One of the most propulsive forces in our social and economic lives is the rate at which emerging technology transforms every sphere of human labor. Despite the political leverage obtained by fearmongering about immigrants and foreigners, it’s the robots who are actually taking our jobs. It is happening, as former SEIU president Andy Stern warns in his book Raising the Floor, not in a generation or so, but right now, and exponentially in the next 10–15 years.

Self-driving cars and trucks will eliminate millions of jobs, not only for truckers and taxi (and Uber and Lyft) drivers, but for all of the people who provide goods and services for those drivers. AI will take over for thousands of coders and may even soon write articles like this one (warning us of its impending conquest). What to do? The current buzzword—or buzz-acronym—is UBI, which stands for “Universal Basic Income,” a scheme in which everyone would receive a basic wage from the government for doing nothing at all. UBI, its proponents argue, is the most effective way to mitigate the inevitably massive job losses ahead.

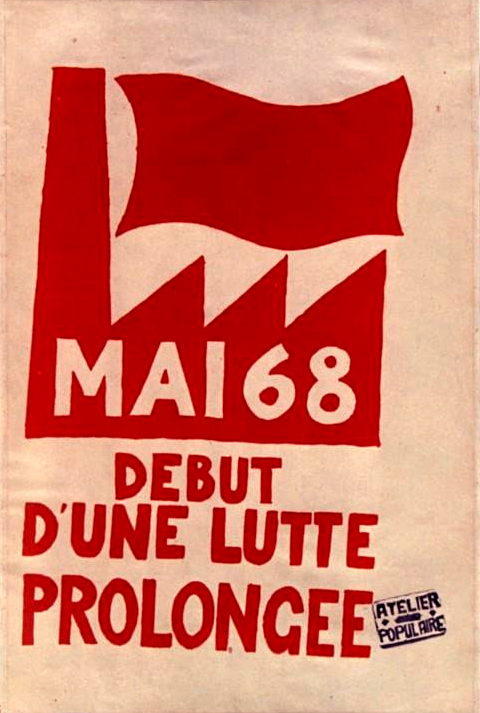

Those proponents include not only labor leaders like Stern, but entrepreneurs like Peter Barnes and Elon Musk (listen to him discuss it below), and political philosophers like Georgetown University’s Karl Widerquist. The idea is an old one; its modern articulation originated with Thomas Paine in his 1795 tract Agrarian Justice. But Thomas Paine did not foresee the robot angle. Alan Watts, on the other hand, knew precisely what lay ahead for post-industrial society back in the 1960s, as did many of his contemporaries.

The English Episcopal priest, lecturer, writer, and popularizer of Eastern religion and philosophy in England and the U.S. gave a talk in which he described “what happens when you introduce technology into production.” Technological innovation enables us to “produce enormous quantities of goods… but at the same time, you put people out of work.”

You can say, but it always creates more jobs, there’ll always be more jobs. Yes, but lots of them will be futile jobs. They will be jobs making every kind of frippery and unnecessary contraption, and one will also at the same time beguile the public into feeling that they need and want these completely unnecessary things that aren’t even beautiful.

Watts goes on to say that this “enormous amount of nonsense employment and busywork, bureaucratic and otherwise, has to be created in order to keep people working, because we believe as good Protestants that the devil finds work for idle hands to do.” People who aren’t forced into wage labor for the profit of others, or who don’t themselves seek to become profiteers, will be trouble for the state, or the church, or their family, friends, and neighbors. In such an ethos, the word “leisure” is a pejorative one.

So far, Watts’ insights are right in line with those of Bertrand Russell and Buckminster Fuller, whose critiques of meaningless work we covered in an earlier post. Russell, writes philosopher Gary Gutting, argued “that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” Harm to our intellects, bodies, creativity, scientific curiosity, environment. Watts also suggests that our fixation on jobs is a relic of a pre-technological age. The whole purpose of machinery, after all, he says, is to make drudgery unnecessary.

Those who lose their jobs—or who are forced to take low-paying service work to survive—now must live in greatly diminished circumstances and cannot afford the surplus of cheaply-produced consumer goods churned out by automated factories. This Neoliberal status quo is thoroughly, economically untenable. “The public has to be provided,” says Watts, “with the means of purchasing what the machines produce.” That is, if we insist on perpetuating economies of scaled-up production. The perpetuation of work, however, simply becomes a means of social control.

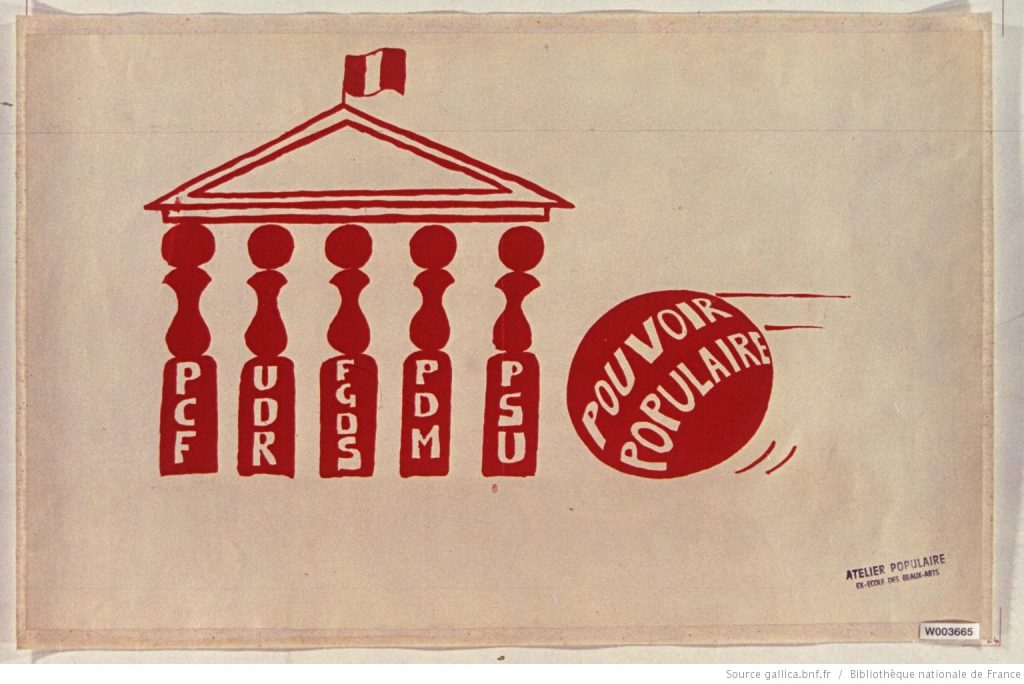

Watts has his own theories about how we would pay for a UBI, and every advocate since has varied the terms, depending on their level of policy expertise, theoretical bent, or political persuasion. It’s important to point out, however, that UBI has never been a partisan idea. It has been favored by civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King and controversial conservative writers like Charles Murray; by Keynesians and supply-siders alike. A version of UBI at one time found a proponent in Milton Friedman, as well as Richard Nixon, whose UBI proposal, Stern notes, “was passed twice by the House of Representatives.” (See Stern below discuss UBI and this history.)

During the sixties, a lively debate over UBI took place among economists who foresaw the situation Watts describes and also sought to simplify the Byzantine means-tested welfare system. The usual congressional bickering eventually killed Universal Basic Income in 1972, but most Americans would be surprised to discover how close the country actually came to implementing it, under a Republican president. (There are now existing versions of UBI, or revenue sharing schemes in limited form, in Alaska, and several countries around the world, including the largest experiment in history happening in Kenya.)

To learn more about the long history of basic income ideas, see this chronology at the Basic Income Earth Network. Watts mentions his own source for many of his ideas on the subject, Robert Theobald, whose 1963 Free Men and Free Markets defied left and right orthodoxies, and was consistently mistaken for one or the other. (Theobald introduced the term guaranteed basic income.) Watts, who would be 101 today, had other thoughts on economics in his essay “Wealth Versus Money.” Some of these now seem, writes Maria Popova at Brain Pickings, “bittersweetly naïve” in retrospect. But when it came to technological “disruptions” of capitalism and the effect on work, Watts was cannily perceptive. Perhaps his ideas about basic income were as well.

Related Content:

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

Alan Watts On Why Our Minds And Technology Can’t Grasp Reality

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness