“Time is the warp and matter the weft of the woven texture of beauty in space, and death is the hurling shuttle.”

— Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

For the uninitiated, the warp are the plain vertical threads of a weaving or tapestry, through which the colorful, horizontal weft threads are passed, over and under, on wooden needle-shaped bobbins (or shuttles).

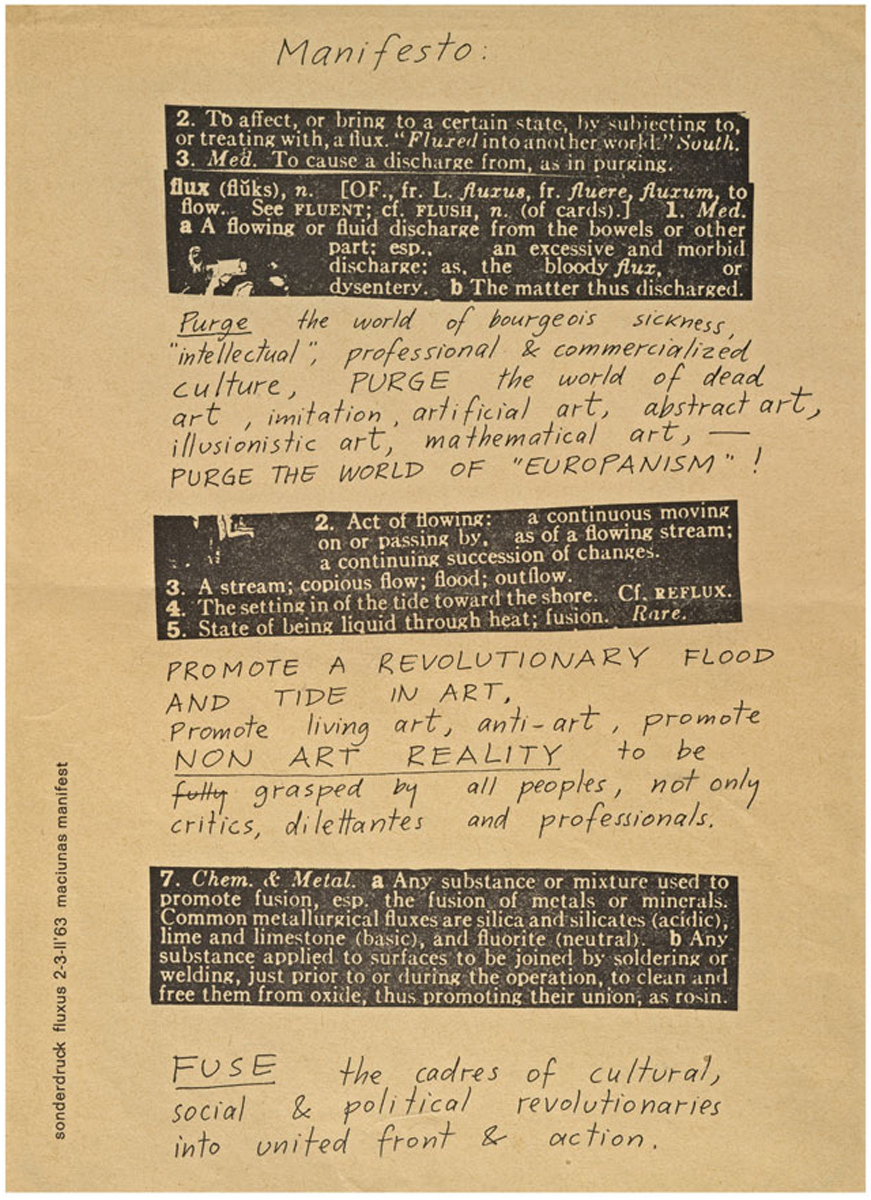

As Beatrice Grisol, Head Weaver at Paris’ venerable Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins remarks, in The Art of Making a Tapestry, above, weavers must possess a love of drawing and an abundance of imagination in order to translate an artist’s vision using silken or woolen threads.

21st century designs are more contemporary, and dying equipment more precise, but Les Gobelins’s weavers’ process remains remarkably unchanged since the days of the Sun King, Louis XIV.

As in the 17th-century, giant looms are strung with white warp threads, in readiness for the threads expert dyers have colored according to the artist’s palette.

The colored weft threads are stored on spools, and eventually portioned out onto the bobbins, which dangle from the backside of the tapestry, as the weaver works her magic, constantly checking her progress in a mirror reflecting both the project’s front side and a print of the original design.

It’s worth noting that the pronouns here are exclusively feminine. The lavish tapestries decorating Louis XIV’s court hinted at years of unsung labor by highly skilled craftswomen. Tapestries were the ne plus ultra of princely status, a testament to their owner’s erudition and taste. Louis XIV amassed some 2,650 pieces.

That’s a lot of bobbins, and a lot of hard-working female weavers.

Witness the transformation from artist Charles Le Brun’s 1664 study for the figure who would become the seated youth in The Entry of Alexander into Babylon…

…to the fully realized oil on canvas rendering from 1690…

…to its incarnation as a tapestry in the Sun King’s court:

Speeding ahead to the 21st-century, Les Gobelins appears to rival Brooklyn’s Etsy flagship as a pleasantly appointed, well lit, and highly respected Temple of Craft.

View some of the highlights of the Getty Museum’s 2016 exhibition Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV here.

Or grab your heddles and plan an in-person visit to La Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins here.

Related Content:

Artistic Maps of Pakistan & India Show the Embroidery Techniques of Their Different Regions

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on March 20 for the second installment of Necromancers of the Public Domain at The Tank. Follow her @AyunHalliday.