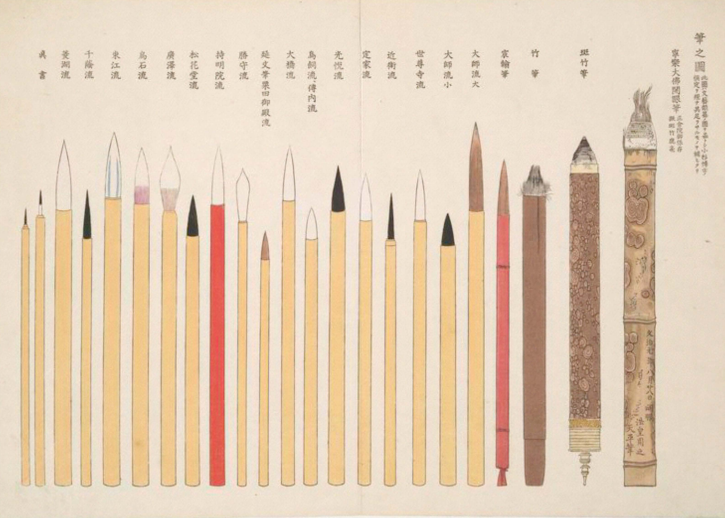

Calling all coloring book lovers. You can now take part in #ColorOurCollections 2017–a campaign where museums and libraries worldwide will make available free coloring books, letting you color artwork from their collections and then share it on Twitter and other social media platforms. When sharing, use the hashtag #ColorOurCollections.

Below you can find a collection of free coloring books, which you can download and continue to enjoy. If you see any that we’re missing, please let us know in the comments, and we’ll do our best to update the page. To see the free coloring books that were offered up in 2016, click here.

Color Our Collections is organized by The New York Academy of Medicine Library. So please give them thanks.

- New York Academy of Medicine

- The New York Botanical Garden Coloring Book

- The New York Public Library Coloring Book

- Smithsonian Libraries Coloring Book

- Cambridge University Library Coloring Book

- Chemical Heritage Foundation Coloring Book

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Coloring Book

- Newberry Library Coloring Book

- American Bookbinders Museum Coloring Book

- Auraria Library Coloring Book

- Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Santé, Paris Coloring Book

- Biodiversity Heritage Library Coloring Book Part 1

- Biodiversity Heritage Library Coloring Book Part 2

- Biodiversity Heritage Library Coloring Book Part 3

- Biodiversity Heritage Library Coloring Book Part 4

- Biodiversity Heritage Library Coloring Book Part 5

- Bodleian Library at Oxford University

- Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection Coloring Sheets

- Dittrick Medical History Center Coloring Book

- Digital Library@Villanova University Coloring Books

- Digita Vaticana Coloring Book

- Europeana Art Nouveau Color Book

- Europeana Colouring Book

- Frances Willard Memorial Library and Archives Coloring Sheet

- Health Sciences Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Coloring Book

- Hunter College Libraries – City University of New York Coloring Book

- The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

- James Madison University Libraries Coloring Book

- Marian Library, University of Dayton

- National Library of Medicine Coloring Book

- National Museum Wales Coloring Book

- New York Academy of Medicine Famous Women Coloring Sheet

- OHSU Historical Collections & Archives Coloring Sheets

- Royal College of Physicians

- Special Collections and Archives, Trexler Library, Muhlenberg College Coloring Books

- The Rosenbach Coloring Sheets

- University of Calgary Libraries and Cultural Resources

- University of Houston Special Collections Coloring Book

- University of Oregon Coloring Book

- University of Scranton Archives and McHugh Special Collections Coloring Book

- University of Puget Sound, Collins Memorial Library, Archives & Special Collections Coloring Book

- University of Reading Museums and Collections Coloring Book

- Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine, University of Minnesota Libraries

- Williams College Libraries Coloring Sheets

Looking for free, professionally-read audio books from Audible.com? Here’s a great, no-strings-attached deal. If you start a 30 day free trial with Audible.com, you can download two free audio books of your choice. Get more details on the offer here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The First Adult Coloring Book: See the Subversive Executive Coloring Book From 1961

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!