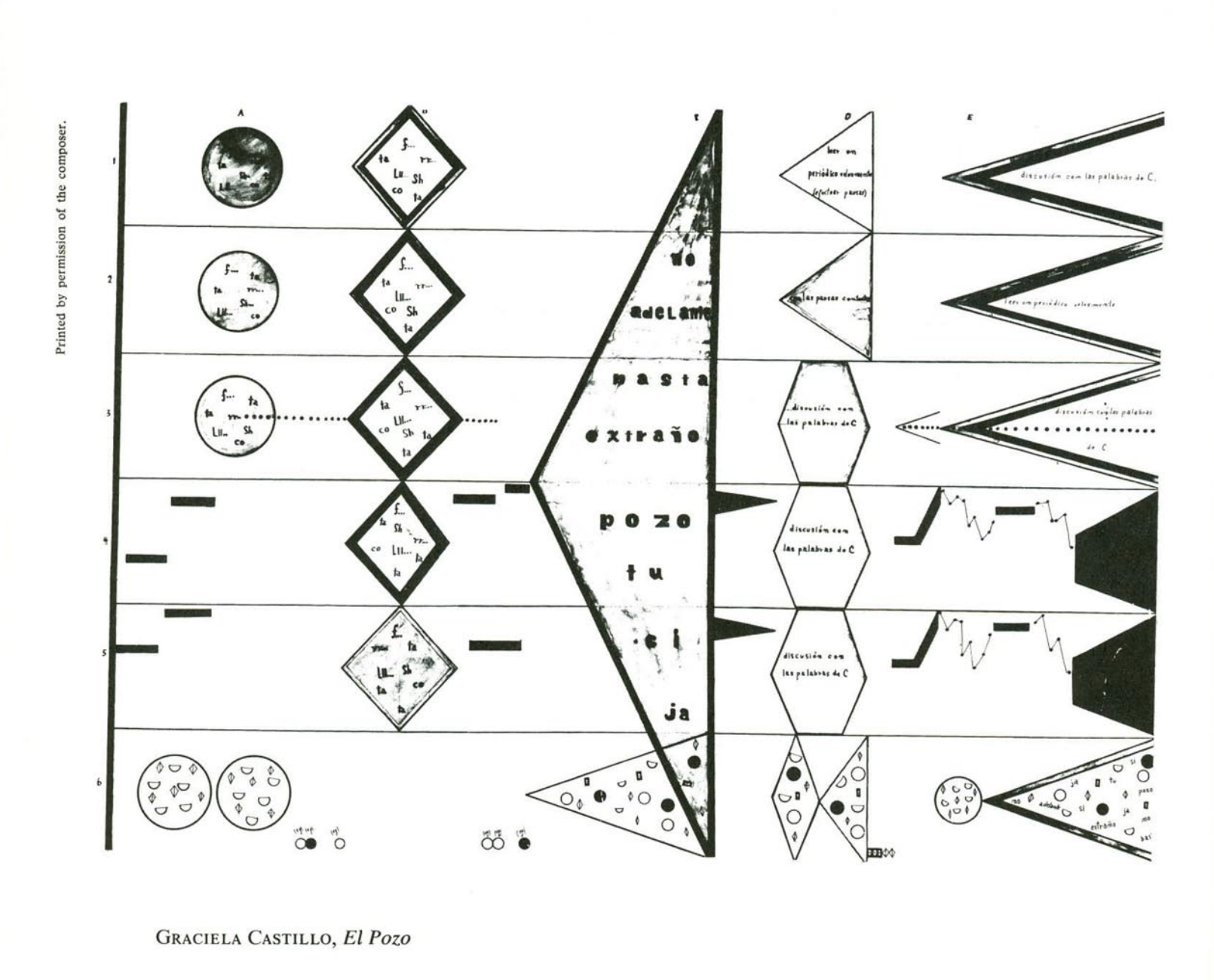

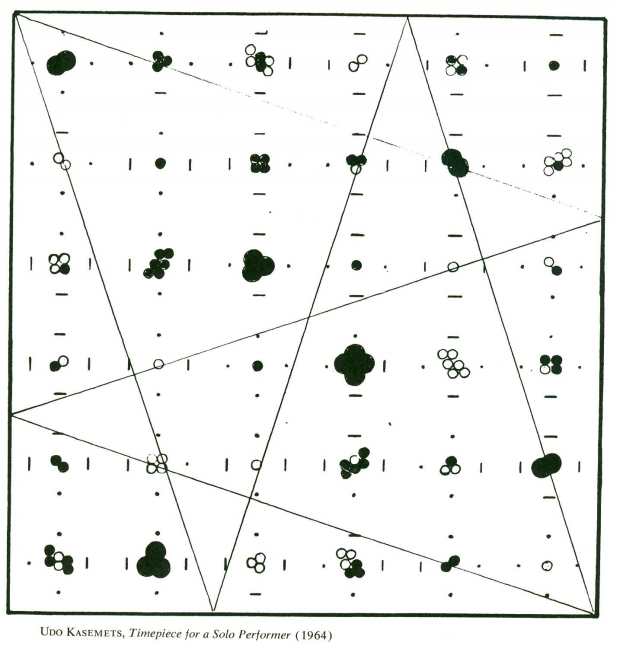

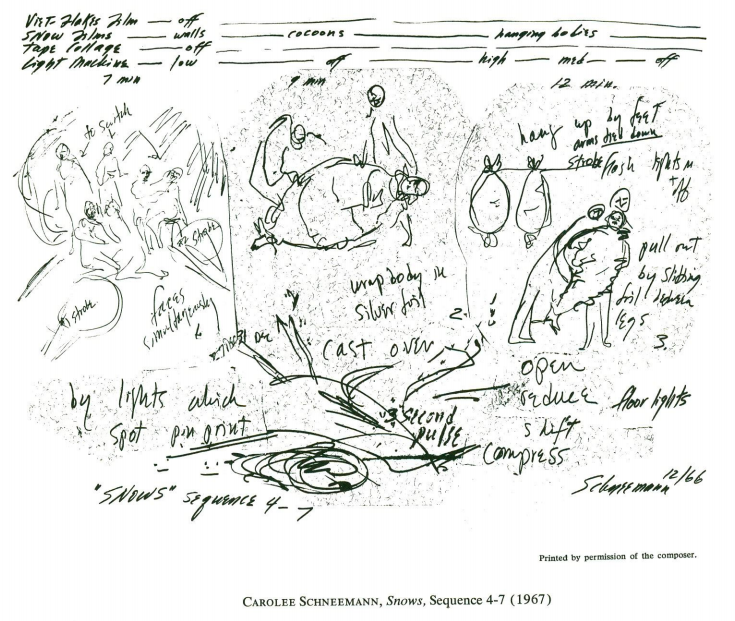

If you know just one piece by avant-garde composer and all-around oracle of indeterminacy John Cage, you know 1952’s 4′33″, which consists, for that length of time, of no deliberately played sounds at all. You’d think that if any piece could be played without a score, Cage’s signature composition could, but he did make sure to write one, and we featured it here on Open Culture a few years ago. Look at that score, of sorts, and you’ll sense that Cage had an interest not just in unconventional music, but in equally unconventional ways of notating that music. Hence the Notations project, Cage’s 1969 book collecting pieces of scores by 269 different composers and accompanying them with short texts.

Assembling the book from materials archived at the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Cage did include a page of one of his own scores, though not that of 4′33″ but of Music of Changes, a piano piece he’d composed the year before it for his friend David Tudor.

Tudor, a pianist as well as a composer of experimental music in his own right, also gets a page in Notations from his 1958 work Solo for Piano (Cage) for Indeterminacy. Lest this sound like a too-neat structure of reciprocity, rest assured that in the composition of the book’s text, as Cage explains in the book’s introduction, indeterminacy ruled, with “a process employing I‑Ching chance operations” dictating the number of words to be written, about which scores, and in what size and typeface as well.

Notations, which also includes scores from the Beatles, Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, Charles Ives (from whose archive Cage picked a blank piece of song paper), Gyorgy Ligeti, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Steve Reich, Igor Stravinsky, Toru Takemitsu, and many others, inspired a more recent follow-up project called Notations 21, which you can learn about in the video just below. A collaboration between musicologist and composer Theresa Sauer and designer Mike Perry, that 2009 book collects more than a hundred pieces of creative notation from some of the composers featured in Cage’s original, but also many who weren’t composing or indeed even alive in his day.

Notations 21 stands as a testament to Cage’s enduring influence as not just a composer but as the promoter of a worldview all about harnessing the forces of chance to enrich our lives, and to put us in a clearer frame of mind to see what comes next. “Musical notation is one of the most amazing picture-language inventions of the human animal,” Ross Lee Finney writes in the text of the original Notations. “It didn’t come into being of a moment but is the result of centuries of experimentation. It has never been quite satisfactory for the composer’s purposes and therefore the experiment continues.”

Related Content:

The Curious Score for John Cage’s “Silent” Zen Composition 4’33”

The Genius of J.S. Bach’s “Crab Canon” Visualized on a Möbius Strip

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.