In the first decade or so of the Soviet Union’s existence, “avant-garde experimenters emerged from obscurity to benefit from actual state sponsorship,” writes Harvard professor of Russian Literature Ainsley Morse. Their “aesthetic radicalism jibed nicely with political turmoil.” Among these artists were Futurists and Formalists, poets, painters, actors, directors, and many who fit into all of these categories. Most famous among them—the rakish romantic poet, writer, artist, actor, playwright, and filmmaker Vladimir Mayakovsky—had already achieved a great deal of notoriety by 1917. After the Revolution, he threw himself, “wholeheartedly” into creating playful, optimistic agitprop for the Party and “became a foghorn for socialism.”

At least at first. “In hindsight,” Morse laments, it’s hard to see the careers of these early Soviet artists “without wincing: all of these artists and writers getting cozy with the state machine that would shortly bring about their mental and physical destruction: imprisonment, exile, starvation, and suicide.” Sadly, the last of these was to be Mayakovsky’s fate; he killed himself in 1930, as Stalin’s paranoid totalitarianism began to gain strength. Yet throughout the 1920s, Mayakovsky was “driven by ideological commitment,” as well as “financial exigency,” writes Robert Bird at the University of Chicago’s “Adventures in the Soviet Imaginary.” The wildly imaginative and idealistic poet “transformed the popular media landscape of Russia” under Lenin.

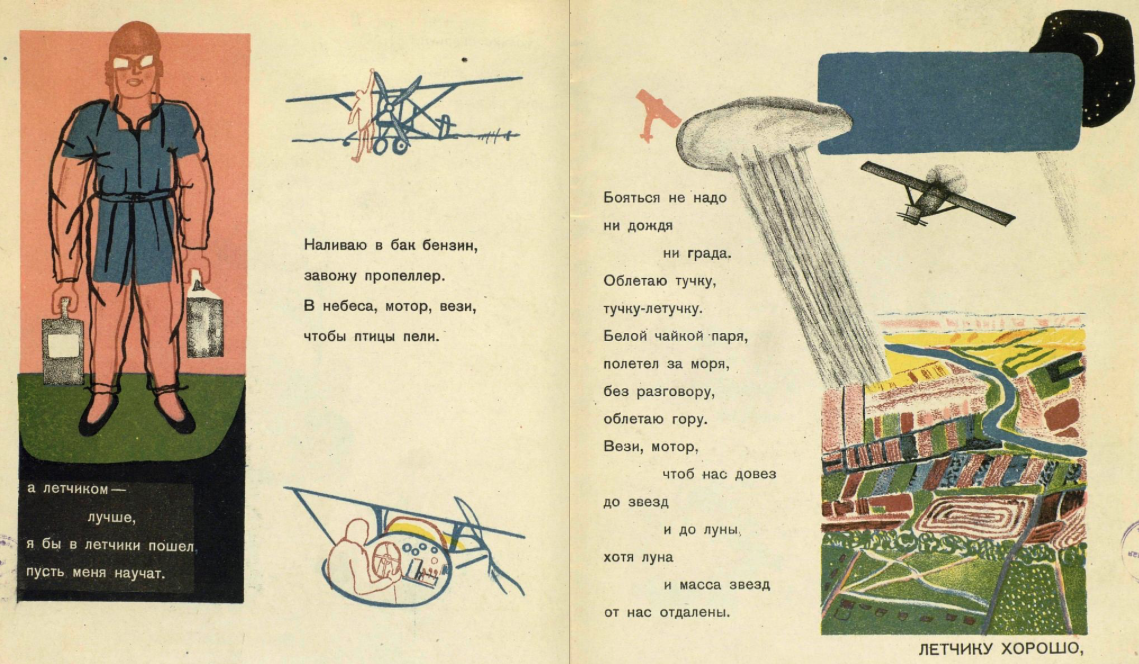

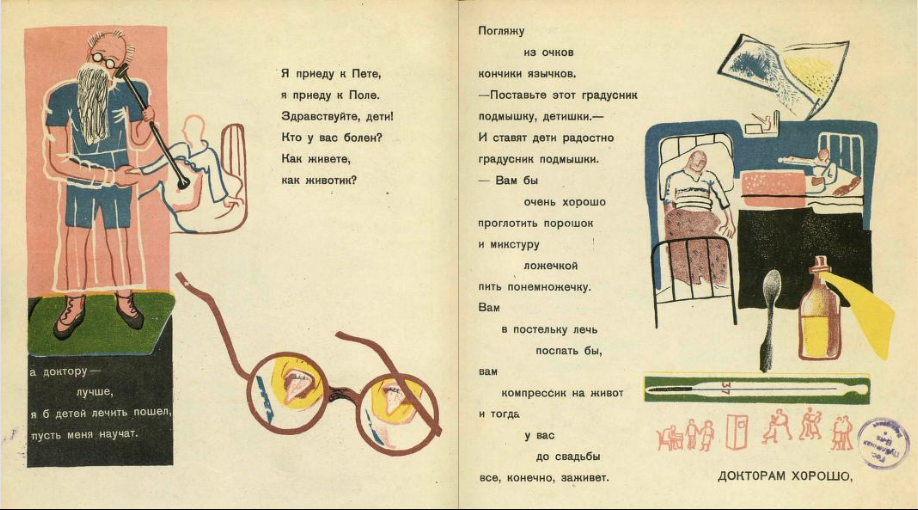

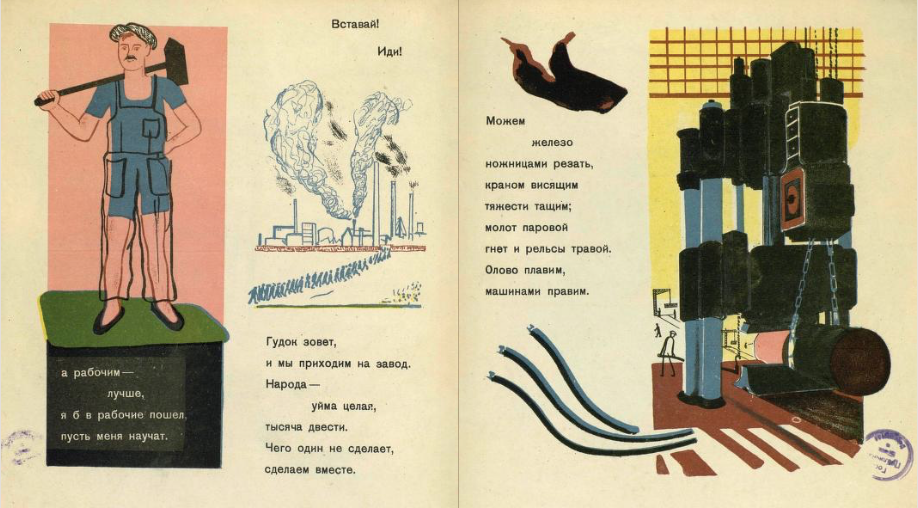

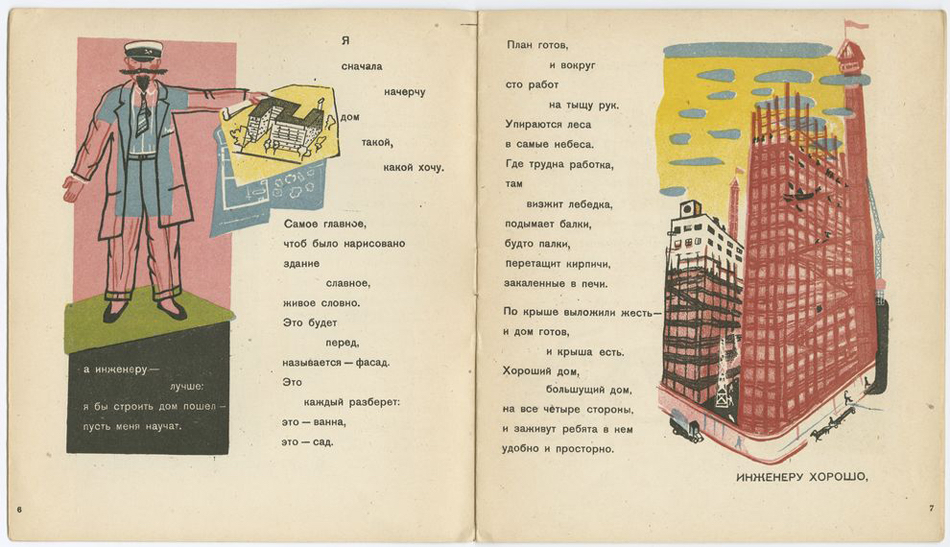

Though he was harshly criticized by other artists for his work as a propagandist, “under his pen Russian poetry began to speak with a more flexible and expressive (even anarchic) play of sound and rhythm.” Maykovsky applied his talents not only to posters and poetry for adults, but to works for children as well. “The early years of the Soviet Union were a golden age for children’s literature,” notes the New York Review of Books in their description of The Fire Horse, an early example of Soviet pedagogy from Mayakovsky and fellow poets Osip Mandelstam and Daniil Kharms. The pages you see here come from the first edition of another classic Mayakovsky children’s work—a long poem called Whom Shall I Be?, first published, with illustrations by Nisson Shifrin, in 1932, two years after the author’s death.

In these verses, Mayakovsky exhorts his readers to choose their own path, “create their own identities,” even as the book channels their desires “into specific existing roles” predetermined by a seemingly very limited number of professional choices (all for men). Nevertheless, in final lines of Whom Shall I Be? Mayakovsky writes, “All jobs are fine for you: / Choose / for your own taste!” The book illustrates what Ruxi Zhang calls the “ineffectiveness of Soviet pedagogy” in its earliest stages. Lenin and his even more iron-fisted successor desired a “generation of faithful workers.” Instead, children’s books like Mayakovsky’s “overplayed Soviet fantasy,” often advocating for “freedom that fundamentally countered Soviet expectations for children to follow directions from the regime without questioning or interpreting them.”

In Mayakovsky’s earlier children’s story, The Fire Horse, several craftsmen get together to make a beautiful toy horse—which cannot be bought at the store—for a young boy who dreams of being a cavalryman. The book, writes Morse, is “transparently didactic,” explaining “in detail how the horse is made, and at the cost of whose labor.” Nonetheless, its story sounds less like an exemplar from the state’s idea of a worker’s paradise and more like a vignette from anarchist, aristocrat, and naturalist Peter Kropotkin’s society of “mutual aid.” It’s only natural that Mayakovsky and his comrades’ children’s books would reflect their stylistic daring, individualism, and wit. “It wasn’t much of a leap” for Futurist artists whose “mainstay” had been artist’s books with “interdependent text and illustrations.” Eventually, however, avant-garde artists like Mayakovsky were purged or “tamed” by the new regime.

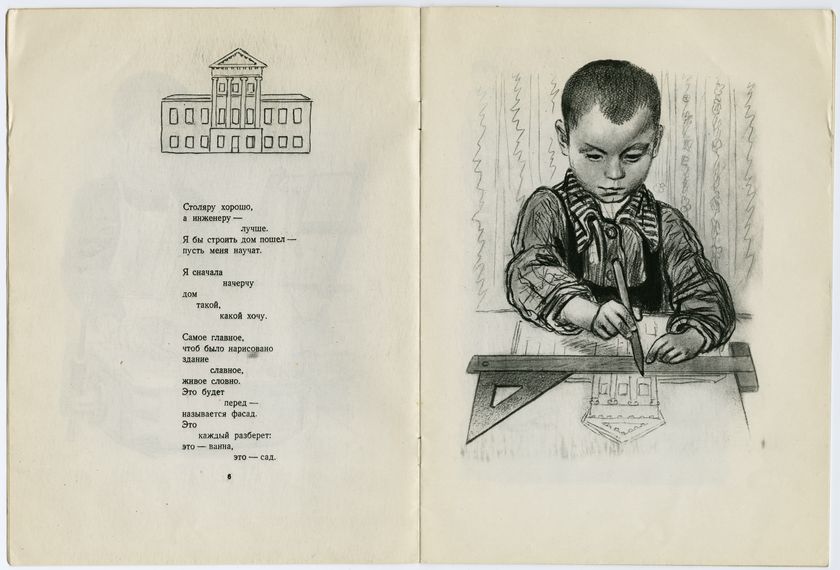

Bird demonstrates this with the pages below from a 1947 edition of Whom Should I Be? These correspond to the pages above from 1932, showing an engineer. In addition to the replacing of an enthusiastic adult worker with an obedient, dutiful child, “the abstract depictions of constructivist buildings are replaced by realistic renderings of neo-classical edifices.” In 1932, Socialist Realism had only just become the official style of the Soviet Union. By 1947, its absolute authority was mostly unquestionable. Browse (and read, if you read Russian) all of Mayakovsky’s Whom Should I Be? at the Internet Archive, or at the top of this post.

Related Content:

Hear Russian Futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky Read His Strange & Visceral Poetry

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness