Browse through an archive of jazz writing from the last, oh, hundred years, and you’ll get the distinct impression that jazz, like the NFL, has been a man’s‑man’s‑man’s‑man’s world. “Of course,” writes Margaret Howze at NPR, “we have Billie, Ella, and Sarah,” and many other powerhouse female vocalists everyone knows and loves. These unforgettable voices seem to stand out as exceptions, and what’s more, “when we think of women in jazz, we automatically think of singers,” not instrumentalists.

Part of the marginalization of women in jazz has to do with the same kinds of cultural blind spots we find in discussions on every subject. We’ve been as guilty here as anyone of neglecting many great women in jazz, sadly. But women in jazz have also historically faced similar social barriers and stigmas as other women in all the arts. There are more than enough female vocalists, pianists, guitarists, trumpeters, drummers, saxophonists, bandleaders, teachers, producers to form a “worthy pantheon,” yet until fairly recently, a great many women jazz musicians have worked in the shadows of more famous men.

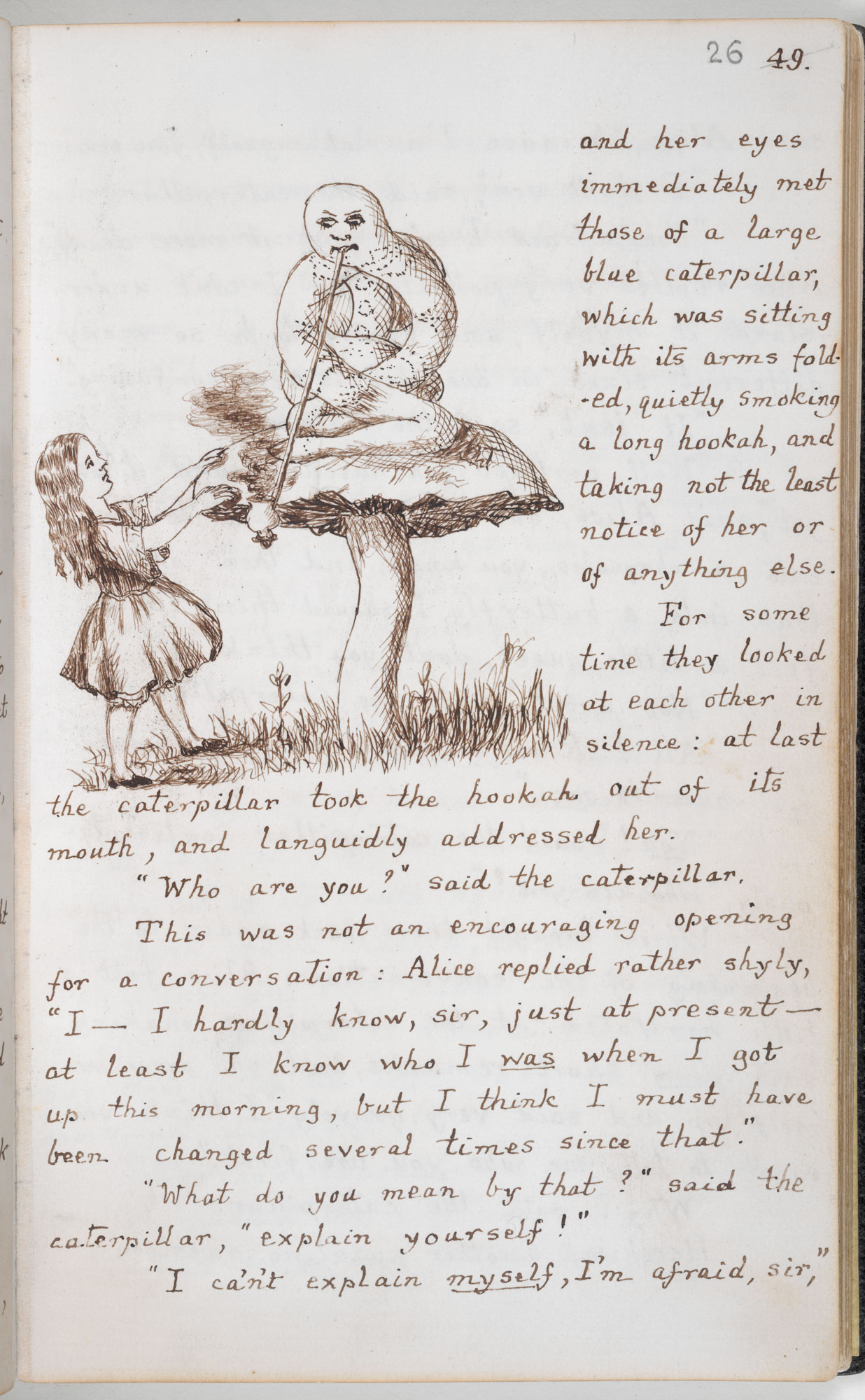

Howze’s two-part sketch of women in jazz offers a succinct chronological introduction, noting that “the piano, one of the earliest instruments that women played in jazz, allowed female artists” in the 20s and 30s “a degree of social acceptance.” In those years, “female instrumentalists usually formed all-women jazz bands or played in family-based groups.” One early standout musician, Dolly Hutchinson, née Jones, played the trumpet and cornet in bands all over the country. Hutchinson doesn’t appear in the Women of Jazz playlist below, but you can see her at the top in a clip from Oscar Michaux’s 1938 film Swing!

The Spotify playlist Women of Jazz does, however, offer samples from many other female jazz greats in its 91 tracks, from the very well-known—Nina Simone, Norah Jones, Diana Krall, “Billie, Ella, and Sarah”—to the very much overlooked. In that latter category falls a woman whose last name is familiar to us all. Lil Hardin Armstrong never achieved close to the degree of fame as her husband Louis, but the pianist, writes Howze, “helped shape Satchmo’s early career,” playing in “King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, a group Armstrong joined in 1922. He and Hardin began a romance and eventually married and it was Hardin who encouraged Armstrong to embark on a solo career.”

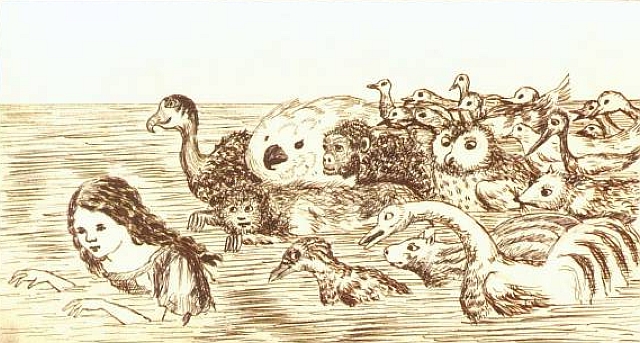

Hardin’s “Clip Joint,” featured in the playlist, showcases her sweet, clear contralto, distinguished by a tendency to wrap surprising hooks around the end of each line, pulling us forward to the next or keeping us hanging on for more. (Equally charming and effortlessly swinging, see her on the piano, above, accompanied by drummer Mae Barnes.) Another hugely influential woman in jazz, whose legacy “has also been somewhat occluded,” writes Alexa Peters at Paste, “by the legacy of her husband,” harpist and pianist Alice Coltrane deserves far more acclaim than she receives (at least in this writer’s humble opinion).

“An incredibly gifted avant-garde musician, composer, and arranger,” Coltrane’s solo compositions and her collaborations with saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, “are as sublime as they are indelibly important” to the development of spiritual jazz. Her incorporation of Hindustani instrumentation “like drones, ragas, Tabla drum, and sitar,” together with long hypnotic free jazz passages and the unusual choice of harp, contributed a new sonic vocabulary to the form.

Though hardly comprehensive, the Women of Jazz playlist does an excellent job of outlining a list of great female singers and instrumentalists throughout the history of jazz. As someone might point out, the compilation has its own blind spots. Though firmly rooted in the traditions of the American South, jazz has, since its golden age, been an international phenomenon. Yet the majority of the artists here are from the U.S. For a contemporary corrective, check out The Guardian’s list, “Five of the Best Young Female Jazz Musicians” from the U.K. and Scandinavia, or Afripop’s “Five South African Female Jazz Instrumentalists You Should Know,” or NPR’s list of four great “Latina Jazz Vocalists”.…

And we should not neglect to mention great French women in jazz. In the short film above on French jazz and trumpet duo Nelson Veras and Airelle Besson, the two musicians discuss their collaborative process. Any mention of gender would probably seem awkwardly irrelevant to the conversation. Perhaps all jazz talk should be like that. But it seems that first most jazz fans and writers need to spend some time getting caught up. We’ve got a wealth of resources above to get them started.

Related Content:

The History of Spiritual Jazz: Hear a Transcendent 12-Hour Mix Featuring John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Herbie Hancock & More

Hear 2,000 Recordings of the Most Essential Jazz Songs: A Huge Playlist for Your Jazz Education

1,000 Hours of Early Jazz Recordings Now Online: Archive Features Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington & Much More

Herbie Hancock to Teach His First Online Course on Jazz

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness