Most of my generation’s exposure to Japanese culture came heavily mediated by anime and samurai films. One cultural artifact that stands out for me is TV miniseries Shogun, an adaptation of James Clavell’s popular novel, which gives us a view of Japan through the eyes of a British novelist and his British hero (played by Richard Chamberlain in the film). Shogun depicts a feudal Japanese warrior culture centered on exaggerated displays of masculinity, with women operating in the margins or behind the scenes.

Even the great Akira Kurosawa’s visions of feudal Japan, like The Seven Samurai, are “not exactly inundated with the stunning power of female warriors brandishing katanas,” writes Dangerous Minds, “it’s a bit of a ソーセージ-fest.”

And yet, it turns out, “such women did exist.” Known as onna bugeisha, these fighters “find their earliest precursor in Empress Jingū, who in 200 A.D. led an invasion of Korea after her husband Emperor Chūai, the fourteenth emperor of Japan, perished in battle.” Empress Jingū’s example endured. In 1881, she became the first woman on Japanese currency.

Preceding the all-male samurai class depicted in Clavell and Kurosawa, the onna bugeisha “learned to use naginata, kaiken, and the art of tanto Jutso in battle,” the Vintage News tells us. Rather than pay mercenaries to defend them, as the terrified townsfolk do in Seven Samurai, these women trained in battle to protect “communities that lacked male fighters.”

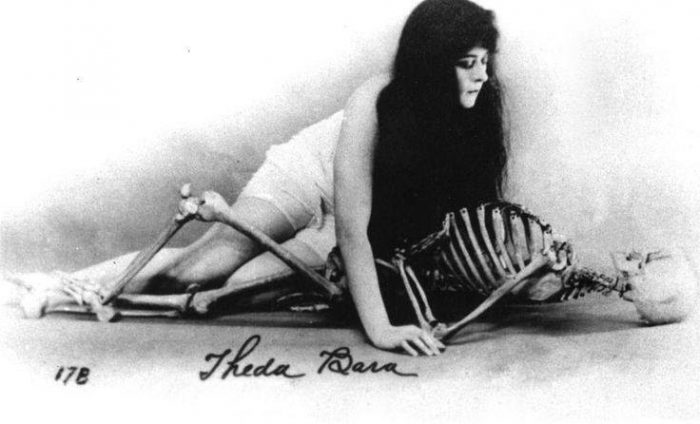

The onna bugeisha’s ethic was as purportedly as uncompromising as the samurai, and it shows in these fierce portraits from the 1800s. Although many tales of prominent onna bugeisha come from the 12th-13th centuries, one famous figure, Nakano Takeko lived in the 19th century, writes Dangerous Minds, and died quite the warrior’s death:

While she was leading a charge against Imperial Japanese Army troops she was shot in the chest. Knowing her remaining time on earth to be short, Takeko asked her sister, Yūko, to cut her head off and have it buried rather than permit the enemy to seize it as a trophy. It was taken to Hōkai Temple and buried underneath a pine tree.

Another revered fighter, Tomoe Gozen, appears in The Tale of the Heike (often called the “Japanese Iliad). She is described as “especially beautiful,” and also as “a remarkably strong archer… as a swordswoman she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot.”

In the photos here—and many more at The Vintage News—we get a sense of what such a legendary badass may have looked like.

via Vintage News/Dangerous Minds

Related Content:

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

How Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai Perfected the Cinematic Action Scene: A New Video Essay

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness