The use of an author’s name as an adjective to describe some kind of general style can seem, well, lazy, in a wink-wink, “you know what I mean,” kind of way. One must leave it to readers to decide whether deploying a “Baldwinian” or a “Woolfian,” or an “Orwellian” or “Dickensian,” is justified. When it comes to “Kafkaesque,” we may find reason to consider abandoning the word altogether. Not because we don’t know what it means, but because we think it means what Kafka meant, rather than what he wrote. Maybe turning him into shorthand, “a clever reference,” writes Chris Barsanti, prepares us to seriously misunderstand his work.

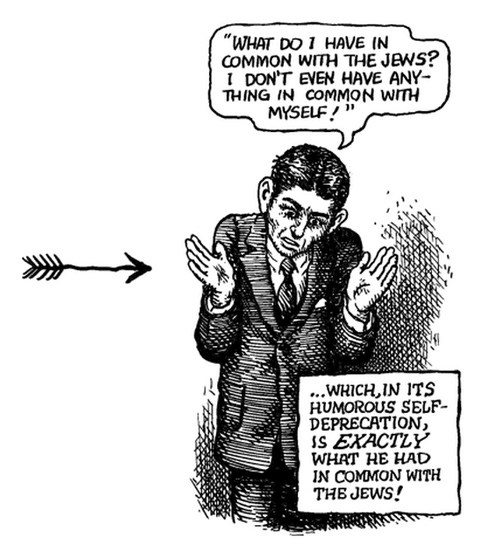

The problem motivated author David Zane Mairowitz and underground comics legend Robert Crumb to create a graphic biography, first published in 1990 as Kafka for Beginners. “The book,” writes Barsanti of a 2007 Fantographics edition called Kafka, “states its case rather plain: ‘No writer of our time, and probably none since Shakespeare, has been so widely over-interpreted and pigeon holed… [Kafkaesque] is an adjective that takes on almost mythic proportions in our time, irrevocably tied to fantasies of doom and gloom, ignoring the intricate Jewish Joke that weaves itself through the bulk of Kafka’s work.’” Or, as Maria Popova puts it, “Kafka’s stories, however grim, are nearly always also… funny.”

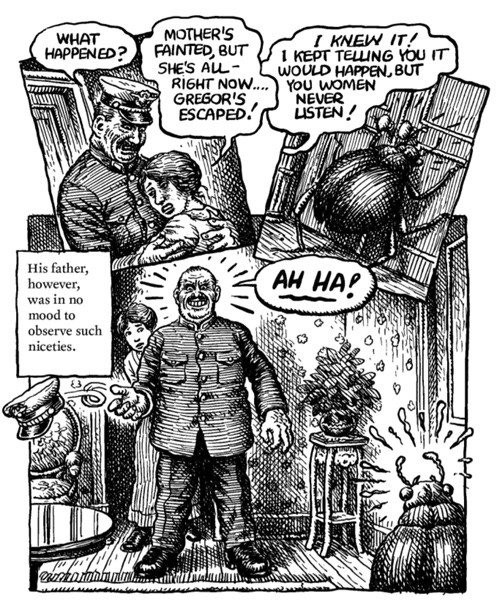

Much of that humor derives from “the author’s coping mechanisms amid Prague’s anti-Semitic cultural climate.” Mairowitz describes Kafka’s Jewish humor as “healthy anti-Semitism.… but sooner or later, even the most hateful of Jewish self-hatreds has to turn around and laugh at itself.” Crumb provides graphic illustrations of Kafka’s especially mordant, absurdist humor in adaptations of The Metamorphosis, A Hunger Artist, In the Penal Colony, and The Judgement and brief sketches from The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika. These illustrations draw out the grotesque nature of Kafka’s humor from the start, Barstanti notes, “with a gruesome graphic rendering of Kafka’s nightmares of his own death.”

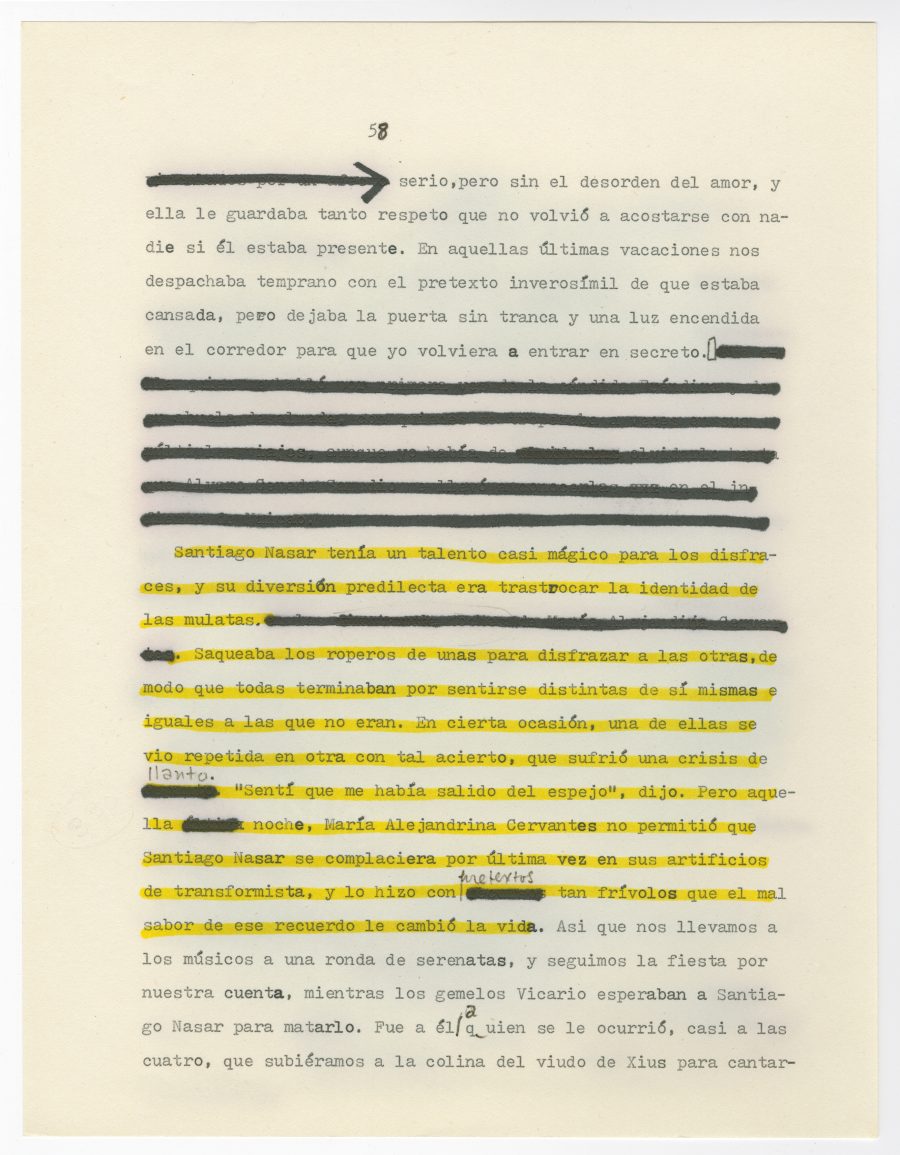

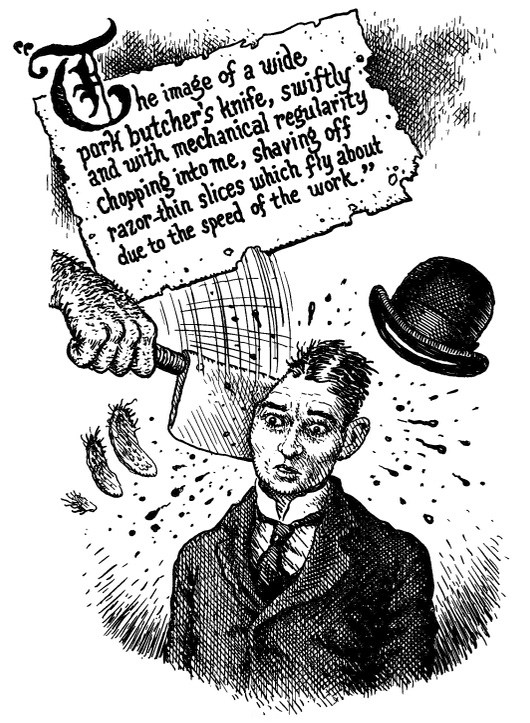

Kafka’s self-violence leaps out at us in its incredible specificity, which can produce horrors, like the ghoulish execution of “In the Penal Colony,” and darkly funny fantasies like a “pork butcher’s knife” sending thin slices of Kafka flying around the room, “due to the speed of the work.” Turned into cold cuts, as it were. Crumb’s illustration (top), imagines this grisly joke with exquisite glee—halo of blood spurts like squiggly exclamation marks and bowler hat taking flight. Along with Mairowitz’s literary analysis and biographical detail, Crumb’s finely rendered illustrations make Kafka an “invaluable book,” Barsanti writes, one that gives Kafka “back his soul.”

One only wishes they had paid more attention to Kafka’s weird animal stories, some of the funniest he ever wrote. Stories like “Investigations of a Dog” and “In Our Synagogue” express with more vivid imagination and wicked humor Kafka’s profoundly ambivalent relationship to Judaism and to himself as a “tortured, gentle, cruel, and brilliant,” and yet very funny, outsider.

Related Content:

What Does “Kafkaesque” Really Mean? A Short Animated Video Explains

Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness