Perhaps more than any other postwar avant-garde American artist, Robert Rauschenberg matched, and maybe exceeded, Marcel Duchamp’s puckish irreverence. He once bought a Willem de Kooning drawing just to erase it and once sent a telegram declaring that it was a portrait of gallerist Iris Clert, “if I say so.” Rauschenberg also excelled at turning trash into treasure, repurposing the detritus of modern life in works of art both playful and serious, continuing to “address major themes of worldwide concern,” wrote art historian John Richardson in a 1997 Vanity Fair profile, “by utilizing technology in ever more imaginative and inventive ways…. Rauschenberg is a painter of history—the history of now rather than then.”

What, then, possessed this artist of the “history of now” to take on a series of drawings between 1958 and 1960 illustrating each Canto of Dante’s Inferno? “Perhaps he sensed a kindred spirit in Dante,” writes Gregory Gilbert at The Art Newspaper, “that encouraged his vernacular interpretations of the classical text and his radical mixing of high and low cultures.”

Critic Charles Darwent reads Rauschenberg’s motivations through a Freudian lens, his Inferno series a sublimation of his homosexuality and repressive childhood: “The young Rauschenberg… came to see Modernist art as a variant of his Texan parents’ fundamental Christianity.”

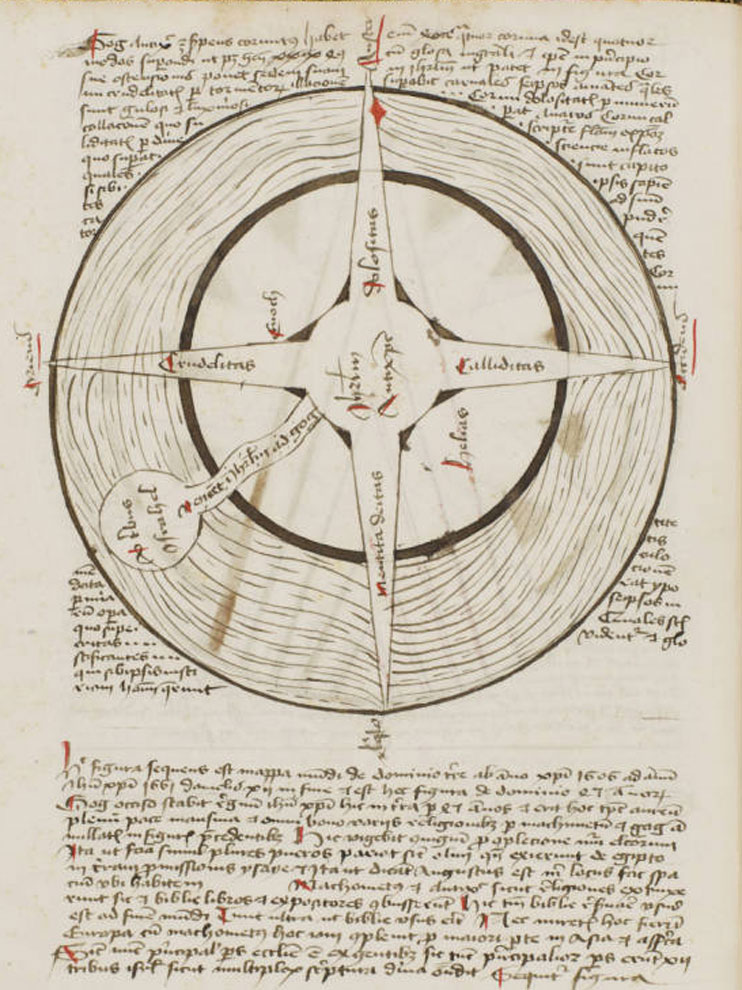

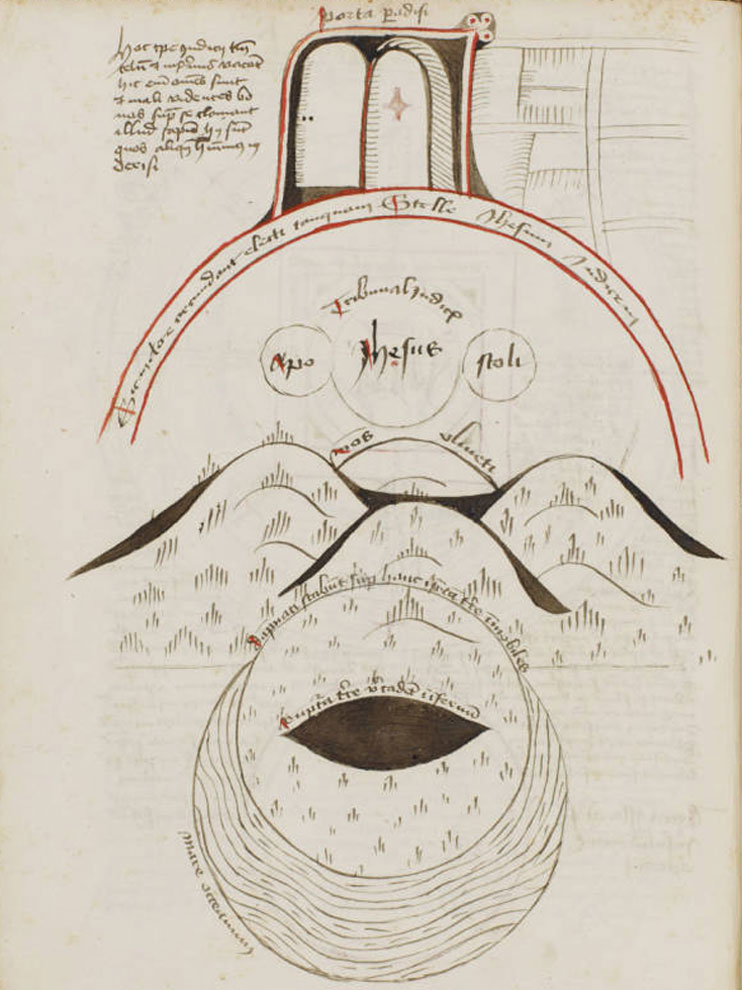

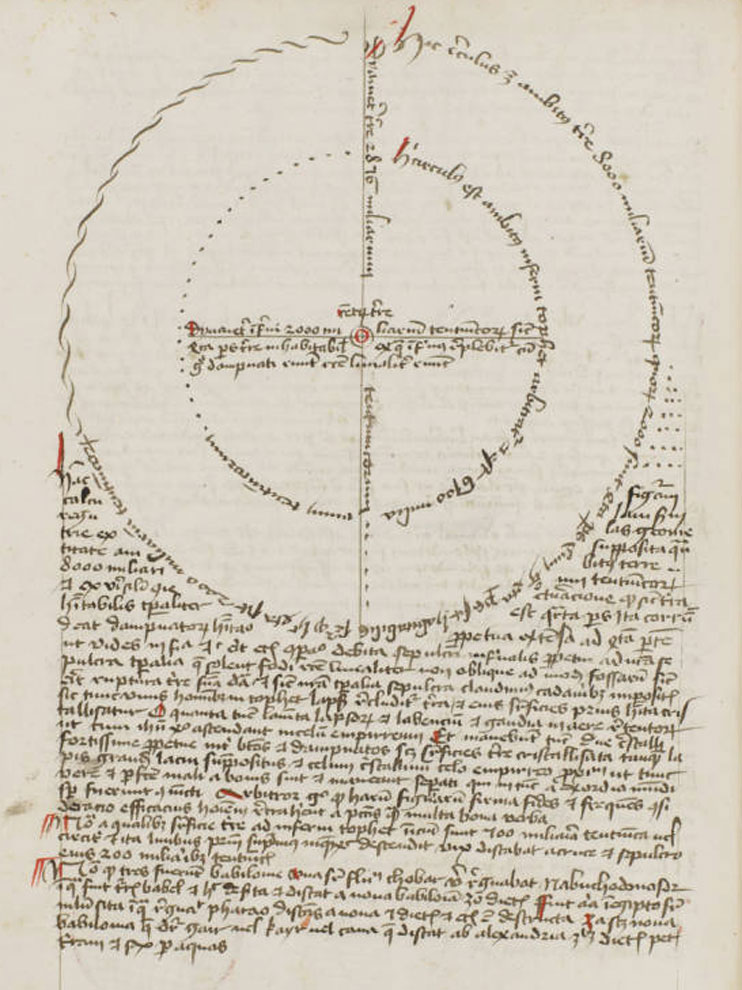

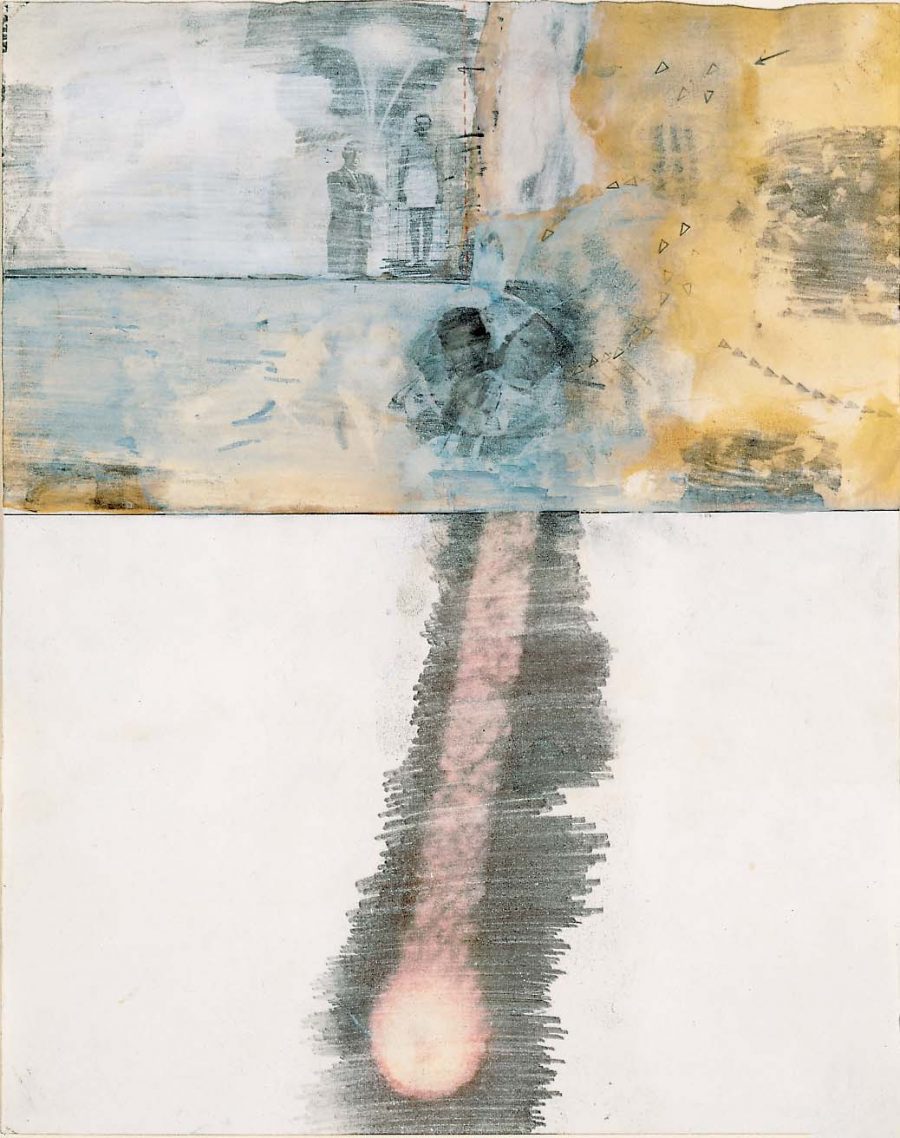

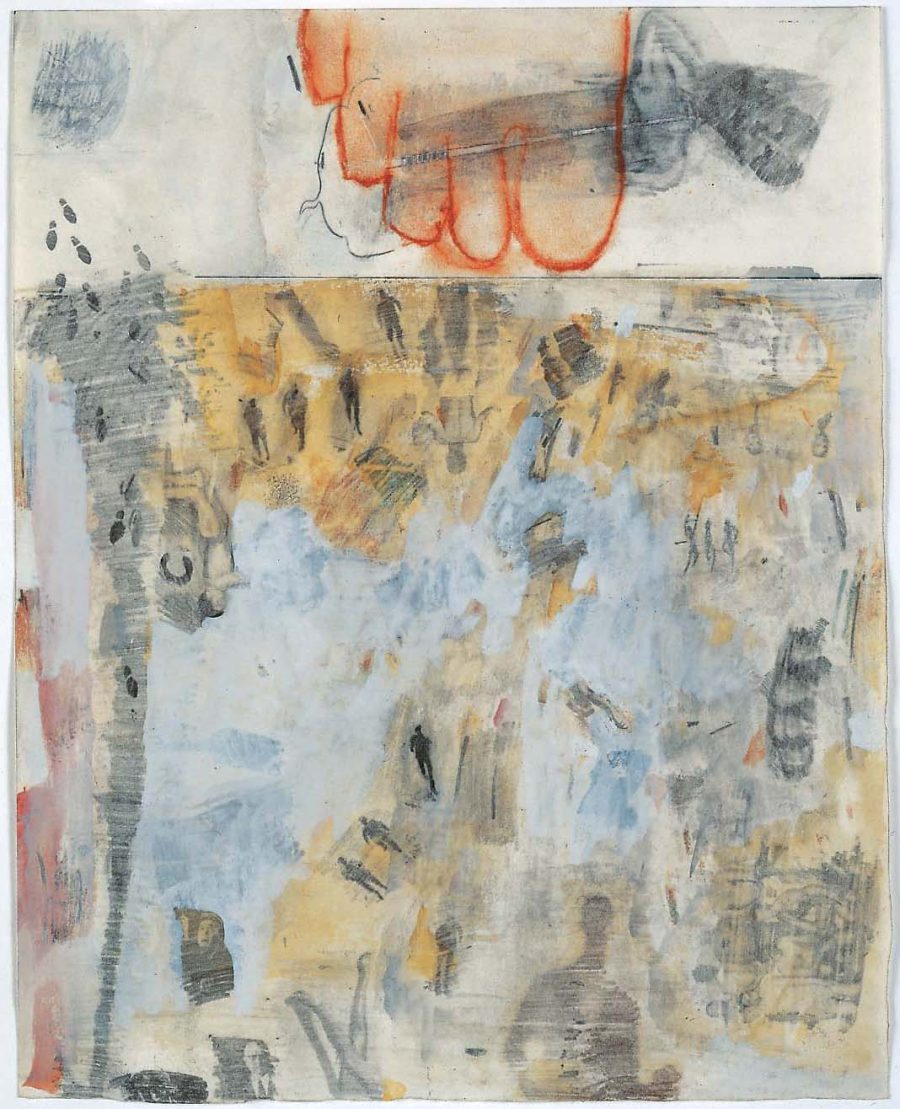

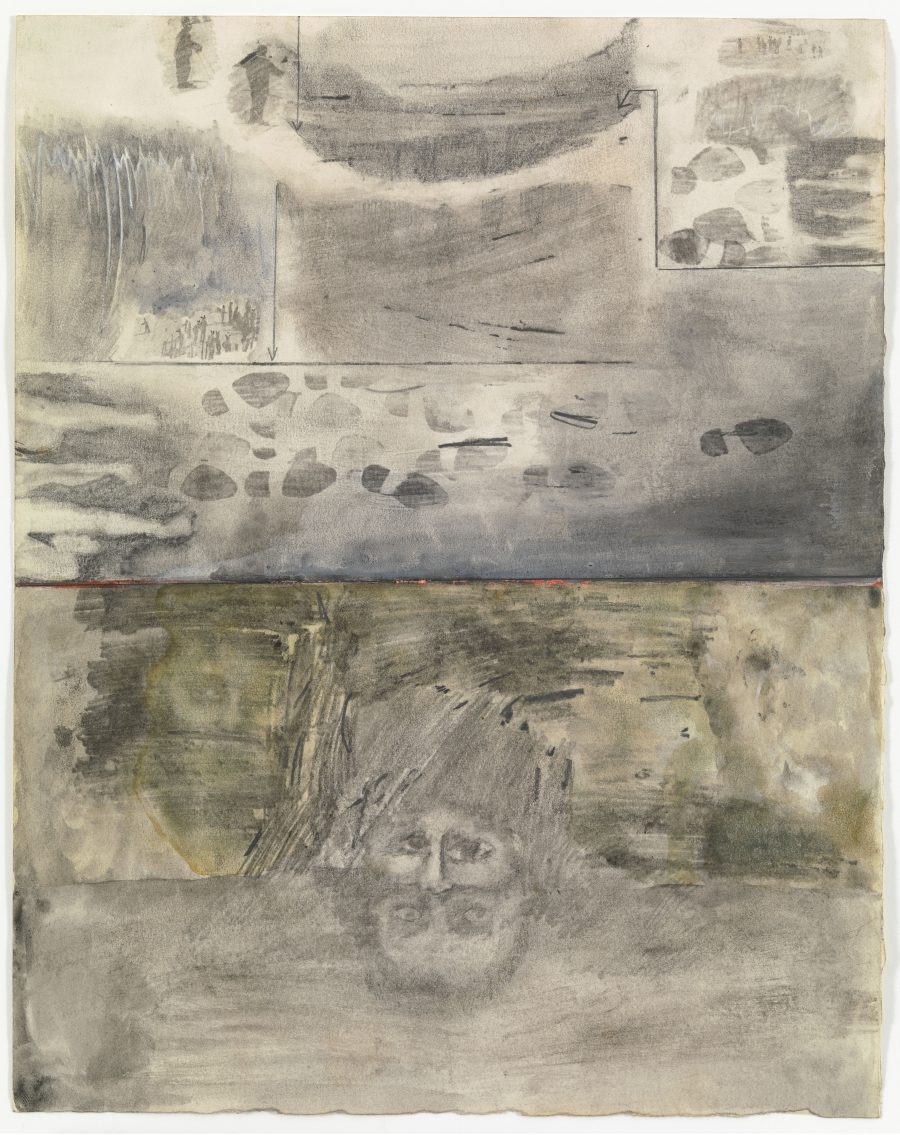

The most straightforward account has Rauschenberg conceiving the project in order to be taken more seriously as an artist. Such biographical explanations tell us something about the work, but we learn as much or more from looking at the work itself, which happens to be very much a history of now at the end of the 1950s. Though Rauschenberg based the illustrations on John Ciardi’s 1954 translation of the Divine Comedy, they were not meant to accompany the text but to stand on their own, the Italian epic—or its famous first third—providing a backdrop of ready-made ironic commentary on images Rauschenberg ripped from newspapers and magazines such as Life and Sports Illustrated.

“To create these collages,” explains MIT’s List Visual Arts Center, “he would use a solvent to adhere the images to his drawing surface, then overlay them with a variety of media, including pen, gouache (an opaque watercolor), and pencil.” Steeped in a Cold War atmosphere, the illustrations incorporate figures like John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, who, in the 50s, Gilbert writes, “served as one of Joseph McCarthy’s political henchmen during the Red Scare.” We see in Rauschenberg’s collage drawings allusions to the Civil Rights movement and the decade’s anti-Communist paranoia as well its reactionary sexual politics. “Political and sexual content… needed to be coded,” Gilbert claims, in such an “ultraconservative era.”

For example, we see a likely reference to the artist’s gay identity in the Canto XIV illustration, above. The text “describes the punishment of the Sodomites, who are condemned for eternity to walk across burning sand. Rauschenberg depicts the theme through a homoerotic image of a male nude… juxtaposed with a red tracing of the artist’s own foot.” Maybe Darwent is right to suppose that had Dante’s poem not existed, Rauschenberg “would have been the man to invent it”—or to invent its mid-20th century visual equivalent. He draws attention to the poem’s autobiographical center, its subversive humor, and its density of references to contemporary 15th century Italian politics, adapting all of these qualities for modernity.

But the illustration of Canto XIV—depicting “The Violent Against God, Nature, and Art”—also encodes Rauschenberg’s violent trampling of artistic convention. Many critics see this series as the artist’s reaction against Abstract Expressionism (like that of De Kooning). And while he “may have felt a creative kinship with Dante,” writes Gilbert, “he also admitted to the art critic Calvin Tomkins his impatience with the poet’s self-righteous morality, a statement likely directed against this Canto.” Like his 1953 Erased de Kooning Drawing, Rauschenberg’s Inferno drawings also perform an act of erasure—or the creation of a palimpsest, with Dante’s poem scratched over by the artist’s wild, childlike strokes.

In recognition of the way these illustrations repurpose, rather than accompany, the Inferno, MoMA recently commissioned an edition of Rauschenberg’s 34 drawings, accompanied not by the straight translation by Ciardi but poems by Kevin Young and Robin Coste Lewis, whose portion of the book is titled “Dante Comes to America: 20 January 17: An Erasure of 17 Cantos from Ciardi’s Inferno, after Robert Rauschenberg.” Rather than viewing the illustrations against Dante’s work itself, we can read their particular American proto-pop art character against literary “erasures” like Lewis’s “Canto XXIII,” below. See the full series of Rauschenberg’s 34 illustrations at the Rauschenberg Foundation website here.

Canto XXIII.

by Robin Coste Lewis“I Go with The Body That Was Always Mine”

Silent, one following the other,

the Fable hunted us down.

O weary mantle of eternity,

turn left, reach us down

into that narrow way in silence.College of Sorry Hypocrites, I go

with the body that was always mine,

burnished like counterweights to keep

the peace. One may still see the sort of peacewe kept. Marvel for a while over that:

the cross in Hell’s eternal exile.

Somewhere there is some gap in the wall,

pit through which we may climbto the next brink without the need

of summoning the Black Angels

and forcing them to raise us from this sink.

Nearer than hope, there is a bridgethat runs from the great circle, that crosses

every ditch from ridge to ridge.

Except—it is broken—but with care.

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

Hear Dante’s Inferno Read Aloud by Influential Poet & Translator John Ciardi (1954)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness