Many people read the German-Jewish political philosopher and journalist Hannah Arendt as something of an oracle, a secular prophet whose most famous works—her essay on the trial of Adolf Eichmann and her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism—contain secrets about our own times of high nationalist fervor. And indeed they may, but we should also keep in mind that Arendt’s insights into the horrors of Nazism did not emerge until after the war.

Arendt did not identify as Jewish during the Nazi’s rise to power, but as a fully assimilated German; she had a romantic relationship with her professor Martin Heidegger, who became a doctrinaire Nazi, and she seemed to have little understanding of German antisemitism during the thirties and forties. Arendt, many have alleged, sometimes seemed too close to her subject.

In such times as hers, to use the words of Wallace Stevens—a writer with his own complicated relationship to fascism—the “difficult rigor” of observing the moment means that “we reason of these things with later reason.” Arendt’s observations of Europe in the 1950s were reckonings with the recent past—she drew together strains of experience that could not always be connected during what Stevens calls the “irrational moment.” So too, intellectual observers of our own “irrational moment” may only truly understand it “with later reason.”

But if Americans wish to learn about their country’s longstanding political tendencies from Arendt’s work, it is perhaps not to her writing on Germany or the U.S.S.R. that we should turn, but to her work on the U.S., much of which is reflected in typed drafts of essays and lectures, correspondence, and notes contained at the Library of Congress’s Hannah Arendt Papers collection. All of the collection has been digitized, and some of those scans are online. Finding out which documents have been uploaded and which only remain viewable onsite takes a little digging around in the catalog, but it is work that pays off for those with a genuine interest in the fascinating turns of Arendt’s thought.

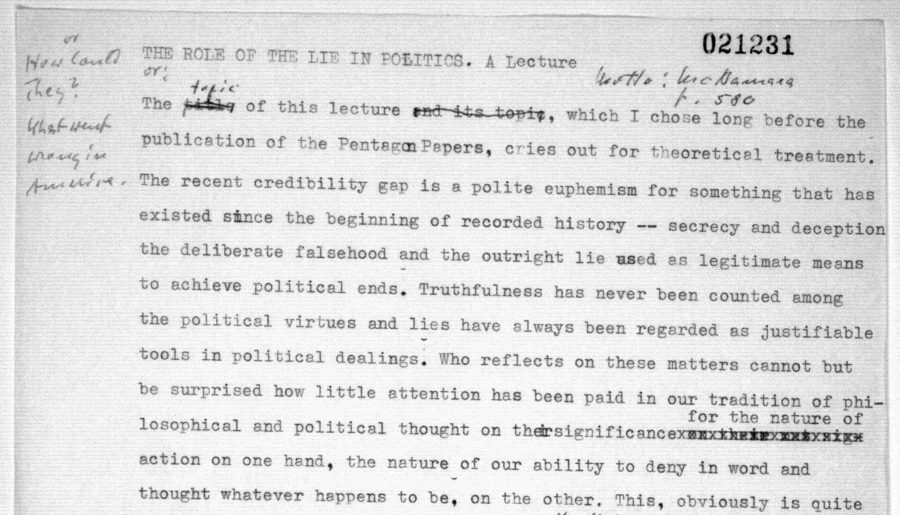

We may turn to essays such as 1971’s “Lying in Politics,” written after the release of the Pentagon Papers, notes Brain Pickings, and “included in Crises of the Republic—a collection of Arendt’s timelessly insightful and increasingly timely essays on politics [and] civil disobedience.” As Arendt writes in an earlier lecture that preceded “Lying in Politics”—with the earlier title “The Role of the Lie in Politics” (top)—“Truthfulness has never been counted as among the political virtues.” You can view and download high-quality images of that typed lecture here, and see her revise her ideas in corrections and marginal notes.

The political lie, she writes wearily, “has existed since the beginning of recorded history.” And yet, there is something unique about its use in U.S. politics, in which “the only person likely to be an ideal victim of complete manipulation is the President of the United States.” Despite her dispassionate philosophical view, Arendt found the lies of the Vietnam War-era particularly disturbing. In the typescript page at the top, you can see a proposed subtitle penciled in at the top left corner: “How Could They? What Went Wrong in America.”

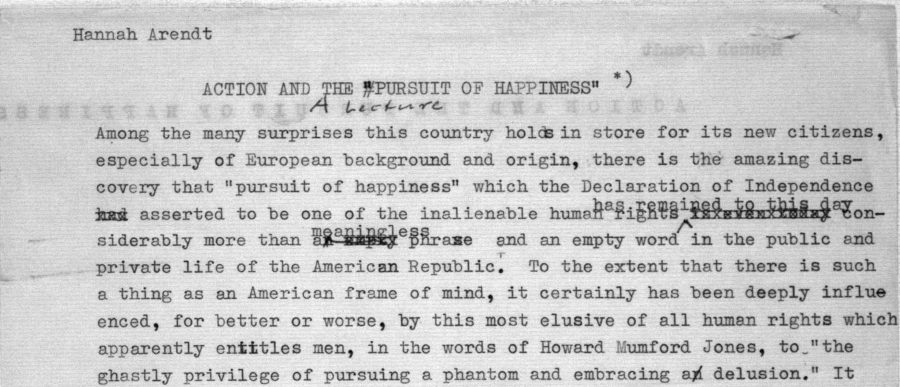

In the typed lecture above, “Action and the Pursuit of Happiness,” from 1960, Arendt remarks on the “amazing discovery” by the country’s naturalized “new citizens” that the “pursuit of happiness” remains a “more than meaningless phrase and an empty word in the public and private life of the American Republic.” This “most elusive of all human rights,” she continues, “apparently entitles men, in the words of Howard Mumford Jones, to ‘the ghastly privilege of pursuing a phantom and embracing a delusion.’”

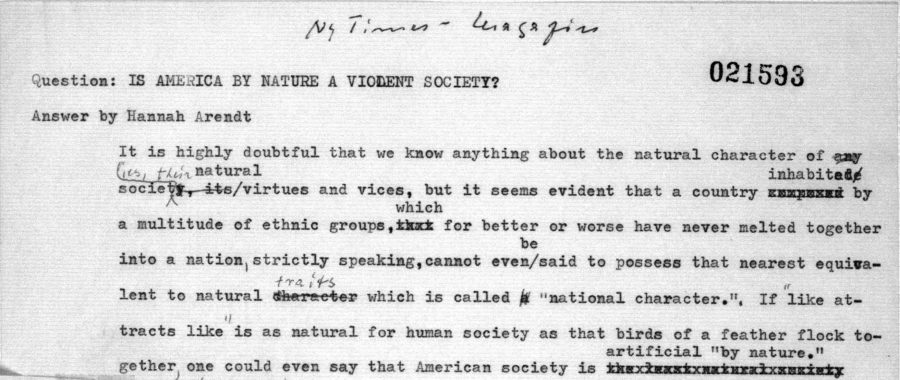

Arendt’s 1968 New York Times editorial “Is America By Nature a Violent Society,” whose typescript you can see in part above, opens with a number of assumptions about the country’s “national character,” beginning with the comment that the country’s “multitude of ethnic groups… for better or worse have never melted together into a nation.” Perhaps this is too broad a characterization. Or perhaps the U.S. as a nation is no more “artificial ‘by nature,’” in its composition than many other, much older, nations.

Arendt’s observations on her adopted land weren’t always so astute, but she did have enough critical distance from the country to closely observe it during times of crisis and see clearly what others could or would not. You’ll find many more of Arendt’s keen observations—typed in drafts and notes, scribbled in margins, and written in letters—at the Library of Congress’ Hannah Arendt Papers collection, (partly) online.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness