Adobe Photoshop, the world’s best-known piece of image-editing software, has long since transitioned from noun to verb: “to Photoshop” has come to mean something like “to alter a photograph, often with intent to mislead or deceive.” But in that usage, Photoshopping didn’t begin with Photoshop, and indeed the early masters of Photoshopping did it well before anyone had even dreamed of the personal computer, let alone a means to manipulate images on one. In America, the best of them worked for the movies; in Soviet Russia they worked for a different kind of propaganda machine known as the State, not just producing official photos but going back to previous official photos and changing them to reflect the regime’s ever-shifting set of preferred alternative facts.

“Like their counterparts in Hollywood, photographic retouchers in Soviet Russia spent long hours smoothing out the blemishes of imperfect complexions, helping the camera to falsify reality,” writes David King in the introduction to his book The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia. “Stalin’s pockmarked face, in particular, demanded exceptional skills with the airbrush. But it was during the Great Purges, which raged in the late 1930s, that a new form of falsification emerged. The physical eradication of Stalin’s political opponents at the hands of the secret police was swiftly followed by their obliteration from all forms of pictorial existence.”

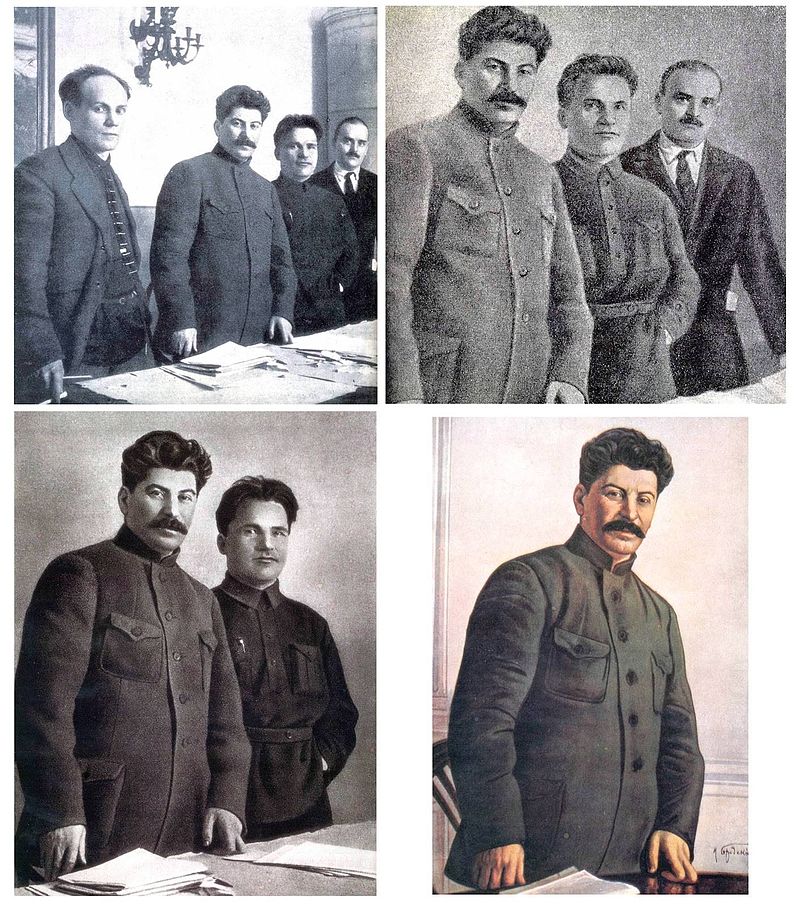

Using tools that now seem impossibly primitive, Soviet proto-Photoshoppers made “once-famous personalities vanish” and crafted photographs representing Stalin “as the only true friend, comrade, and successor to Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and founder of the USSR.”

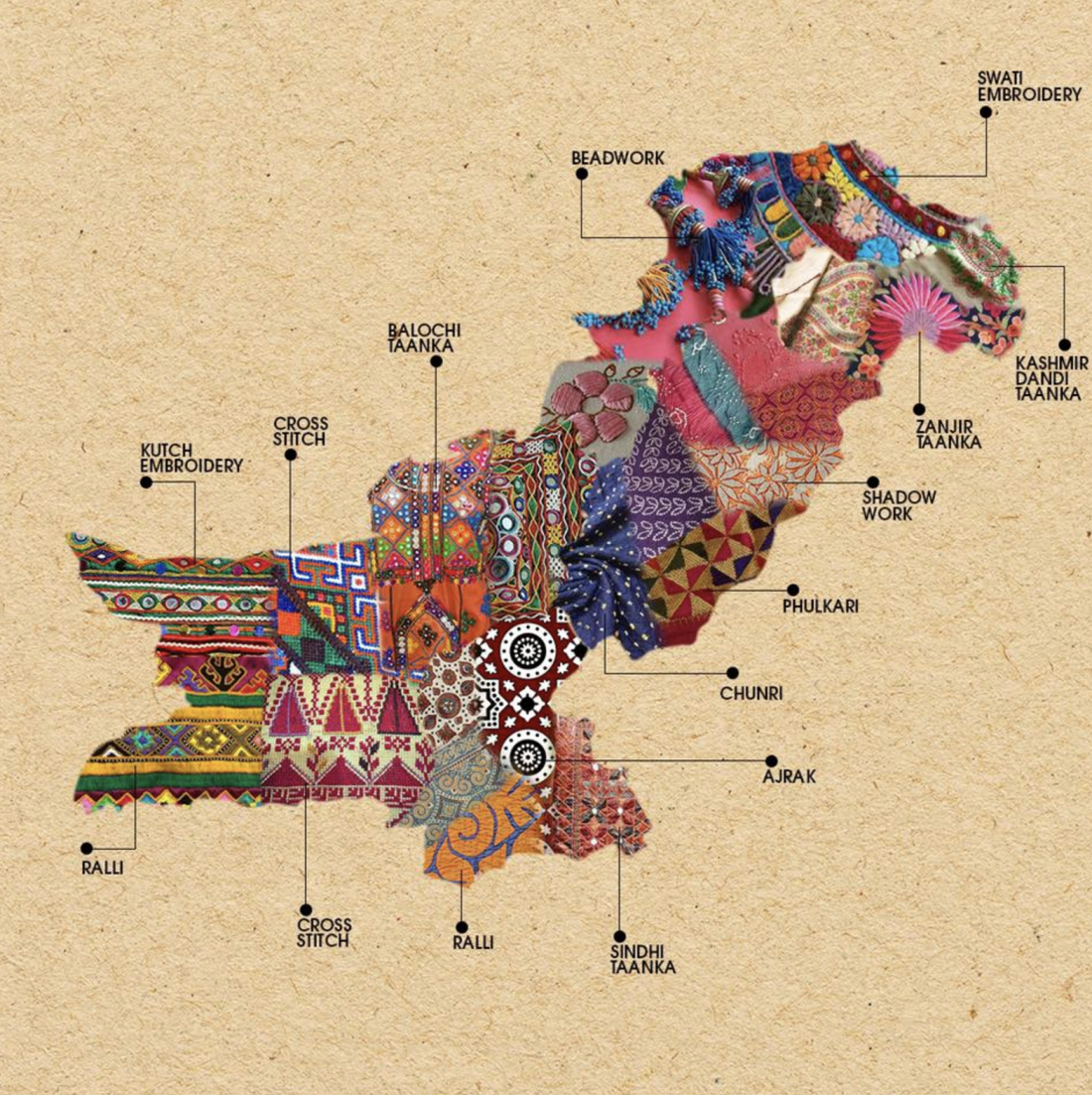

This quasi-artisanal work, “one of the more enjoyable tasks for the art department of publishing houses during those times,” demanded serious dexterity with the scalpel, glue, paint, and airbrush. (Some examples, as you can see in this five-page gallery of images from The Commissar Vanishes, evidenced more dexterity than others.) In this manner, Stalin could order written out of history such comrades he ultimately deemed disloyal (and who usually wound up executed as) as Naval Commissar Nikolai Yezhov, infamously made to disappear from Stalin’s side on a photo taken alongside the Moscow Canal, or People’s Commissar for Posts and Telegraphs Nikolai Antipov, commander of the Leningrad party Sergei Kirov, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Nikolai Shvernik — pictured, and removed one by one, just above.

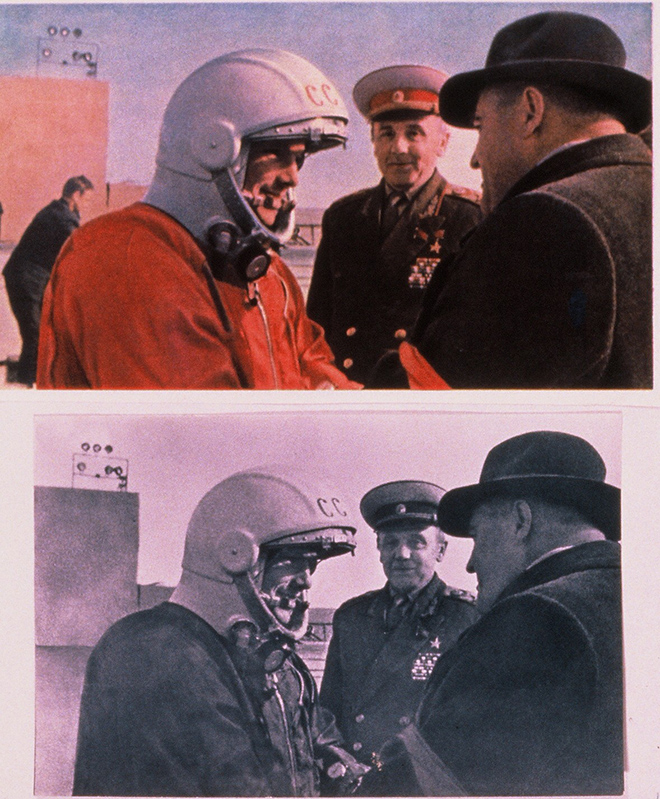

This practice even extended to the materials of the Soviet space program, writes Wired’s James Oberg. Cosmonauts temporarily erased from history include Valentin Bondarenko, who died in a fire during a training exercise, and the especially promising Grigoriy Nelyubov (pictured, and then not pictured, at the top of the post), who “had been expelled from the program for misbehavior and later killed himself.” Yuri Gagarin, the cosmonaut who made history as the first human in outer space, did not, of course, get erased by the proud authorities, but even his photos, like the one just above where he shakes hands with the Soviet space program’s top-secret leader Sergey Korolyov, went under the knife for cosmetic reasons, here the removal of the evidently distracting workman in the background — hardly a major historical figure, let alone a controversial one, but still a real and maybe even living reminder that while the camera may lie, it can’t hold its tongue forever.

Related Content:

Joseph Stalin, a Lifelong Editor, Wielded a Big, Blue, Dangerous Pencil

Leon Trotsky: Love, Death and Exile in Mexico

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.