We denizens of the craft-roasting, wi-fi-connected 21st century know well how to drink voluminous quantities of coffee and argue our opinions. In 17th-century London, however, such pursuits could look shocking and dangerous, especially since they happened in coffee houses, the new urban spaces where, according to Res Obscura’s Benjamin Breen, you could “bet on bear fights, warm your legs by the fire, witness public dissections (human and animal), solicit prostitutes (male and female), buy and sell stocks, purchase tulips or pornographic pamphlets, observe the activities of spies, dissidents, merchants, and swindlers, and then read your mail, delivered directly to your table.”

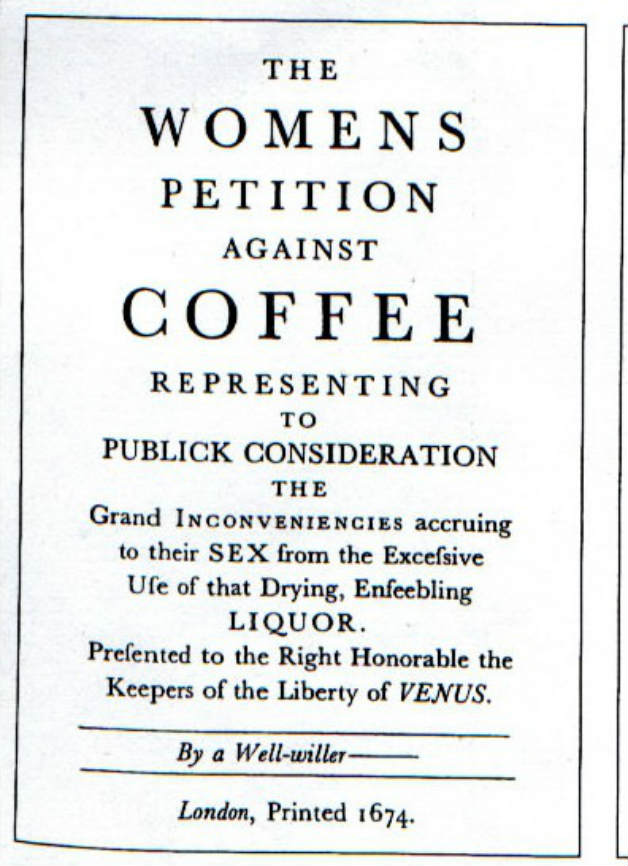

The patrons, while engaging in all that, partook of “a new drug from the Muslim world—black, odiferous, frightening, bewitching — called ‘coffee.’ ” Quickly finding itself subject to a great deal of scientific research and everyday argument as to its merits and demerits, the drink set off the satirical “Coffee Revolt of 1674,” which began that year with a pamphlet called “The Womens Petition Against Coffee,” purporting to offer “The Humble Petitions and Address of Several Thousands of Buxome Good-Women, Languishing in Extremity of Want.”

It seems that England, once “a Paradise for Women” thanks to “the brisk Activity of our men, who in former Ages were justly esteemed the Ablest Performers in Christendome,” had, for the non-coffee-drinking sex, become a deeply unsatisfying place:

The dull Lubbers want a Spur now, rather than a Bridle: being so far from dowing any works of Supererregation that we find them not capable of performing those Devoirs which their Duty, and our Expectations Exact. The Occasion of which Insufferable Disaster, after a furious Enquiry, and Discussion of the Point by the Learned of the Faculty, we can Attribute to nothing more than the Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE, which Riffling Nature of her Choicest Treasures, and Drying up the Radical Moisture, has so Eunucht our Husbands, and Cripple our more kind Gallants, that they are become as Impotent as Age, and as unfruitful as those Desarts whence that unhappy Berry is said to be brought.

Coffee, so insist the Buxome Good-Women, renders the men of England “as Lean as Famine, as Rivvel’d as Envy, or an old meager Hagg over-ridden by an Incubus. They come from it with nothing moist but their snotty Noses, nothing stiffe but their Joints, nor standing but their Ears.” These charges drew a response in the form of the “Mens Answer to the Womens Petition Against Coffee, Vindicating Their own Performances, and the Vertues of that Liquor, from the Undeserved Aspersions lately cast upon them by their SCANDALOUS PAMPHLET.” In it, the “men” ask the “women,” among other questions,

Why must innocent COFFEE be the object of your Spleen? That harmless and healing Liquor, which Indulgent Providence first sent amongst us, at a time when Brimmers of Rebellion, and Fanatick Zeal had intoxicated the Nation, and we wanted a Drink at once to make us Sober and Merry: ‘Tis not this incomparable settle Brain that shortens Natures Standard, or makes us less Active in the Sports of Venus, and we wonder you should take these Exceptions, since so many of the little Houses, with the Turkish Woman stradling on their Signs, are but Emblems of what is to be done within for your Conveniencies, meer Nurseries to promote the petulant Trade, and breed up a stock of hopeful Plants for the future service of the Republique, in the most thriving Mysteries of Debauchery; There being scarce a Coffee-Hut but affords a Tawdry Woman, a wonton Daughter, or a Buxome Maide, to accommodate Customers; and can you think that any which frequent such Discipline, can be wanting in their Pastures, or defective in their Arms?

“The extravagant claims for coffee made by men’s-health handbills exposed the commodity to satire,” writes Markman Ellis, author of The Coffee-House: A Cultural History, but “that coffee might have a deleterious effect on male virility was a theory accorded considerable scientific respect.” Still, pamphlets like the “Womens Petition” took as their target less the biological effects of coffee than “the new urban manners of masculine sociability that coffee represents. The satirist accuses coffee-house habitués of being ‘effeminate’ because they spend their time talking, reading, and pursuing their business rather than carousing, drinking, and whoring.” If any women of the 21st century would really prefer that men go back to those old ways — well, it would at least make for an interesting argument.

You can read online “The Womens Petition Against Coffee,” and “Mens Answer to the Womens Petition Against Coffee.”

For more background on the early days of coffee, see The Public Domain Review’s article, “The Lost World of the London Coffee House.”

Related Content:

“The Virtues of Coffee” Explained in 1690 Ad: The Cure for Lethargy, Scurvy, Dropsy, Gout & More

If Coffee Commercials Told the Unvarnished Truth

How Coffee Affects Your Brain: A Very Quick Primer

A Rollicking French Animation on the Perils of Drinking a Little Too Much Coffee

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.