When did you first hear David Sedaris? Normally in the case of a writer, let alone one of the most famous and successful writers alive, the question would be when you first read him, but Sedaris’ writing voice has never really existed apart from his actual voice. He first became famous in 1992 when National Public Radio aired his reading of the “Santaland Diaries,” a piece literally constructed from diaries kept while he worked in Santaland, the Christmas village at Macy’s, as an elf. Though that break illustrates the importance of what we might call two pillars of Sedaris’ writing process, nobody in his enormous fanbase-to-be gave it much thought at the time — they just wanted to hear more of his hilarious storytelling.

A quarter-century later, Sedaris has released more diaries — many more diaries — to his adoring public in the form of Theft by Finding, a hefty volume of selected entries written between 1977 and 2002. They give additional insight into not just the events and characters involved in the personal essays compiled in bestselling books like Naked, Me Talk Pretty One Day, and Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, but also into his writing process itself. “A woman on All Things Considered wrote a book of advice called If You Want to Write and mentioned the importance of keeping a diary,” a 26-year-old Sedaris writes in an entry from 1983. “After a while you’d stop being forced and pretentious and become honest and unafraid of your thoughts.”

Obviously he didn’t need that advice at the time, since even then keeping a diary had already become the first pillar of the David Sedaris writing process. “I started writing one afternoon when I was twenty, and ever since then I have written every day,” he once told the New Yorker, also a publisher of his stories. “At first I had to force myself. Then it became part of my identity, and I did it without thinking.” Most of what he writes in his diary each and every morning he describes as “just whining,” but “every so often there’ll be something I can use later: a joke, a description, a quote.”

The entries later cohere, along with other ideas and experiences, into his widely read stories. One such piece began, Sedaris told Fast Company’s Kristin Hohenadel, as “a diary entry from a trip to Amsterdam. He met a college kid who told him he’d learned that the first person to reach the age of 200 had already been born.” Then, Sedaris said, “I speculated that the first person to reach the age of 200 would be my father. And then I attached it to something else that had been in my diary, that all my dad talks about is me getting a colonoscopy. So I connected the 200-year-old man to my father wanting me to get a colonoscopy, and that became the story.”

Only connect, as E.M. Forster said, but you do need material to connect in the first place. Hence the second pillar of the process: carrying a notebook. To the Missouri Review Sedaris described himself as less funny than observant, adding that “everybody’s got an eye for something. The only difference is that I carry around a notebook in my front pocket. I write everything down, and it helps me recall things,” especially for later inclusion in his diary. When he publicly opened his notebook at the request of a redditor while doing an AMA a few years ago, he found the words, “Illegal metal sharks… white skin classy… driver’s name is free Time… rats eat coconuts… beautiful place city, not beautiful…”

These cryptic lines, he explained, were “notes I wrote in the Mekong delta a few weeks ago. A Vietnamese woman was giving me a little tour, and this is what I jotted down in my notebook.” For instance, “I was asking about all the women whom I saw on motor scooters wearing opera gloves, and masks that covered everything but their eyes. And the driver told me they were trying to keep their skin white, because it’s just classier. Tan skin means you’re a farmer. So that’s something I remembered from our conversation, so when I transcribe my notebook into my diary, I added all of that.” And one day his readers may well see this fragment of life that caught his attention appear again, but as part of a coherent, polished narrative whole.

The better part of that polishing happens through the practice of reading, and revising, in front of an audience. “During his biannual multicity lecture tours, Sedaris says he routinely notices imperfections in the text simply through the act of reading aloud to other people,” writes Hohenadel. “He circles accidental rhymes or closely repeated words, or words that sound alike — like night and nightlife — in the same sentence, rewriting after each reading and trying out revisions during the next stop on his tour.” When a passage gets laughs from the audience, he pencils in a check mark beside it; when one gets coughs (which he likens to “a hammer driving a nail into your coffin”), he draws a skull. “On the page it seems like I’m trying too hard, and that’s one of the things I can usually catch when I’m reading out loud,” he says, whether his writing “sounds a little too obvious” or “like somebody who’s just straining for a laugh.”

Related Content:

20 Free Essays & Stories by David Sedaris: A Sampling of His Inimitable Humor

Be His Guest: David Sedaris at Home in Rural West Sussex, England

Ray Bradbury on Zen and the Art of Writing (1973)

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

John Updike’s Advice to Young Writers: ‘Reserve an Hour a Day’

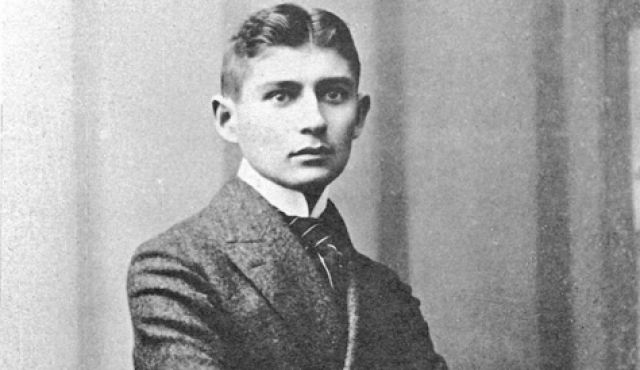

The Daily Habits of Famous Writers: Franz Kafka, Haruki Murakami, Stephen King & More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.