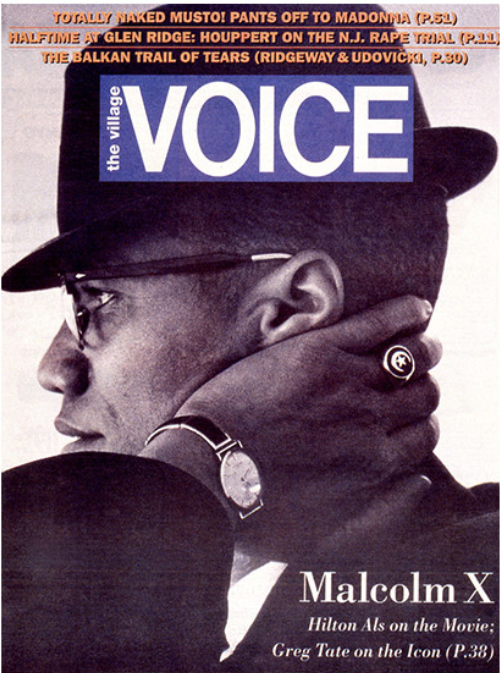

After The Village Voice announced this week that it was folding its print operation, a couple people compared the venerable NYC rag’s demise to the end of Gawker, the snarky online tabloid taken down by Hulk Hogan and his shadowy financier Peter Thiel. For too many reasons to list, this comparison seems to my mind hardly apt. There’s a gesture toward the Voice’s profane unruliness, but the alternative weekly, founded in 1955, transcended the blog age’s sophomoric nihilism. The hermetic container of its newsprint sealed out frothing comment sections; no links ferried readers through rivers of personalized algorithms.

The Voice published hard journalism that many, including Voice writers themselves, have ruefully revisited of late. Its music and culture writers like Nat Hentoff, Lester Bangs, Sasha Frere-Jones, Robert Christgau and so many others are some of the smartest in the business. Its columnists, editors, and reviewers—Andrew Sarris, J. Hoberman, Robert Sietsema, Tom Robbins, Greg Tate, Michael Musto, Thulani Davis, Ta-Nehisi Coates—equally so.

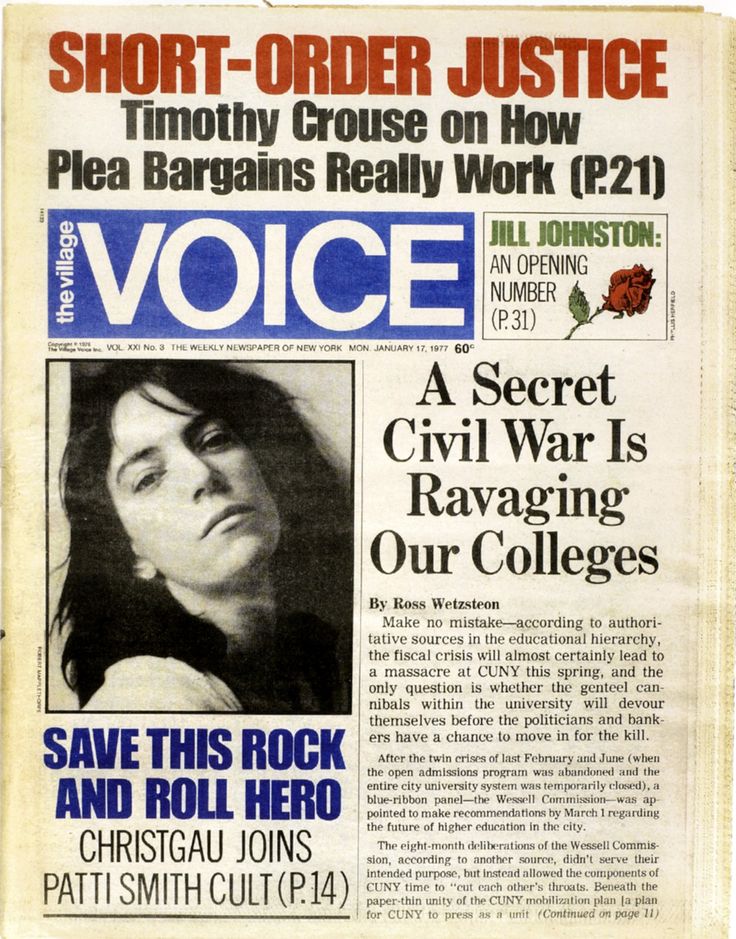

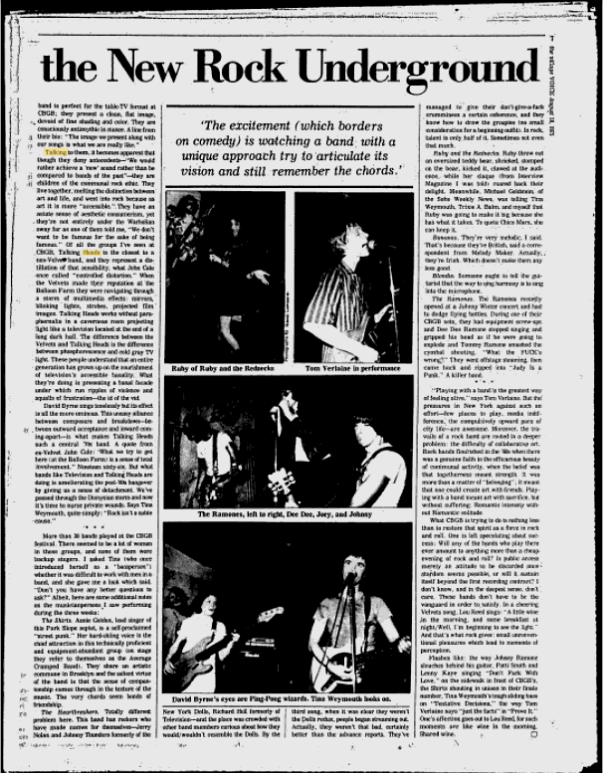

In its over sixty-year run, Voice writers sat in the front rows for the birth for hard bop, free jazz, punk, no wave, and hip-hop, and all manner of downtown experimentalism in-between and after.

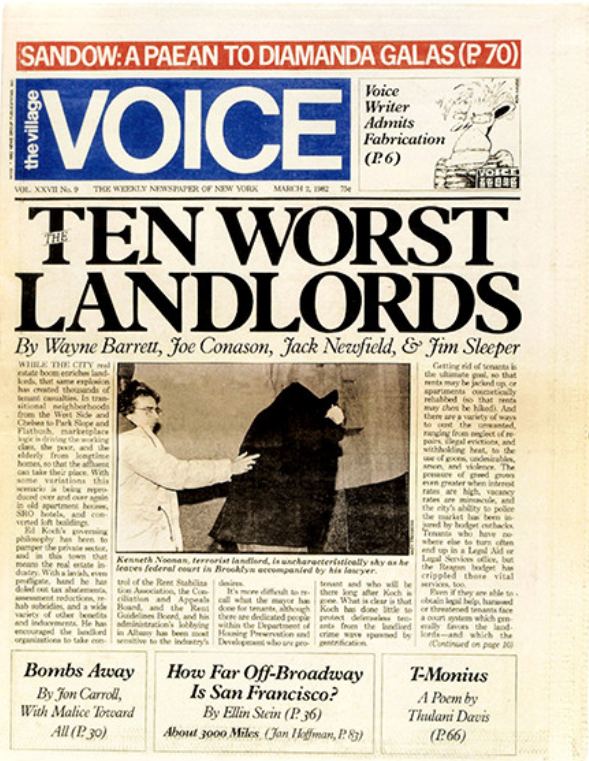

Amongst the many remembrances from current and former Voice staff in a recent Esquire oral history, one from editor and writer Camille Dodero stands out: “The alt-weekly’s purpose was, in theory, speaking truth to power and the ability to be irreverent, and print the word ‘fuck’ while doing so.’” Mission accomplished many times over, as you can see yourself in Google’s Village Voice archive, featuring 1,000 scanned issues going all the back to 1955, when Norman Mailer founded the paper with Ed Fancher, Dan Wolf, and John Wilcock. There are “blind spots” in Google’s archive of the Voice, noted John Cook at the erstwhile Gawker. In 2009, his “searches didn’t turn up any coverage of Norman Mailer’s 1969 campaign or the Stonewall riots… and there’s not much on Rudy Giuliani’s mayoral bid.” Many years later, months and years in the Google archive remain blank, “no editions available.”

