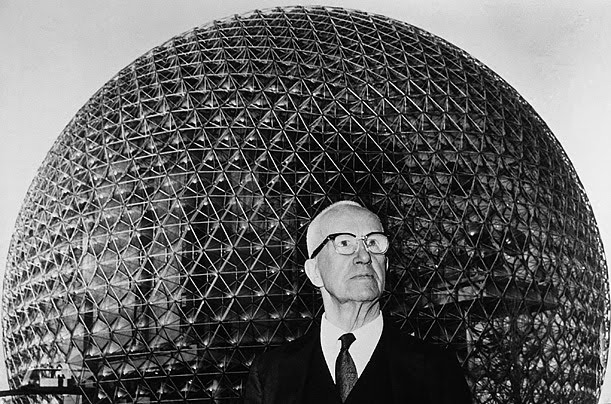

One potential drawback of genius, it seems, is restlessness, a mind perpetually on the move. Of course, this is what makes many celebrated thinkers and artists so productive. That and the extra hours some gain by sacrificing sleep. Voltaire reportedly drank up to 50 cups of coffee a day, and seems to have suffered no particularly ill effects. Balzac did the same, and died at 51. The caffeine may have had something to do with it. Both Socrates and Samuel Johnson believed that sleep is wasted time, and “so for years has thought grey-haired Richard Buckminster Fuller,” wrote Time magazine in 1943, “futurific inventor of the Dymaxion house, the Dymaxion car and the Dymaxion globe.”

Engineer and visionary Fuller intended his “Dymaxion” brand to revolutionize every aspect of human life, or—in the now-slightly-dated parlance of our obsession with all things hacking—he engineered a series of radical “lifehacks.” Given his views on sleep, that seemingly essential activity also received a Dymaxion upgrade, the trademarked name combining “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension.” “Two hours of sleep a day,” Fuller announced, “is plenty.” Did he consult with specialists? Medical doctors? Biologists? Nothing as dull as that. He did what many a mad scientist does in the movies. (In the search, as Vincent Price says at the end of The Fly, “for the truth.”) He cooked up a theory, and tested it on himself.

“Fuller,” Time reported, “reasoned that man has a primary store of energy, quickly replenished, and a secondary reserve (second wind) that takes longer to restore.” He hypothesized that we would need less sleep if we stopped to take a nap at “the first sign of fatigue.” Fuller trained himself to do just that, forgoing the typical eight hours, more or less, most of us get per night. He found—as have many artists and researchers over the years—that “after a half-hour nap he was completely refreshed.” Naps every six hours allowed him to shrink his total sleep per 24-hour period to two hours. Did he, like the 50s mad scientist, become a tragic victim of his own experiment?

No danger of merging him with a fly or turning him invisible. The experiment’s failure may have meant a day in bed catching up on lost sleep. Instead, Fuller kept up it for two full years, 1932 and 1933, and reported feeling in “the most vigorous and alert condition that I have ever enjoyed.” He might have slept two hours a day in 30 minute increments indefinitely, Time suggests, but found that his “business associates… insisted on sleeping like other men,” and wouldn’t adapt to his eccentric schedule, though some not for lack of trying. In his book BuckyWorks J. Baldwin claims, “I can personally attest that many of his younger colleagues and students could not keep up with him. He never seemed to tire.”

A research organization looked into the sleep system and “noted that not everyone was able to train themselves to sleep on command.” The point may seem obvious to the significant number of people who suffer from insomnia. “Bucky disconcerted observers,” Baldwin writes, “by going to sleep in thirty seconds, as if he had thrown an Off switch in his head. It happened so quickly that it looked like he had had a seizure.” Buckminster Fuller was undoubtedly an unusual human, but human all the same. Time reported that “most sleep investigators agree that the first hours of sleep are the soundest.” A Colgate University researcher at the time discovered that “people awakened after four hours’ sleep were just as alert, well-coordinated physically and resistant to fatigue” as those who slept the full eight.

Sleep research since the forties has made a number of other findings about variable sleep schedules among humans, studying shift workers’ sleep and the so-called “biphasic” pattern common in cultures with very late bedtimes and siestas in the middle of the day. The success of this sleep rhythm “contradicts the normal idea of a monophasic sleeping schedule,” writes Evan Murray at MIT’s Culture Shock, “in which all our time asleep is lumped into one block.” Biphasic sleep results in six or seven hours of sleep rather than the seven to nine of monophasic sleepers. Polyphasic sleeping, however, the kind pioneered by Fuller, seems to genuinely result in even less needed sleep for many. It’s an idea that’s only become widespread “within roughly the last decade,” Murray noted in 2009. He points to the rediscovery, without any clear indebtedness, of Fuller’s Dymaxion system by college student Maria Staver, who named her method “Uberman,” in honor of Nietzsche, and spread its popularity through a blog and a book.

Murray also reports on another blogger, Steve Pavlina, who conducted the experiment on himself and found that “over a period of 5 1/2 months, he was successful in adapting completely,” reaping the benefits of increased productivity. But like Fuller, Pavlina gave it up, not for “health reasons,” but because, he wrote, “the rest of the world is monophasic” or close to it. Our long block of sleep apparently contains a good deal of “wasted transition time” before we arrive at the necessary REM state. Polyphasic sleep trains our brains to get to REM more quickly and efficiently. For this reason, writes Murray, “I believe it can work for everyone.” Perhaps it can, provided they are willing to bear the social cost of being out of sync with the rest of the world. But people likely to practice Dymaxion Sleep for several months or years probably already are.

Related Content:

The Power of Power Naps: Salvador Dali Teaches You How Micro-Naps Can Give You Creative Inspiration

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

Everything I Know: 42 Hours of Buckminster Fuller’s Visionary Lectures Free Online (1975)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness