The title of Walker Evans and James Agee’s extraordinary work of literary photojournalism, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, may have lost some of its ironic edge with subsequent acclaim and the fame of its writer and photographer. First begun in 1936 as a project documenting the largely invisible lives of white sharecropping families in rural Alabama, when the book appeared in print in 1941 it only sold about 600 copies. But over time, writes Malcolm Jones at Daily Beast, “it has established itself as a unique and enduring mashup of reporting, confession, and oracular prose.” As essential as Agee’s documentary prose poetics is to the book’s appeal, Evans’ photographs, like those of his many Depression-era contemporaries, have served as models for generations of photographers in decades hence.

Evans “photographs are not illustrative,” wrote Agee in the Preface. “They, and the text, are coequal, mutually independent, and fully collaborative.” If “the text was written with reading aloud in mind,” and Agee wanted us to hear, not simply see the language, perhaps we are also meant to see the individuals Evans captured, rather than just gaze at weathered faces and battered clothing, and view their bearers collectively as forlorn objects of pity.

Moreover, we shouldn’t look at these individuals only as members of a particular national group. In the book’s first paragraph, Agee writes:

The world is our home. It is also the home of many, many other children, some of whom live in far-away lands. They are our world brothers and sisters….

We are meant to see the subjects of Evans’ photographs and Agee’s exquisite descriptions as distinctive parts who make up the whole of humanity—or, more precisely, the world’s laboring people. Agee opens with a famous epigraph from The Communist Manifesto: “Workers of the world, unite and fight. You have nothing to lose but your chains, and a world to win.” (With a canny qualifying footnote explaining these words and their author as potentially “the property of any political party, faith, or faction”).

Several photographers employed, like Evans, by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression shared these sensibilities. The sympathies of Dorothea Lange, for example, lay with working people, not with the noblesse oblige of middle-class audiences who might support relief efforts but who had little desire to mingle with the great American unwashed. Many viewers—disconnected from rural life—stared at the photographs, writes Carrie Melissa Jones, “in issues of the now-defunct Life magazine, Time, Fortune, Forbes, and more,” and “took a paternalistic view of the south, asking: ‘How do we save them from themselves?’”

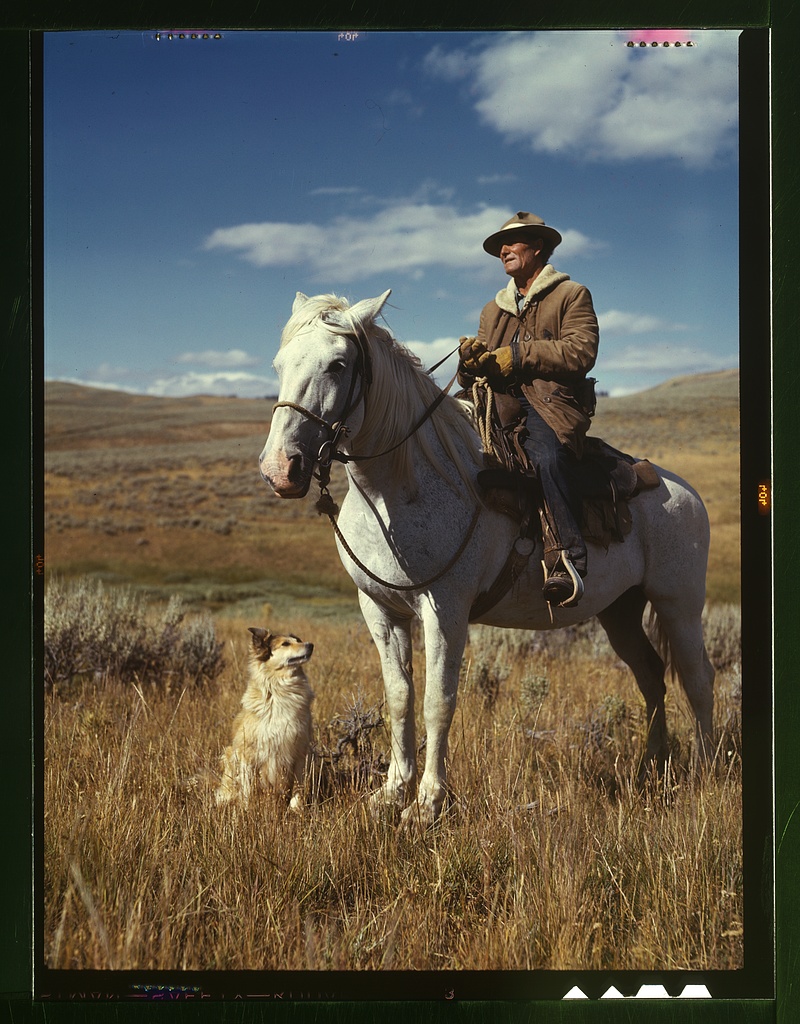

Can viewers of Depression-era photographs today put aside their implicit or explicit sense of moral superiority? Perhaps seeing photos of the era in color brings their subjects more immediacy and vividness, and you can see them by the hundreds at the Library of Congress’s online collection of work commissioned by the federal government during the Depression and World War II. Evans himself may have thought color photography “garish” and “vulgar,” Jordan G. Teicher notes at Slate (though Evans began taking his own color images in 1946). But contemporaries like Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, and John Vachon proved him wrong.

At the top of the post, see two photos from Lee—of two homesteaders in New Mexico (1940) and a shepherd with his horse and dog in Montana (1942). Beneath that, we have Wolcott’s striking photo of a rural cabin somewhere “in Southern U.S.,” circa 1940. Further up, see Delano’s image of sharecroppers chopping cotton in White Plains, Georgia (1941), which resembles the heroic figures in a Diego Rivera mural. And just above we have John Vachon’s image of rural school children in San Augustine County, Texas (1943). As we scan these faces and places, we might consider again Agee’s preface: “The governing instrument—which is also one of the centers of the subject—is individual, anti-authoritative human consciousness.” His instructions invite us to both empathy for each person we see and to broad human sympathy for all of them.

Once the U.S. entered the war, many Farm Security Administration photographers were reassigned to make propaganda for the Office of War Information (and a few, like Lange, also received commissions to photograph the Japanese Internment Camps). The nature of documentary photography began to change, largely reflecting small town American industriousness and civic pride, rather than rural desperation and struggle. Images like Fenno Jacobs’ patriotic demonstration in Southington Connecticut (1942) above, are typical. Quaint rows of houses and storefronts dominate during the war years. We also find interesting images like that of the woman below working on a “Vengeance” dive bomber in Tennessee, taken by Alfred T. Palmer in 1943. Aside from the dated clothing and machinery, her photograph seems as fresh and compelling as the day it first appeared.

“In color,” writes Emory University’s Jesse Karlsberg, “these images present themselves as relevant to the present, rather than consigned to the past. By displaying the problems they depict—such as segregation, poverty, and environmental degradation—in a contemporary form, the images imply that such problems may continue to be critical today.” They are indeed critical today. And may become even more so. And one hopes that writers, photographers, and artists, though they will not do so under the aegis of New Deal agencies, can find ways to document what is happening as they did decades ago. Such work carries global significance. And, as a recent Taschen book that collects New Deal photography from 1935 to 1943 describes it, photographs like those you see here “introduced America to Americans.” They also introduced Americans—who have been as divided in the past as they are today—to each other.

Related Content:

Found: Lost Great Depression Photos Capturing Hard Times on Farms, and in Town

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness