The most illustrious of inventors, Leonardo da Vinci, was not moved by conventional ideas about success. He took commission after commission from his wealthy, aristocratic patrons, created meticulous plans, then moved on to the next thing without finishing—as if he had learned all he needed and had no more use for the project. The works we remember him for were a tiny handful among thousands of planned designs and artwork. They have the distinction of being his major masterpieces because they happen to be completed.

Had Leonardo finished all of his proposed projects, they would fill the Louvre. He was content to leave many of his paintings unpainted, sculptures unsculpted, and inventions unbuilt—sketched out in theory in his copious notebooks, protected from theft by his ingenious cryptography, and left for future generations to discover.

One such invention, the Viola Organista, might have changed the course of musical history had Leonardo had the wherewithal or desire to build one in his lifetime. Or it might have remained a minor curiosity; there is no way to know.

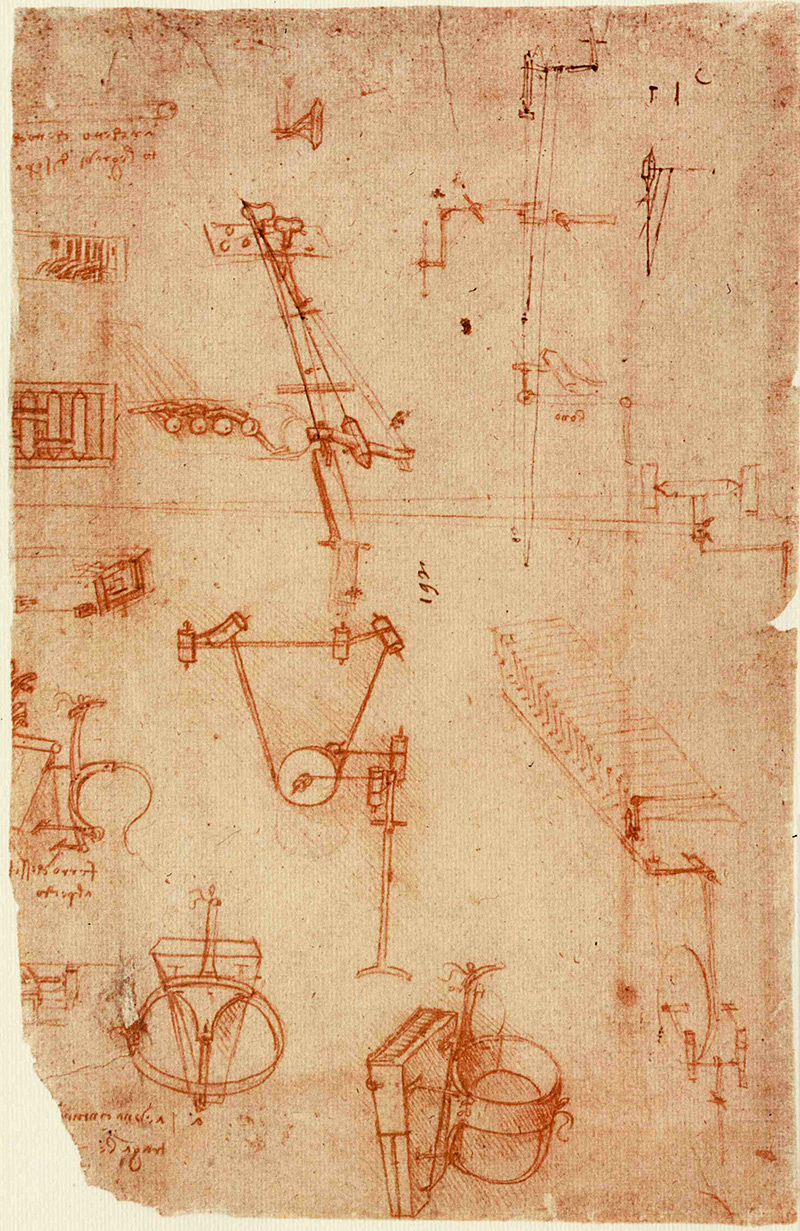

Sketched out in notebook pages contained in the Codex Atlanticus, the design showed “an outline of a construction concept for a bowed string instrument which at the same time is a keyboard instrument.” A violin that is also a piano, sort of…. Having built a version of the instrument 500 years after its invention, Polish concert pianist Slawomir Zubrzycki describes it as having “the characteristics of three [instruments] we know: the harpsichord, the organ and the viola da gamba.”

Zubrzycki spent four years working on his Viola Organista. A few years back, we featured a brief performance, his first public debut of the instrument in 2012. Now, we have much more audio of this incredible musical invention to share, including a longer performance from Zubrzycki at the top of the post, Marin Marais’ Suite in B Minor, performed in 2014 at the Copernicus Festival in Krakow. (You can see the full concert just above.) Despite these notable performances, and his notable creation, Zubrzycki is not the first to build a Viola Organista.

In 2011, Eduardo Paniagua, another musician devoted to Leonardo’s instrument—which does indeed sound like a “one person string ensemble,” as a commenter at this MetaFilter post noted—released a disc of 19 songs by Baroque composers, contemporaries of Leonardo, played on a Viola Organista built by Japanese maker Akio Obuchi. (Hear the full album on Spotify above.) Accompanying the album, writes Spanish site Musica Antigua (quoted in English here via Google translate), is “a profusely illustrated booklet with eleven of the organist viola prototypes that Leonardo himself devised,” with descriptions of the instrument’s operation by Paniagua.

Though Leonardo himself never built, nor heard, the instrument, it did attract interest not long after his death. “The oldest surviving model,” notes Musica Antigua, “is in El Escorial and is dated at the beginning of the seventeenth century.” Every version of the Viola Organista worked from original design specs like those in Leonardo’s hand above, using wheels to bow the strings when the keys are pressed, rather than hammers to strike them.

It’s an ingenious solution to a problem musicians had sought for many years to solve: creating a keyboard with rich dynamics and sustain. Whether Leonardo’s design is superior to other attempts, like the clavichord or, for that matter, the piano, I leave to musicologists to debate. We might all agree that the sound of his instrument, as played by Paniagua and Zubrzycki, is truly original and totally captivating.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness