Who hasn’t pinned one of Saul Bass’s elegant film posters on their wall—with either thumbtacks above the dormroom bed or in frame and glass in grown-up environs? Or maybe it’s 70s kitsch you prefer—the art of the grindhouse and sensationalist drive-in exploitation film? Or 20s silent avant-garde, the cool noir of the 30s and 40s, 50s B‑grade sci-fi, 60s psychedelia and French new wave, or 80s popcorn flicks…? Whatever kind of cinema grabs your attention probably first grabbed your attention through the design of the movie poster, a genre that gets its due in novelty shops and specialist exhibitions, but often goes unheralded in popular conceptions of art.

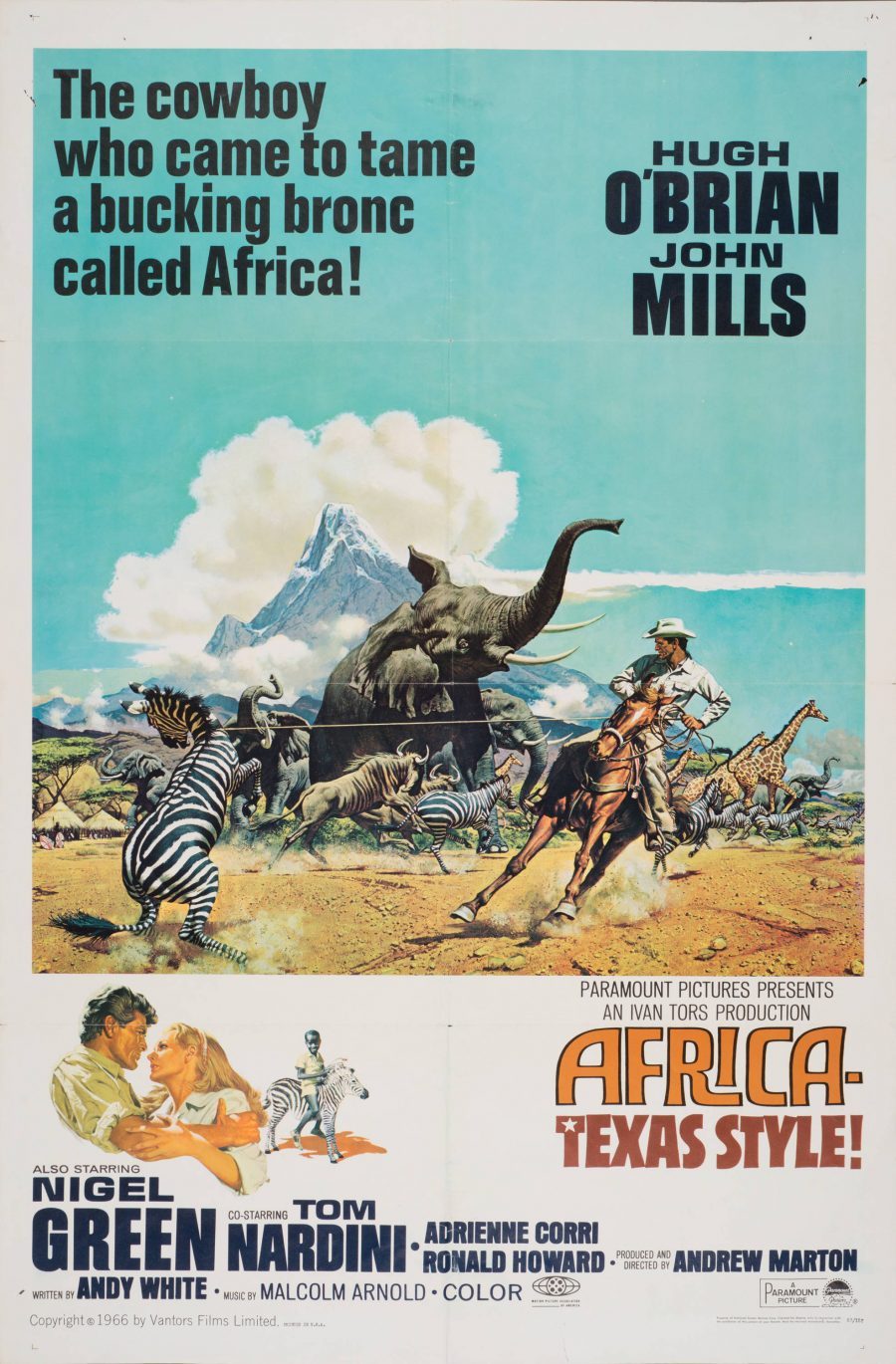

Despite its utilitarian and unabashedly commercial function, the movie poster can just as well be a work of art as any other form. Failing that, movie posters are at least always essential archival artifacts, snapshots of the weird collective unconscious of mass culture: from Saul and Elaine Bass’s minimalist poster for West Side Story (1961), “with its bright orange-red background over the title with a silhouette of a fire escape with dancers” to more complex tableaux, like the baldly neo-imperialist Africa Texas Style! (1967), “which features a realistic image of the protagonist on a horse, lassoing a zebra in front of a stampede of wildebeest, elephants, and giraffes.”

These two descriptions only hint at the range of posters archived at the University of Texas Harry Ransom Center—upwards of 10,000 in all, “from when the film industry was just beginning to compete with vaudeville acts in the 1920s to the rise of the modern megaplex and drive-in theaters in the 1970s.” So writes Erin Willard in the Ransom Center’s announcement of the digitization of its massive collection, expected to reach completion in 2019. So far, around 4,000 posters have been photographed and are becoming available online, downloadable in “Large,” “Extra Large,” and “High-Quality” resolutions.

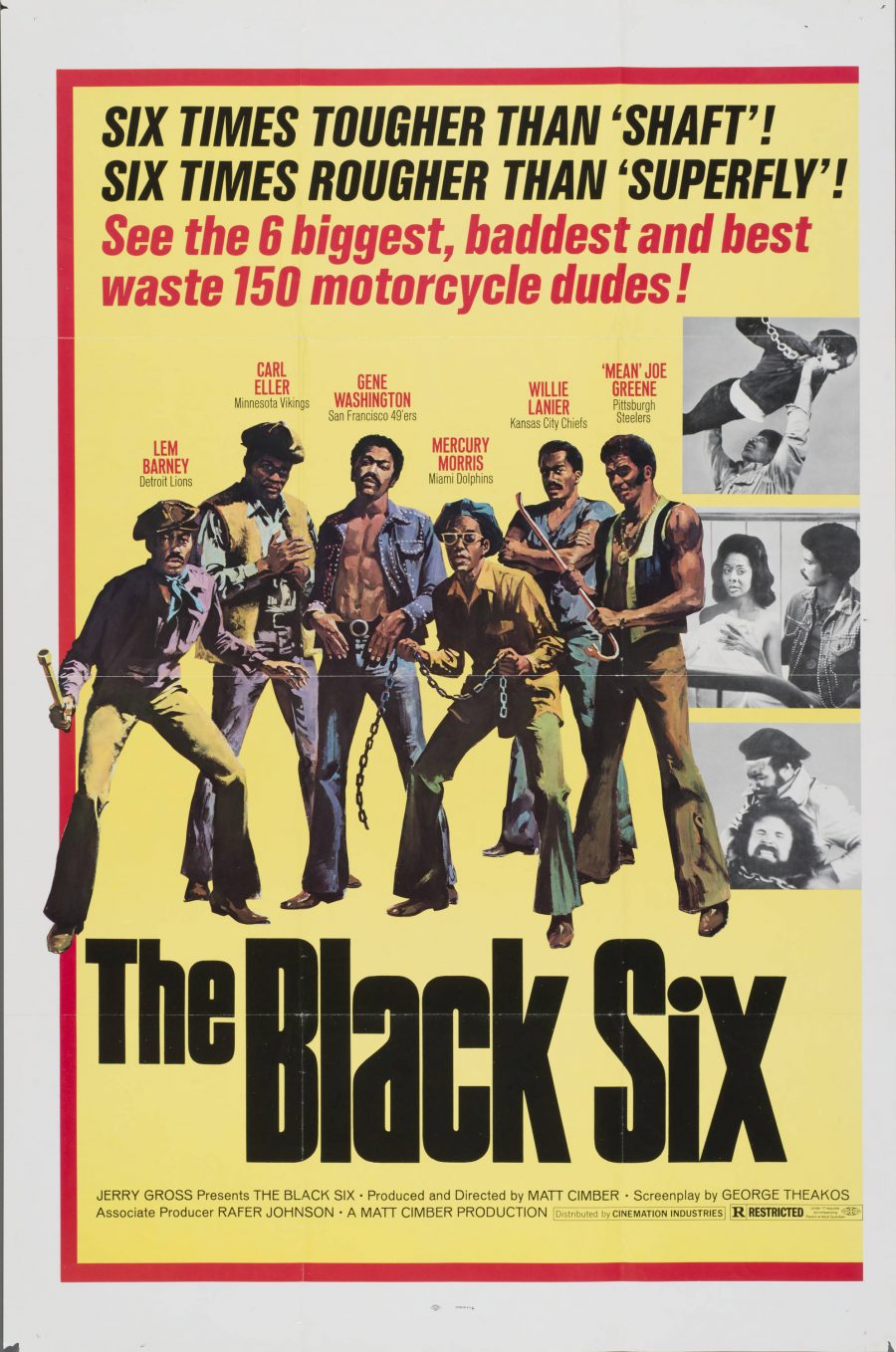

The bulk of the collection comes from the Interstate Theater Circuit—a chain that, at one time, “consisted of almost every movie theater in Texas”—and encompasses not only posters but film stills, lobby cards, and press books from “the 1940s through the 1970s with a particular strength in the films of the 1950s and 60s, including musicals, epics, westerns, sword and sandal, horror, and counter culture films.” Other individual collectors have made sizable donations of their posters to the center, and the result is a tour of the many spectacles available to the mid-century American mind: lurid, violent excesses, maudlin moralizing, bizarre erotic fantasies, dime-store adolescent adventures.…

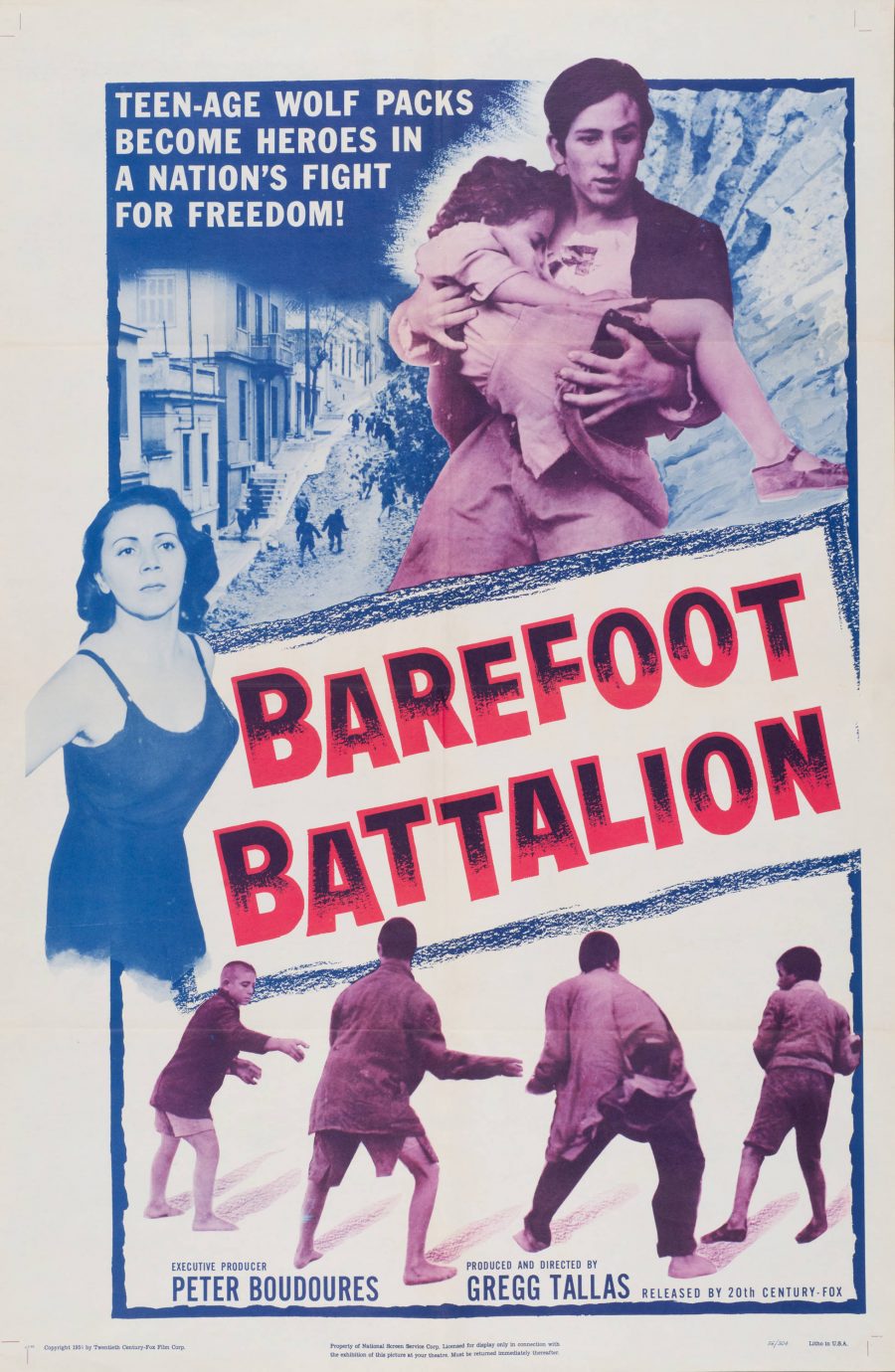

Some of the films are well-known examples from the period; most of them are not, and therein lies the thrill of browsing this online repository, discovering obscure oddities like the 1956 film Barefoot Battalion, in which “teen-age wolf packs become heroes in a nation’s fight for freedom!” The number of quirks and kinks on display offer us a prurient view of a decade too often flatly characterized by its penchant for grey flannel suits. The Mad Men era was a period of institutional repression and rampant sexual harassment, not unlike our own time. It was also a laboratory for a libidinous anarchy that threatened to unleash the pent-up energy and cultural anxiety of millions of frustrated teenagers onto the world at large, as would happen in the decades to come.

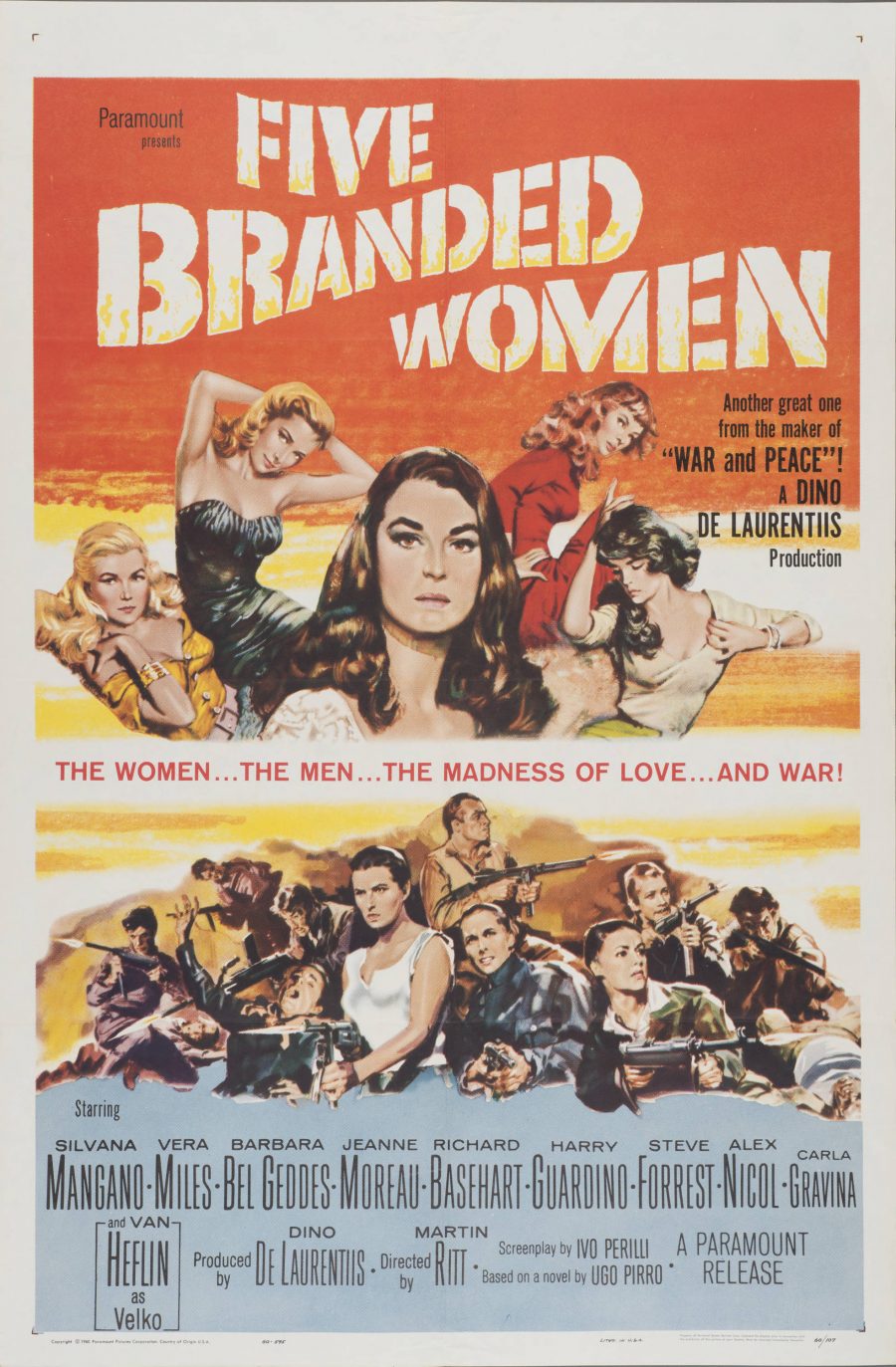

What we see in the marketing of films like Five Branded Women (1960) will vary widely depending on our orientations and political sensibilities. Is this cheap exploitation or an empowering precursor to Mad Max: Fury Road? Maybe both. For cultural theorists and film historians, these pulpy advertisements offer windows into the psyches of their audiences and the filmmakers and production companies who gave them what they supposedly wanted. For the ordinary film buff, the Ransom Center collection offers eye candy of all sorts, and if you happen to own a high-quality printer, the chance to hang posters on your wall that you probably won’t see anywhere else. Enter the online collection here.

Related Content:

The Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde

A Look Inside Martin Scorsese’s Vintage Movie Poster Collection

40 Years of Saul Bass’ Groundbreaking Title Sequences in One Compilation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness