We cannot rightly see ourselves without honest feedback. Those who surround themselves with sycophants and people just like them only hear what they want to hear, and never get an accurate sense of their capabilities and shortcomings. And so the best feedback often comes from people outside our in-groups. This can be as true of nations as it can be of individuals, provided our critics are charitable, even when unsparingly honest, and that they take a genuine interest in our well-being.

These qualities well describe one of the sharpest critics of the United States in the past two centuries. Alexis de Tocqueville, aristocratic French lawyer, historian, and political philosopher, who traveled to the fledgling country in 1831 to observe a nation then in the grip of a populist fever under Andrew Jackson, a president who became notorious for his expropriation of indigenous land, ruthless relocation policies, and embrace of Southern slavery. But the groups who flourished under Jackson’s rule did so with a tremendous enthusiasm that the French thinker admired but also viewed with a very skeptical eye.

De Tocqueville published his observations and analyses of the United States in a now-famous book, Democracy in America. Though we’ve come to take the idea of democracy for granted, for the young Frenchman, a child of Napoleonic Europe, it was “a highly exotic and new political option,” as Alain de Botton tells us in his animated video introduction above. De Tocqueville “presciently believed that democracy was going to be the future all over the world, and so he wanted to know, ‘what would that be like?’”

With a grant from the French government, De Tocqueville traveled the country (then less than half its current size) for nine months, getting to know its people and customs as best he could, and making a series of general observations that would form the vignettes and arguments in his book. He was “particularly alive to the problematic and darker sides of democracy.” De Botton discusses five critical insights from Democracy in America. See three of them below, with quotes from De Tocqueville himself.

1. Democracy Breeds Materialism.

For De Tocqueville one kind of materialism—the excessive pursuit of wealth—disposed the country to another, “a dangerous sickness of the human mind”—the denial of a spiritual or intellectual life. “While man takes pleasure in this honest and legitimate pursuit of well-being,” he wrote, “it is to be feared that in the end he may lose the use of his most sublime faculties, and that by wanting to improve everything around him, he may in the end degrade himself.”

De Tocqueville, says De Botton, observed that “money seemed to be quite simply the only achievement that Americans respected” and that “the only test of goodness for any item was how much money it happens to make.”

2. Democracy Breeds Envy & Shame

“When all the prerogatives of birth and fortune have been abolished,” wrote De Tocqueville, “when every profession is open to everyone, an ambitious man may think it is easy to launch himself on a great career and feel that he has been called to no common destiny. But this is a delusion which experience quickly corrects.” Unable to rise above his circumstances, and yet believing that he should be equal to his neighbors in achievements, such a person may blame himself and feel ashamed, or succumb to envy and ill will.

De Tocqueville was far too optimistic about the abolishment of “prerogatives of birth and fortune,” but many Americans might recognize themselves still in his general picture, in which “the sense of unlimited opportunity could initially encourage a surface cheerfulness.” And yet, De Botton notes, “as time passed and the majority failed to raise themselves, Tocqueville noted that their mood darkened, that bitterness took hold and choked their spirits, and that their hatred of themselves and their masters grew fierce.”

3. Tyranny of the Majority

De Tocqueville, De Botton says, thought that “democratic culture… often ends up demonizing any assertion of difference, and especially cultural superiority, even though such attitudes might be connected with real merit.” In such a state, “society has an aggressive leveling instinct.”

It wasn’t only attacks on high culture that De Tocqueville feared, but what he called the “Omnipotence of the Majority,” a phrase he used to denote the power of public opinion as an almost totalitarian means of social control. In volume two of his study, published in 1840, De Tocqueville devoted particular attention to “the power which that majority naturally exercises over the mind…. By whatever political laws men are governed in the ages of equality, it may be foreseen that faith in public opinion will become for them a species of religion, and the majority its ministering prophet.”

From this prediction, De Tocqueville foresaw “two tendencies; one leading the mind of every man to untried thoughts, the other prohibiting him from thinking at all.”

De Botton goes on to discuss two closely related critiques: democracy’s suspicion of all authority and its undermining of free thought. Rather than encountering the kind of marketplace of ideas the country prides itself on fostering, he found in few places “less independence of mind, and true freedom of discussion, than in America.” The criticism is harsh, and De Tocqueville did not flatter his hosts often, and yet for all of its “inherent drawbacks,” De Botton writes at the School of Life, the Frenchman “isn’t anti-democratic.”

His aim is “to get us to be realistic” about democratic society and its tendencies to inhibit rather than enlarge many freedoms. As Arthur Goldhammer observes at The Nation, De Tocqueville believed that “True freedom lay not in the pursuit of individualistic aims, but “in ‘slow and tranquil’ action in concert with others sharing some collective purpose.”

Related Content:

Why Socrates Hated Democracies: An Animated Case for Why Self-Government Requires Wisdom & Education

20 Lessons from the 20th Century About How to Defend Democracy from Authoritarianism, According to Yale Historian Timothy Snyder

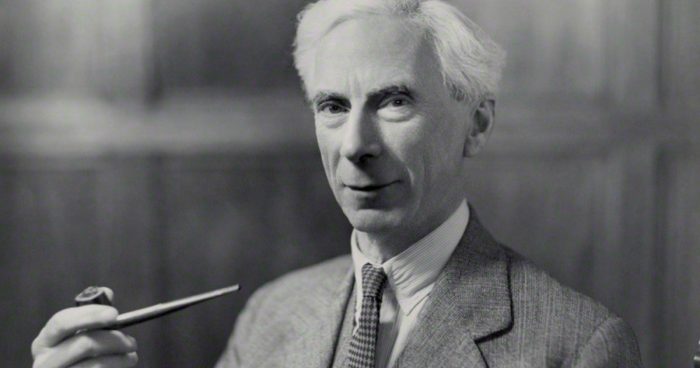

Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness