it was not a good trip and he did not enjoy it.”

The most ill effects came afterward: “His visual faculties remained distorted for weeks.” Sartre saw houses with “leering faces, all eyes and jaws.” Clock faces took on the features of owls. He confided in his partner Simone de Beauvoir that “he feared that one day he would no longer know” whether or not these were hallucinations. They were, however, not the worst aftereffects. As Sartre told political science professor John Gerassi in a 1971 interview, crabs began to follow him around. He described the experience as “a nervous breakdown.” The crabs followed him “all the time,” he said, “I mean they followed me in the streets, into class.”

I got used to them. I would wake up in the morning and say, “Good morning, my little ones, how did you sleep?” I would talk to them all the time, or I would say, “OK guys, we’re going into class now, so we have to be still and quiet,” and they would be there, around my desk, absolutely still, until the bell rang.

This went on for a year before Sartre went to see his friend Jacques Lacan for psychoanalysis. “We concluded, “ he says, “that it was a fear of becoming alone.” While he had previously confessed a fear of sea creatures, especially crabs, that went back to his childhood, after the mescaline trip, crabs featured prominently in his work, as Peter Royle shows at Philosophy Now.

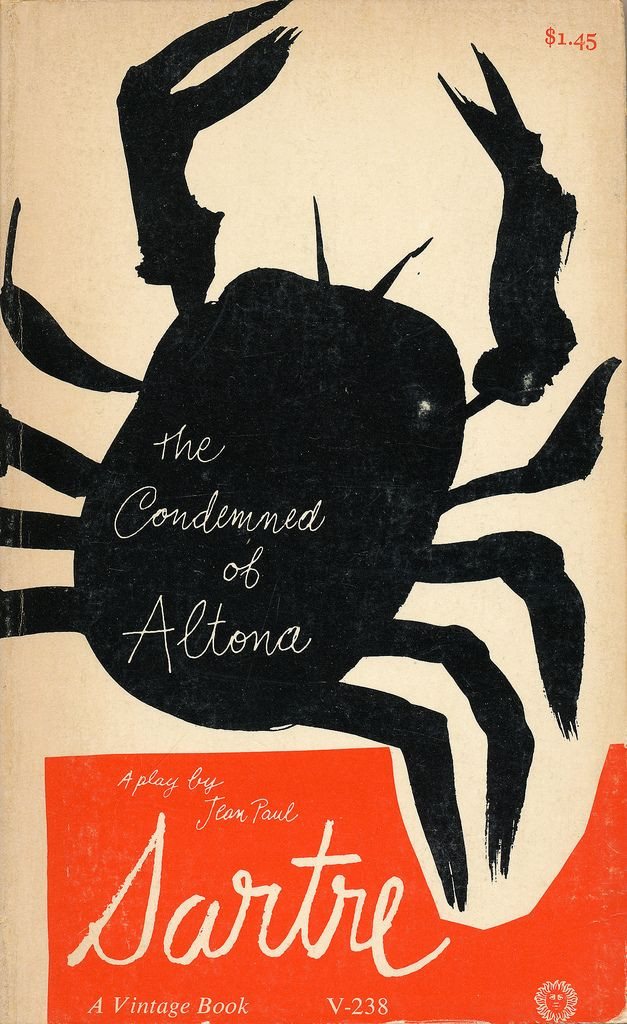

We find several references to crabs in his short story collection The Wall and in his famous essay “Existentialism is a Humanism.” Samir Chopra quotes crab passages in Sartre’s first novel Nausea. (“At first I avoided them by writing about them,” he told Gerassi, “in effect, by defining life as nausea.”) “In one of his short stories, ‘Erostratus,’” notes Royle, “Sartre creates a character, Paul Hilbert, who looks down on human beings from a height and sees them as crabs.” The most striking use of the “crab motif” comes from his 1959 play The Condemned of Altona, in which the protagonist Frantz imagines that by the Thirtieth Century, humans have become crabs sitting in judgment of the people of the Twentieth.

Crab images, Royle argues, “point to important philosophical ideas,” including “the possibility of ignominy inherent in the concept of freedom itself” and the “reprehensible ‘crabs’ who decline to assume their freedom” and thus scuttle around mindlessly in groups. Crustaceans continued to haunt the philosopher. While the effects of the mescaline eventually dissipated, “when he was feeling down,” writes Cox, Sartre would get the “recurrent feeling, the delusion, that he was being pursued by a giant lobster, always just out of sight… perpetually about to arrive.”

One of the “great, darkly comic features of Sartre folklore,” the huge, invisible lobster invites much speculation about Sartre’s mental health. But perhaps it was only the monstrous embodiment of his own feelings of mauvaise foi, given vivid form by a lingering psychotropic hangover and a daily diet of uppers and downers—a reminder of the “anxiety, anguish, dread, apprehension, fear of pain, fear of death… [and] fundamental absurdity of existence.” As Royle writes, Sartre, always fond of puns, “could only have been intrigued” by the French word for lobster, homard, which sounds like “homme-ard,” a coinage that might suggest something like “a bad man.”

Related Content:

The Drawings of Jean-Paul Sartre

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness