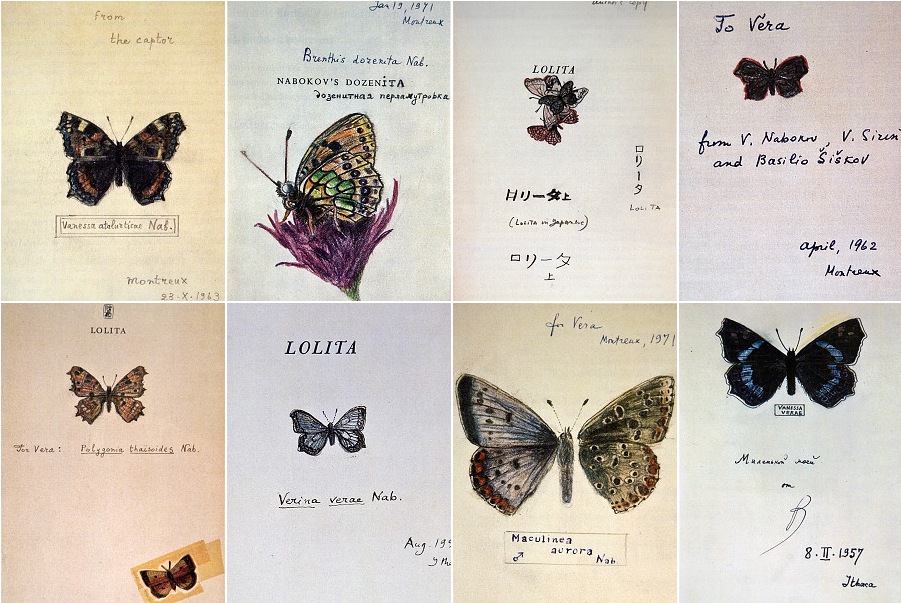

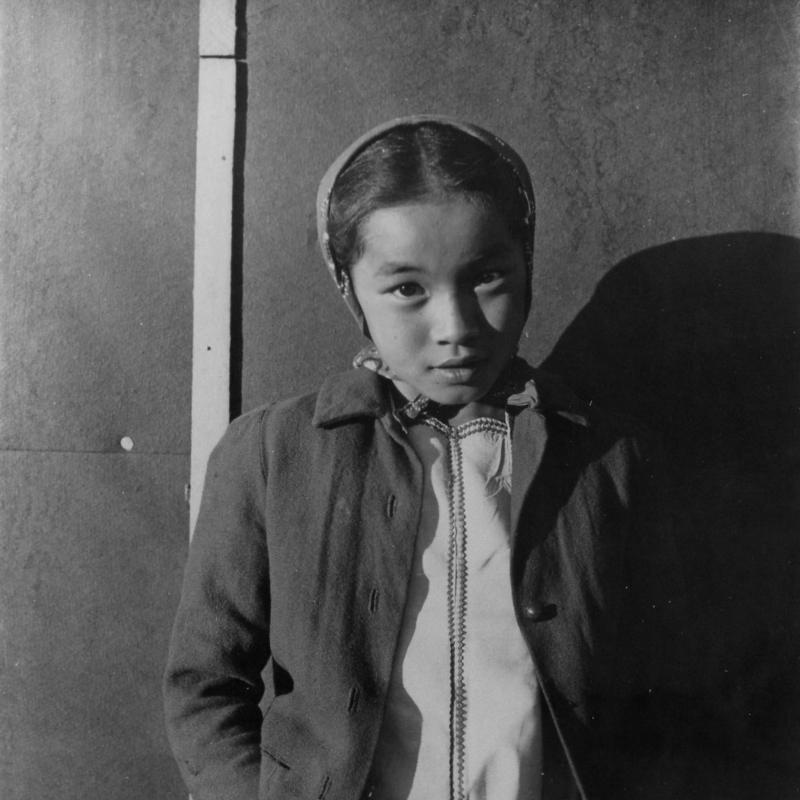

Image of Woody Guthrie by Al Aumuller, via Wikimedia Commons

Marshall McLuhan’s chestnut “the medium is the message” contains some of the most important theory about mass media to have emerged in the past century. In its honor, we might propose another slogan—less conceptually tidy and alliterative—that brings to mind the arguments of critical theorists like Theodor Adorno: “the economy is the culture”—the economic mechanisms that govern the “culture industry,” as Adorno would say, determine the kinds of productions that saturate our shared environment. In a purely corporate capitalist model, we consume culture—that which is marketed most aggressively and distributed most plentifully—and often discard it just as quickly. In an economy that doesn’t make profit the fulcrum of its every move, things go otherwise. The lines between consumers, creators, and communities become blurred in weird and wonderful ways.

This can happen in decentralized environments like the wilds of the early internet. And it can happen in institutions that code it into their design. The Smithsonian is one of those institutions. The public collections in its vast network of museums has remained, outside of special exhibits and films, free and “open access” for everyone. And one of their key cultural contributions, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, has devoted itself since its founding in the late sixties to “culture of, by, and for the people.”

Even if you’ve never taken the time to delve into their curatorial efforts (and you should), you’ll know their work through Folkways Recordings, the record label created in by Moses Asch—founder of Folkways Records in 1949. After he passed away in 1986, Asch’s family donated over 2,000 records, his entire discography, to the Smithsonian, with the proviso that they always remain in print, whether or not they made a buck.

This has meant that scholars and fans of folk from all over the world have always been able to find the work of Pete Seeger, The Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, and Lead Belly, to name but a few of the label’s “stars.” There are many more: Bill Monroe, Doc Watson, Elizabeth Cotten, Reverend Gary Davis…. So many names in the pantheon of folk giants Robert Crumb immortalized in his colorful, and unusually tasteful, Heroes of Blues, Jazz, and Country. But Folkways has preserved much more besides. Kentucky’s Old Regular Baptist Church’s a capella hymns, Kilby Snow’s autoharp, Snooks English’s New Orleans street singing, Alice Gerrard and Hazel Dickens’ 60s interpretations of traditional bluegrass…. Music that appealed to small but culturally rich communities in its day, and that may have disappeared along with those communities in the scrum of cultural history, dominated as it is by mass entertainments.

The small, regional creations, some teetering on genius, some haunting in their artlessness, are critical documents of old America, the hollers, deserts, streets, swamps, low country, back country, mountains, valleys…. Hear it all in the Spotify playlist above (or access it here), 837 tracks of Folkways recordings. Smithsonian Folkways is perhaps best known for its North American artists, but it has released recordings from all over the world. Rather than creating commodities, the institution functions as a repository of global cultural memory, collecting and preserving “people’s music.” Since Asch’s endowment, Folkways has created an additional six labels under its umbrella and released over 300 new recordings. In 2003, they partnered with the American Folklife Center for the “Save Our Sounds” project, which aims to preserve recordings like those made by Thomas Edison on wax cylinders. Folkways opens a window on an alternate world where cultural production is not a perpetual struggle for ratings, reviews, and sales dominance.

It’s not entirely a utopian vision. There is the danger of a paternalizing approach. Curators like Asch, Harry Smith, John and Alan Lomax, and hundreds more serious enthusiasts and ethnographers have their own agendas, interests, biases, and blind spots. What we understand now as traditional Delta blues, for example, is a product of selection bias—it excludes many artists and varieties that didn’t catch on with collectors. Still Folkways remedies much of this shortcoming by including work from a broad spectrum of unknown composers, interpreters, and performers. There may be no form of modern folk music today that hasn’t been crafted and molded by the music industry, which might mean, by definition, that there is no modern folk music. For such a thing to exist—the “people’s music”—perhaps more democratic economies and institutions must prevail.

Related Content:

Hear 17,000+ Traditional Folk & Blues Songs Curated by the Great Musicologist Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax’s Music Archive Houses Over 17,400 Folk Recordings From 1946 to the 1990s

Legendary Folklorist Alan Lomax: ‘The Land Where the Blues Began’

Woody Guthrie at 100: Celebrate His Amazing Life with a BBC Film

Hear Zora Neale Hurston Sing the Bawdy Prison Blues Song “Uncle Bud” (1940)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness