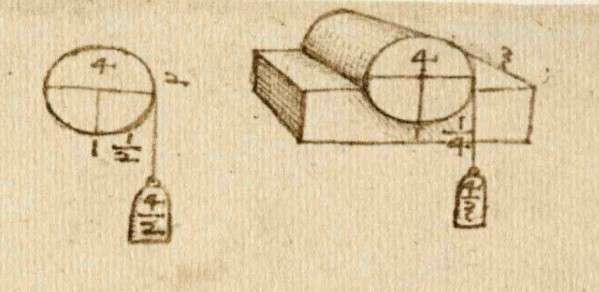

Just like the rest of us, Leonardo da Vinci doodled and scribbled: you can see it in his digitized notebooks, which we featured this past summer. But the prototypical Renaissance man, both unsurprisingly and characteristically, took that scribbling and doodling to a higher level entirely. Not only do his margin notes and sketches look far more elegant than most of ours, some of them turn out to reveal his previously unknown early insight into important subjects. Take, for instance, the study of friction (otherwise known as tribology), which may well have got its start in what at first just looked like doodles of blocks, weights, and pulleys in Leonardo’s notebooks.

This discovery comes from University of Cambridge engineering professor Ian M. Hutchings, whose research, says that department’s site, “examines the development of Leonardo’s understanding of the laws of friction and their application. His work on friction originated in studies of the rotational resistance of axles and the mechanics of screw threads, but he also saw how friction was involved in many other applications.”

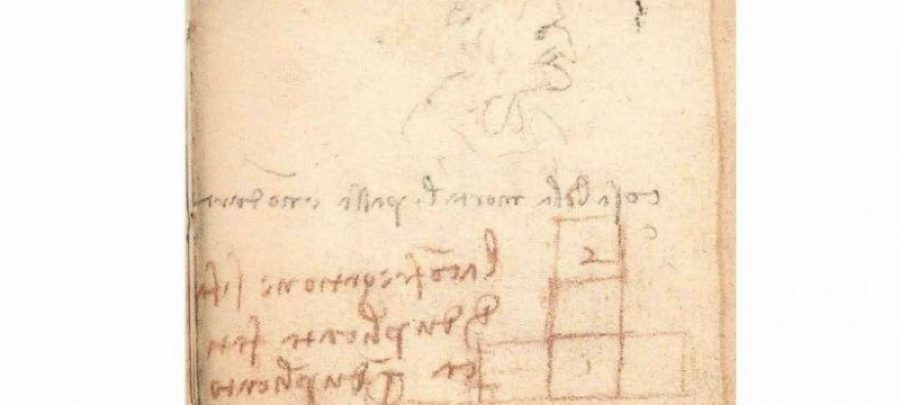

One page, “from a tiny notebook (92 x 63 mm) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, dates from 1493” and “contains Leonardo’s first statement of the laws of friction,” sketches of “rows of blocks being pulled by a weight hanging over a pulley – in exactly the same kind of experiment we might do today to demonstrate the laws of friction.”

“While it may not be possible to identify unequivocally the empirical methods by which Leonardo arrived at his understanding of friction,” Hutchings writes in his paper, “his achievements more than 500 years ago were outstanding. He made tests, he observed, and he made powerful connections in his thinking on this subject as in so many others.” By the year of these sketches Leonardo “had elucidated the fundamental laws of friction,” then “developed and applied them with varying degrees of success to practical mechanical systems.”

And though tribologists had no idea of Leonardo’s work on friction until the twentieth century, seemingly unimportant drawings like these show that he “stands in a unique position as a quite remarkable and inspirational pioneer of tribology.” What other fields of inquiry could Leonardo have pioneered without history having properly acknowledged it? Just as his life inspires us to learn and invent, so research like Hutchings’ inspires us to look closer at what he left behind, especially at that which our eyes may have passed over before. You can open up Leonardo’s notebooks and have a look yourself. Just make sure to learn his mirror writing first.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.