I well remember learning that Dr. Seuss’s real name was Theodor Geisel, mostly because I found Theodor Geisel was just as much fun to say as “Dr. Seuss.” Both names rolled around in the mouth, did somersaults and backflips off the tongue like the author’s multitude of strangely rubbery characters. With his Rube Goldberg machines, miniscule Whos, enormous Hortons, and mountains of comic absurdity, Seuss is like Swift for kids, his stories full of fantastic satire alongside much good clean common sense. Books like Horton Hears a Who and The Grinch Who Stole Christmas are chock full of “positive messages,” writes Amy Chyao at the Harvard Political Review, as well as trenchant social critique for five-year-olds.

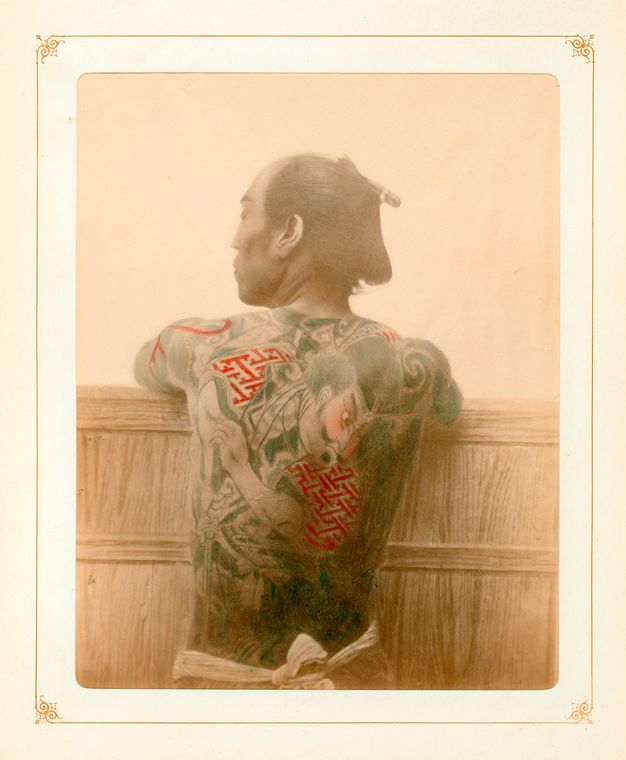

Among the many lessons, “embracing diversity is perhaps the single most salient one embedded in many of Dr. Seuss’s books.” Geisel did not always espouse this value. There are those who read Horton’s refrain, “a person’s a person no matter how small,” as penance for work he did as a political cartoonist during World War II, when he drew what Jonathan Crow described in a previous post as “breathtakingly racist” depictions of the Japanese, promoting the bigotry that led to violence and the internment of Japanese Americans, an action he vigorously supported.

You can see many of his political cartoons at UC San Diego’s digital library, “Dr. Seuss Went to War.” UCSD also hosts an online archive of Geisel’s advertising work, which sustained him throughout much of the 30s and 40s, and not all of which has aged well either.

Geisel later expressed regret for his blanket anti-Japanese attitudes after a trip to Japan in 1953. And he later made several anti-racist cartoons against Jim Crow laws and anti-Semitism. These might have been meant to atone for more of his less well-known work, advertisements featuring crude, ugly stereotypes of Africans and Arabs.

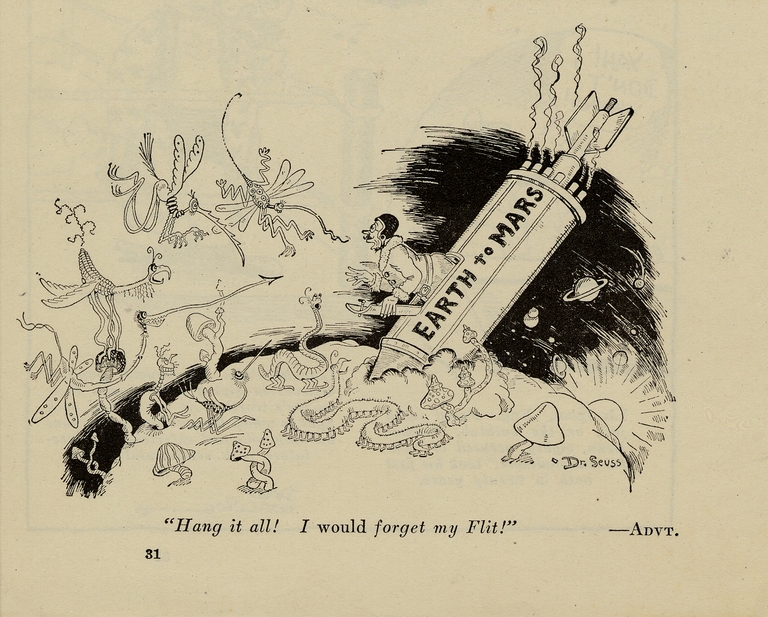

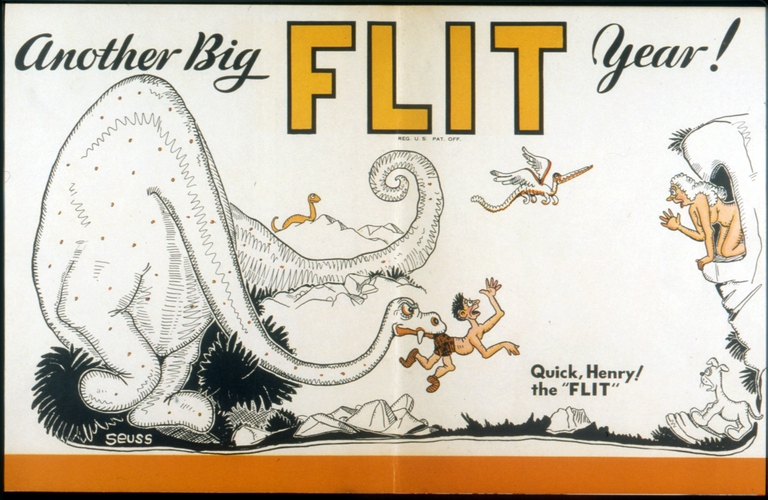

You will find some of these ads in the USCD archive; Geisel did truck in some blatantly inflammatory images. But he mostly drew innocuous, yet visually exciting, cartoons like the one at the top, one of the dozens of ads he drew during a 17-year campaign for Flit, an insect repellant made by Standard Oil.

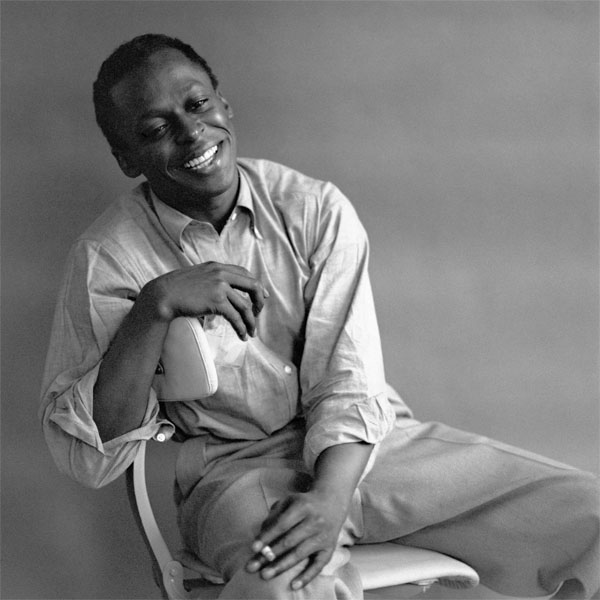

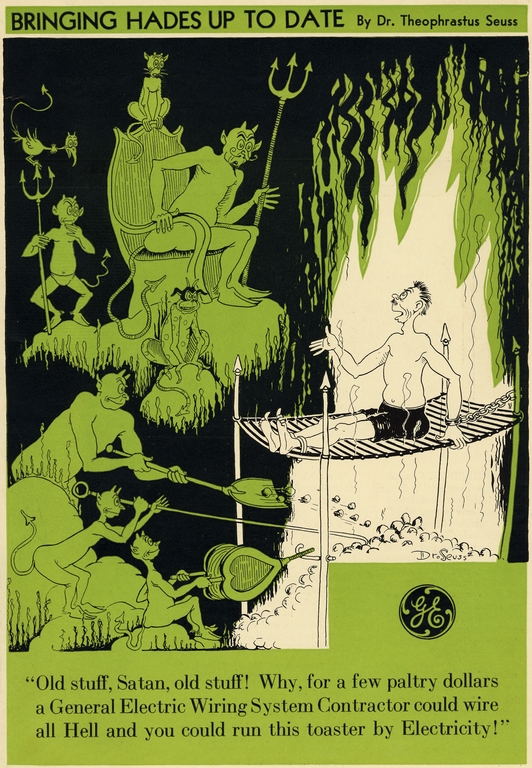

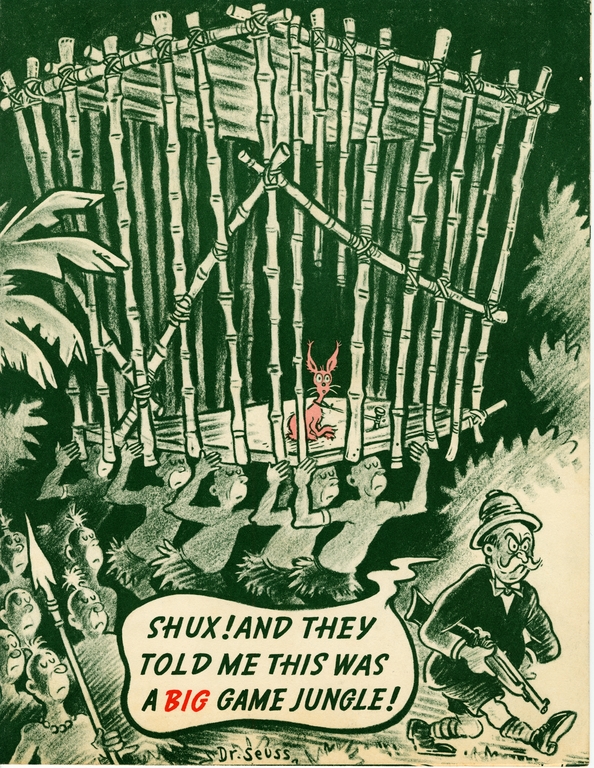

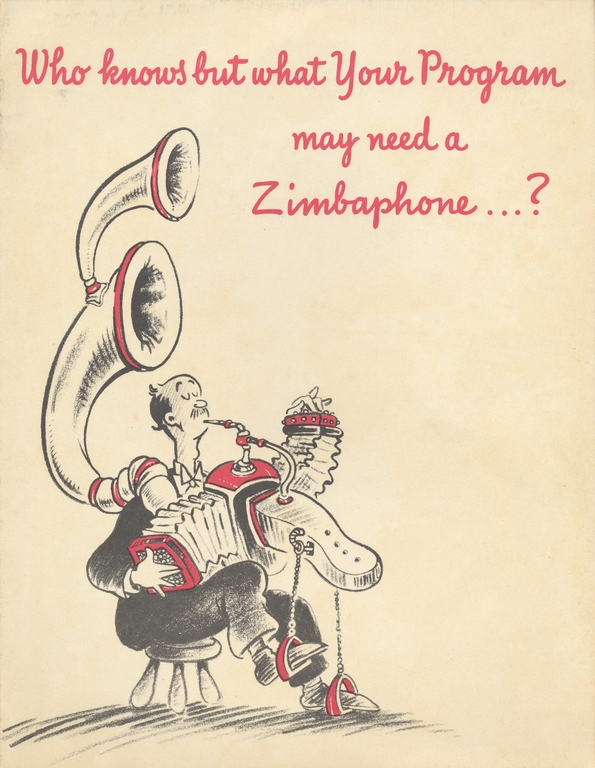

Geisel did ads for Standard Oil’s main product, promoting Essolube motor oil, further up, with the kind of creature that would later inhabit his children’s books. He got irreverently high concept with a GE ad set in hell, published explicitly under the pen name Dr. Theophrastus Seuss. And just above, in a brochure for the National Broadcasting Company, he introduces the visual aesthetic of Horton’s jungle, with a troupe of stereotypical grass-skirted Africans that might have come from one of Hergé’s offensive colonialist Tintin comics. (Both Seuss’s and Hergé’s early work are testaments to the common co-existence of progressive politics with often contemptuous or condescending treatment of nonwhite people in the early twentieth century.)

The Seuss advertisements archive shows us the artist’s development from visual puns and quirks to the fully-fledged mechanical surrealism of his mature style, as in the National Broadcasting Company brochure above, with its musical contraption the “Zimbaphone,” a precursor to the many cacophonous, overcomplicated instruments to come. It is when he is at his most inventive that Geisel is at his best. When he abandoned lazy, mean-spirited stereotypes, his work embraced a world of joyous possibility and weirdness.

Related Content:

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!

Dr. Seuss’ World War II Propaganda Films: Your Job in Germany (1945) and Our Job in Japan (1946)

Neil Gaiman Reads Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness