More and more, museums around the world are opening up their vast archives for free on the internet. We can browse broad collections, or dig down deep into collections and examine individual works, or we can download hi-resolution jpgs of famous works and slap them on our new desktop as wallpaper. (Discussion: does this trivialize a work or help us appreciate it?)

Indeed, OpenCulture has linked to many of these and I’ve followed. And I’ve often returned overwhelmed or disappointed, not by the art, but by bad web design. Good intentions are one thing, but institutions often turn to coders first, not designers. And there’s a difference.

Recently we told you how the Metropolitan Museum of Art has put most of its nearly 90 years of exhibitions online. Our own Colin Marshall said:

The archive offers, in the words of Chief of Archives Michelle Elligott, “free and unprecedented access to The Museum of Modern Art’s ever-evolving exhibition history” in the form of “thousands of unique and vital materials including installation photographs, out-of-print exhibition catalogues, and more, beginning with MoMA’s very first exhibition in 1929.”

Yet the interface is quite lacking, showing a blank search bar with no clue to how much lies beneath. Where to start, if you just want to browse?

Enter the data visualization firm of Good, Form & Spectacle, who excel at presenting archives in different ways. Commissioned by MoMA to make something from the data, the firm’s “MoMA Exhibition Spelunker” offers 60 years of exhibition data that can then be searched by “curators, arrangers, designers, artists, and others” with connections available at every level.

For example, the second ever MoMA exhibit, “Painters by 19 Living Americans” (1929 — 1930), featured Edward Hopper. The official archive will show you the exhibition catalog and press release. But go spelunking and we discover that up until 1989 (the end of the archive for now), Hopper was featured in 61 exhibitions, including 1943 where he was featured in four exhibits in one year. What were those exhibits? Well, down the rabbit hole you go.

Coder (and, full disclosure, friend since high school) Phil Gyford spoke about his work on the page:

A spelunker, according to Chambers, is “a person who explores caves as a hobby” and we aimed to explore MoMA’s raw data and make it more visible and penetrable by everyone else. It’s hard to get a decent sense of the shape of lists of data so we set off to explore.

Good, Form & Spectacle have worked on other sleek and minimal sites, including a Netflix recommendation engine, a smaller spelunker for the Victoria & Albert Museum, and a larger one for the British Museum.

But if you’re interested in exploring a century of exhibitions at MoMA, then spend as much time as you like with the “MoMA Exhibition Spelunker.”

Related Content:

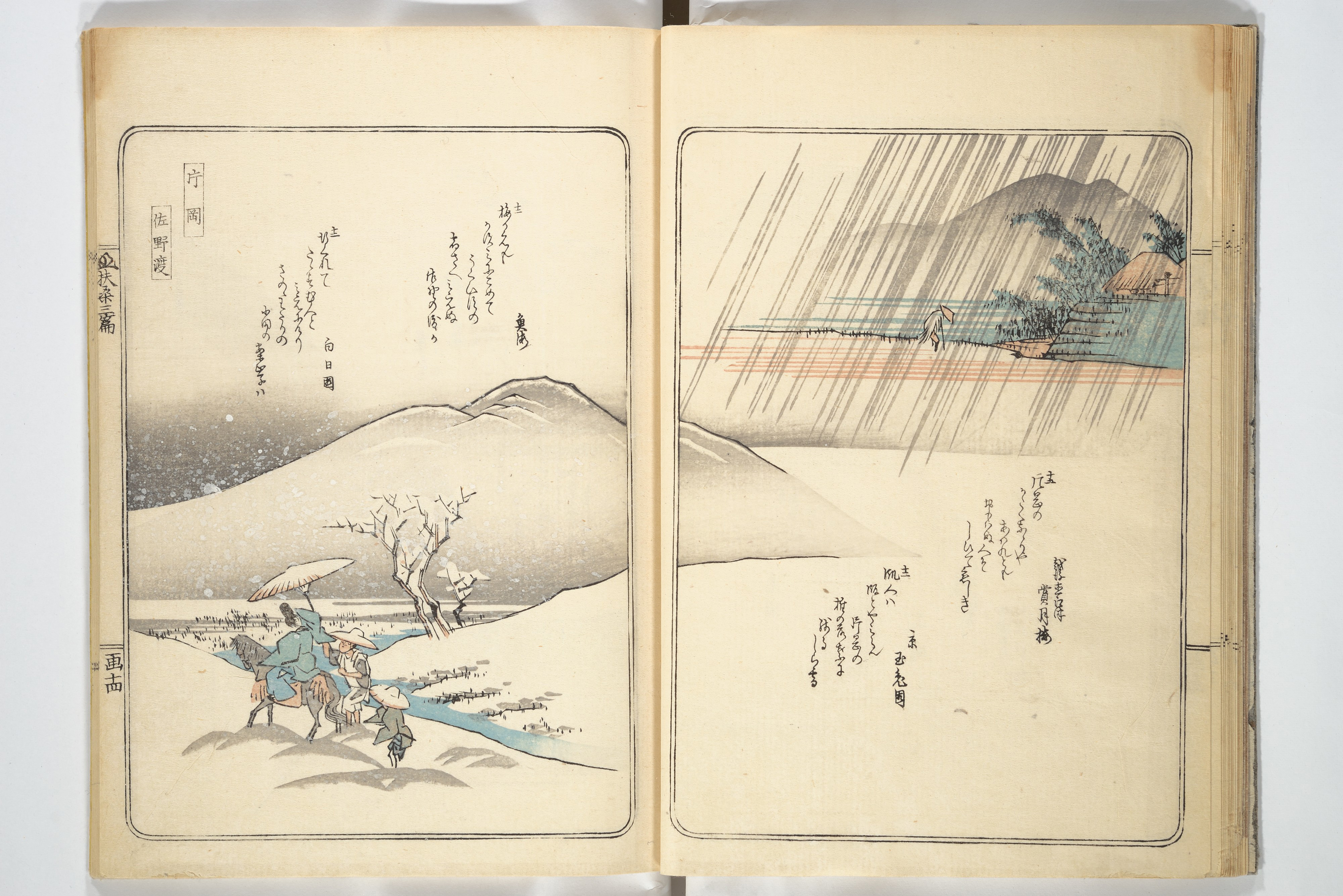

1.8 Million Free Works of Art from World-Class Museums: A Meta List of Great Art Available Online

Download 464 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Google Art Project Expands, Bringing 30,000 Works of Art from 151 Museums to the Web

Download 397 Free Art Catalogs from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Puts Online 65,000 Works of Modern Art

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.