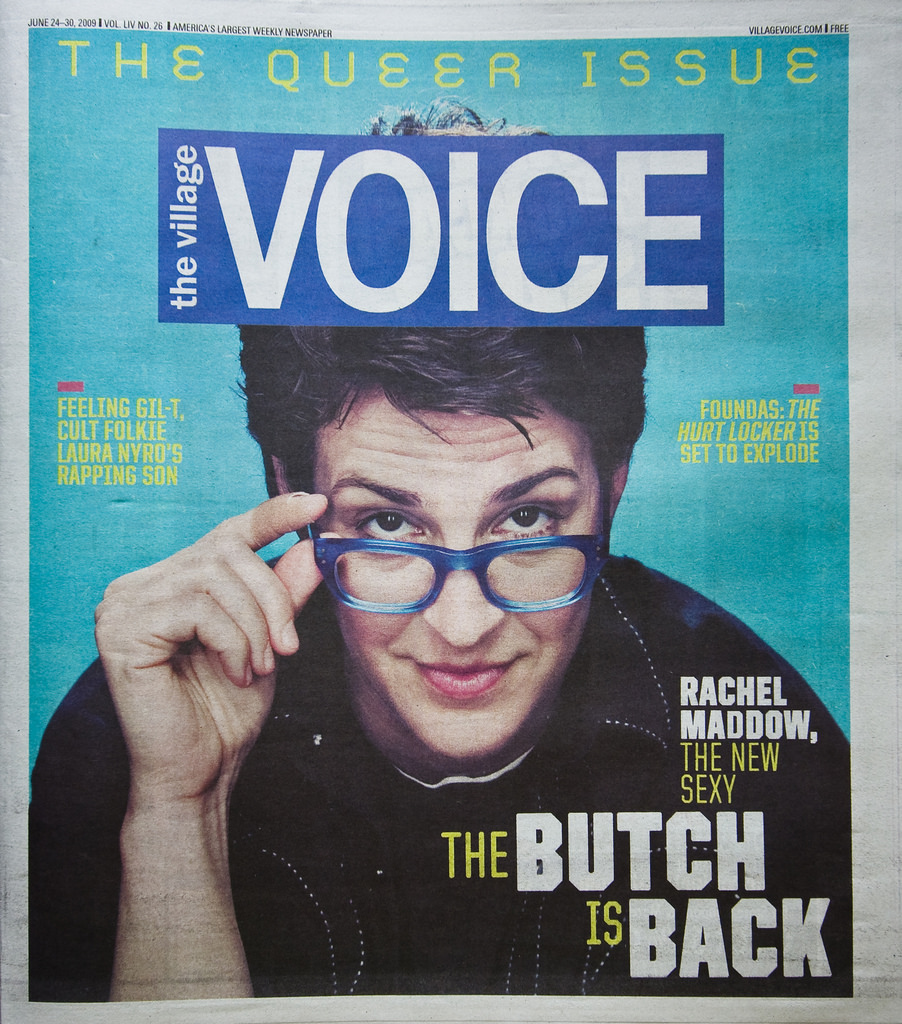

The Voice has had its own blind spots. Writer Walter Troy Spencer referred to Stonewall, for example, as “The Great Faggot Rebellion” and used a phrase that has perhaps become the most wearisome in American English: “there was mostly ugliness on both sides.” This anti-gay prejudice was a regular feature of the paper’s first few years, but by 1982, just as the AIDS crisis began to filter into public consciousness, the Voice was the second organization in the US to offer extended benefits to domestic partners. It became a prominent voice for New York’s LGBTQ culture and politics, through all the buyouts, cutbacks, and unbeatable competition that brought it to its current pass.

The paper also became a voice for the most interesting things happening in the city at any given time, such as the goings on at a Bowery dive called CBGB in 1975. Character studies have long been a Voice staple. Lester Bangs’ write-up of Iggy Pop two years later cut to the heart of the matter: “It’s as if someone writhing in torment has made that writhing into a kind of poetry.” Back in ’75, Andrew Sarris wrote a rather jaw-dropping profile of Hervé Villechaize (in which he begins a sentence, “The problem of midgets….”). …. the more I look through Voice back issues, the more I think it might have been a Gawker of its time, but as onetime columnist Harry Siegel tells Esquire, “what made it unique depends a lot on the age of who you’re asking. It was a very different paper in different decades. It was valuable enough for a long time that people paid money to read it.”

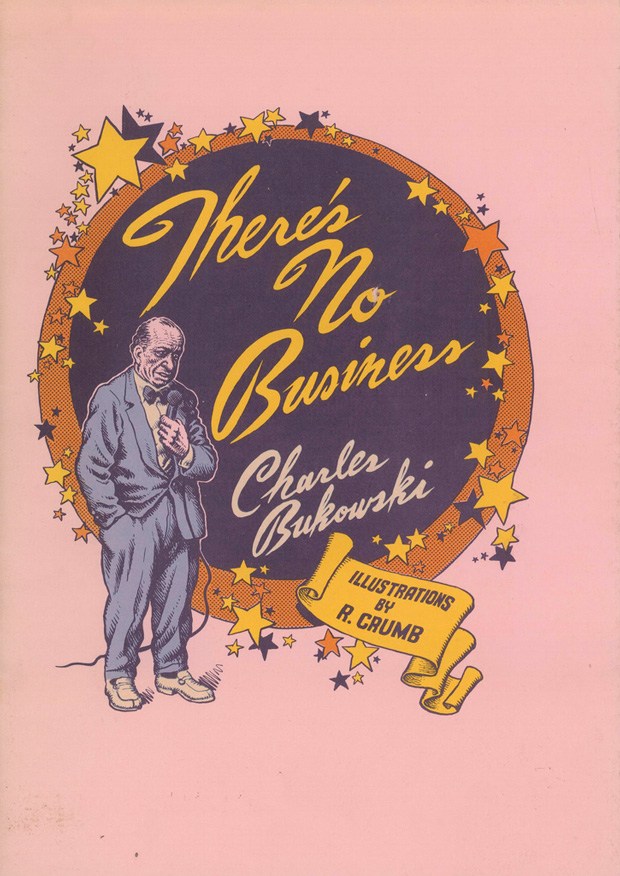

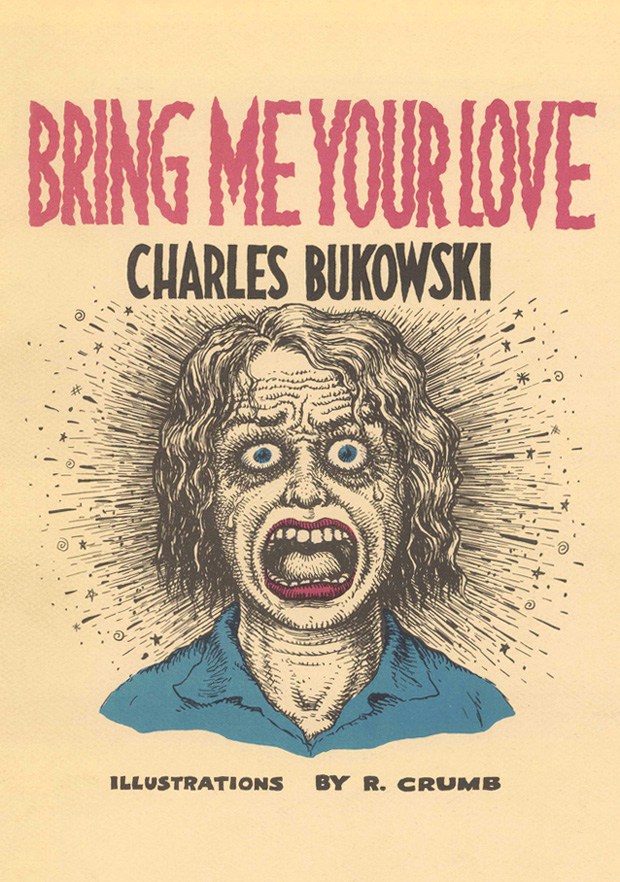

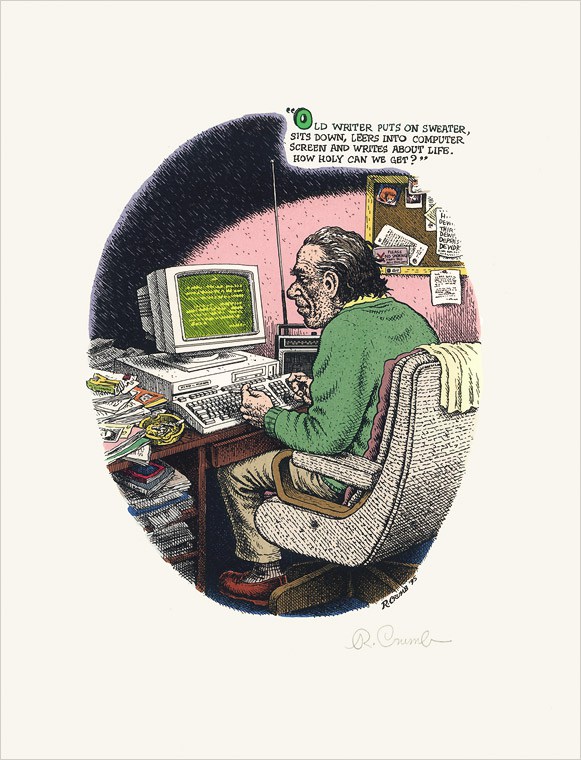

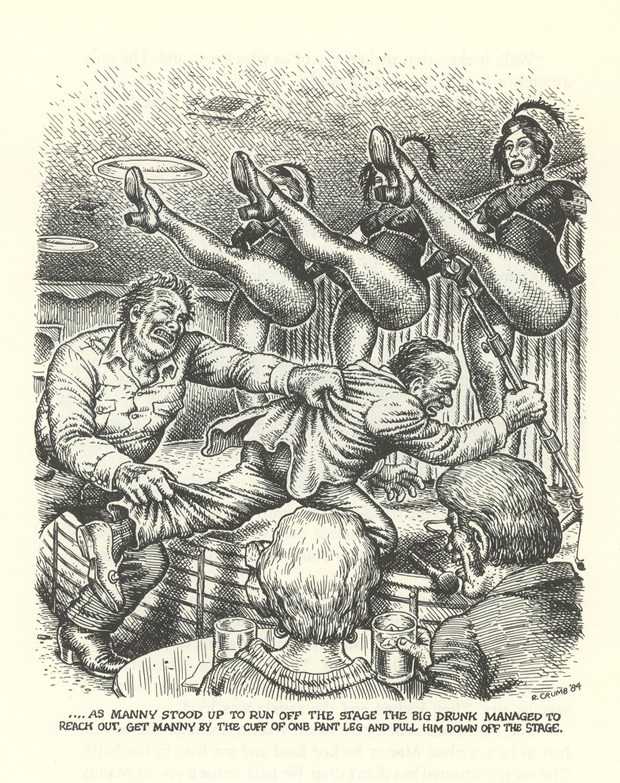

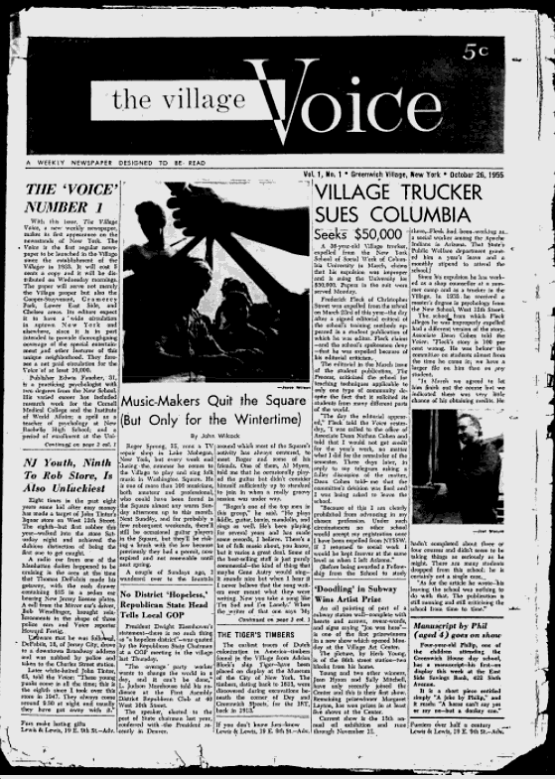

Indeed its first issue cost 5 cents, though by the nondescript cover, above, you wouldn’t guess it would amuse or titillate in the ways the Village Voice became well-known for—in its columns, photos, cartoons, and libertine advertising and classifieds. But most people these days remember it as “free every Wednesday,” to proffer dance, film, theater, music, restaurants, to line subway cars and birdcages, and to open up the city to its readers. The Voice is dead, long live the Voice.

Enter the digital archive of the Voice here.

Writings from the Voice have been collected in these anthologies: The Village Voice Anthology (1956–1980) and The Village Voice Reader.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness