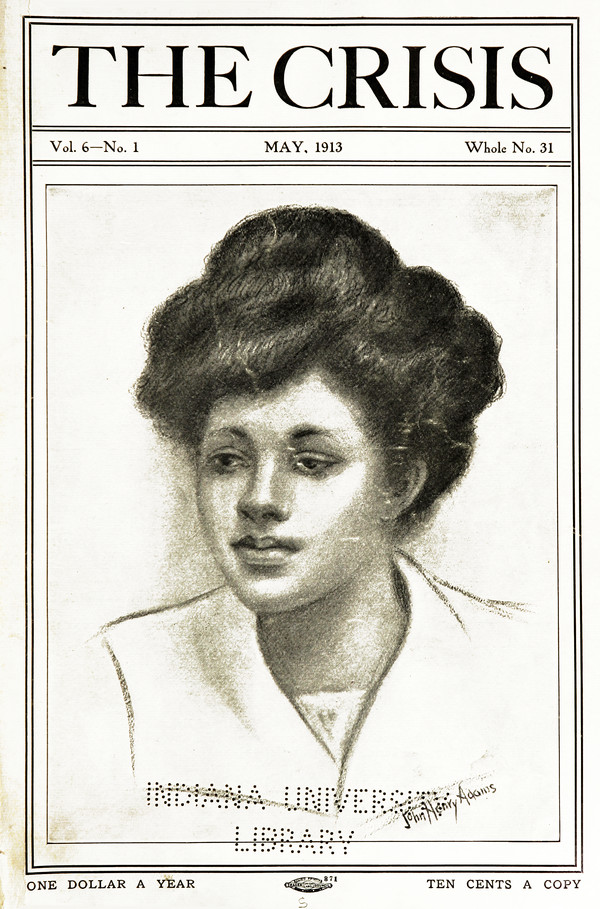

We recognize its hallmarks in music especially. It is the province of Sun Ra, George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic, Afrika Bambaataa, and, in recent years, Janelle Monae, Andre 3000, Beyoncé, and many other black artists who have updated for the 21st century the styles and sounds of Afrofuturism. Reaching back into an Afrocentric past—with heavy emphasis on Egyptology—and forward to an interstellar future, the genre of Afrofuturism reclaims the terrain of science fiction for people of African descent, serving as an “umbrella term,” as one contemporary Afrofuturist community puts it, “for the Black presence in sci-fi, technology, magic, and fantasy.”

One might be surprised to learn that the term itself did not originate with the visionary founder of its aesthetic. Sun Ra (formerly Herman Poole Blount)—bandleader of the Arkestra and space alien from Saturn—called his space-themed big band music “cosmic jazz” or, sometimes, “phre music—music of the sun.” Instead, “Afrofuturism” was coined by cultural critic Mark Dery in his seminal 1994 essay “Black to the Future,” which included interviews with sci-fi author Samuel R. Delany, critic and musician Greg Tate, and scholar Tricia Rose. Afrofuturism has taken on a variety of meanings, not only in music, but also in art, dance, film, and science fiction writing like that of Delany and Octavia Butler.

But as you’ll learn in the video above, the first in a 5‑part animated series on the genre from Dust, “its roots go back to the late 1930s in Huntsville, Alabama,” the actual birthplace of Sun Ra, where he maintained he was abducted, taken to Saturn (not Jupiter, as the narrator mistakenly says), and told by aliens to “transport black people away from the violence and racism of planet Earth.” The series traces the growth of Sun Ra’s original mission through the cultural touchstones of Lieutenant Uhura, George Clinton, Jimi Hendrix, and Missy Elliott.

Sun Ra died in 1993, the year before Dery invented the name for his generous legacy. “What does it say,” the narrator asks, “about how far we have or have not come if this message still resonates with each new generation?” Dery recently took on the question in a 2016 essay, in which he quotes Tate—now at work on a book on Afrofuturism: “Having ceded the racial ground war to Enlightenment-era imperialism somewhere back in the 17th century, black futurism determined that the fiery realms of the symbolic and the mythic and the rhetorical and the spiritual and the wickedly stylish, sonic, and polyrhythmic would become our culture’s bailiwick, raison d’être, and cultural triumphalist battleground.”

Afrofuturism transforms trauma, the erasure of the black past, and bleak prospects for the future into powerful displays of creative agency. The struggle to claim that agency in the face of imperial violence and plunder continues, Dery argues, but now takes place in the midst of technological developments even a space alien like Sun Ra could not have foreseen. While many of the questions once asked about the humanity of enslaved people have shifted to debates over androids, cyborgs, and other posthuman creations, the conditions for many colonized and marginalized people all over the world have not considerably improved.

As “Afrofuturism is all too aware,” Dery writes, “objects can have inner lives…. Consequently, it is less concerned with knocking the human off its ontological perch than it is in forging alliances with Others of any species, human or posthuman.”

Afrofuturism speaks to our moment because it alone – not the ahistorical, apolitical corporate precogs at TED talks; not the fatuous Hollywood franchises that have nothing to say about our times – offers a mythology of the future present, an explanatory narrative that recovers the lost data of historical memory, confronts the dystopian reality of black life in America, demands a place for people of color among the monorails and the Hugh Ferris monoliths of our tomorrows, insists that our Visions of Things to Come live up to our pieties about racial equality and social justice.

You can see three short episodes of Dust’s Afrofuturism series above, with parts four and five to come. (You will be able to find them all here.) Until then, watch the short Vox video explainer on Afrofuturism below.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness