As a number of commentators have noted, it has already happened here in the past—that is, the fervid nativism, immigration bans, and mass deportations, the nationalist, fanatically religious, anti-democratic militancy… many of the characteristics of American authoritarianism, in other words. In the political climate we face today, these strains have come together in some very overt ways, under the leadership of a purportedly charismatic leader who swayed millions of followers with the promise of renewed “greatness.”

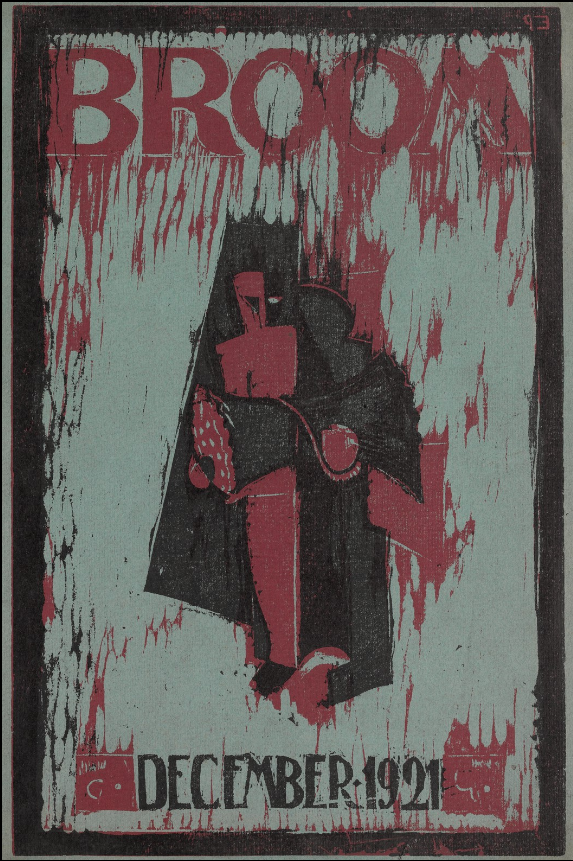

The questions that now arise are those once asked by It Can’t Happen Here, the 1935 novel by Sinclair Lewis that imagined the election of a charismatic leader who promises greatness, “then quickly becomes a dictator,” writes the American Library Association’s Public Programs Office, “enacting martial law and throwing dissenters into labor camps.” The novel resonated with a public increasingly concerned about rising dictatorships in Europe, as well as the growing power of the presidency at home. “Shortly after it was published,” the ALA notes, “the novel was recreated as a play and opened in 21 cities nationwide on October 27, 1936.”

You can see some still images of an original It Can’t Happen Here production in the video above about the Federal Theater Project. Last year—almost eighty years after the play’s debut and just days before the presidential election—several dozen theaters, universities, and libraries across the country held readings of Lewis’ theatrical adaptation. See one such reading at the top of the post, performed on October 24 at the Yolo County Library in Northern California by the Berkeley Repertory Theatre, who at the time also staged a full, two part production of It Can’t Happen Here that was both “thrilling and grim,” as Alexander Nazaryan writes at The New Yorker. (See a trailer below)

The Berkeley Rep’s production significantly rewrote Lewis’ adaptation, which they decided was “terrible.” But the novel itself is not quite a literary masterpiece. “Lewis was never much of an artist,” Nanaryan notes, “but what he lacked in style he made up for with social observation.” While his skills as a close observer of American political tendencies may still be unmatched, the prescience of his novel in imagining the situation we find ourselves in today may have as much to do with Lewis’ abilities as with the recurrence of certain depressing themes in American political life. As Alex Wagner writes at The Atlantic, the mass deportations and raids on immigrant populations that have now increased in cities nationwide saw a chilling precedent in the 1920s and 30s, “a time of economic struggle, racial resentment and increasing xenophobia.”

Then, Herbert Hoover, “promised jobs for Americans—and made good on that promise by slashing immigration by nearly 90 percent” and deporting as many as “1.8 million men, women and children” of Mexican descent or with “a Mexican-sounding name.” As many as sixty percent of those deported were U.S. citizens. We’ve seen in recent months numerous comparisons of our current political situation to Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. While these may be warranted in many respects, they may also be superfluous. To understand the origins of racist authoritarianism in America, we need only look back to several moments in our own history, those that Lewis closely observed and satirized in a novel that once again shows us an image of the country that many people have chosen not to see.

This reading will be added to our list, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

How to Recognize a Dystopia: Watch an Animated Introduction to Dystopian Fiction

George Orwell’s Final Warning: Don’t Let This Nightmare Situation Happen. It Depends on You!

Philosopher Richard Rorty Chillingly Predicts the Results of the 2016 Election … Back in 1998

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for FreeJosh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness