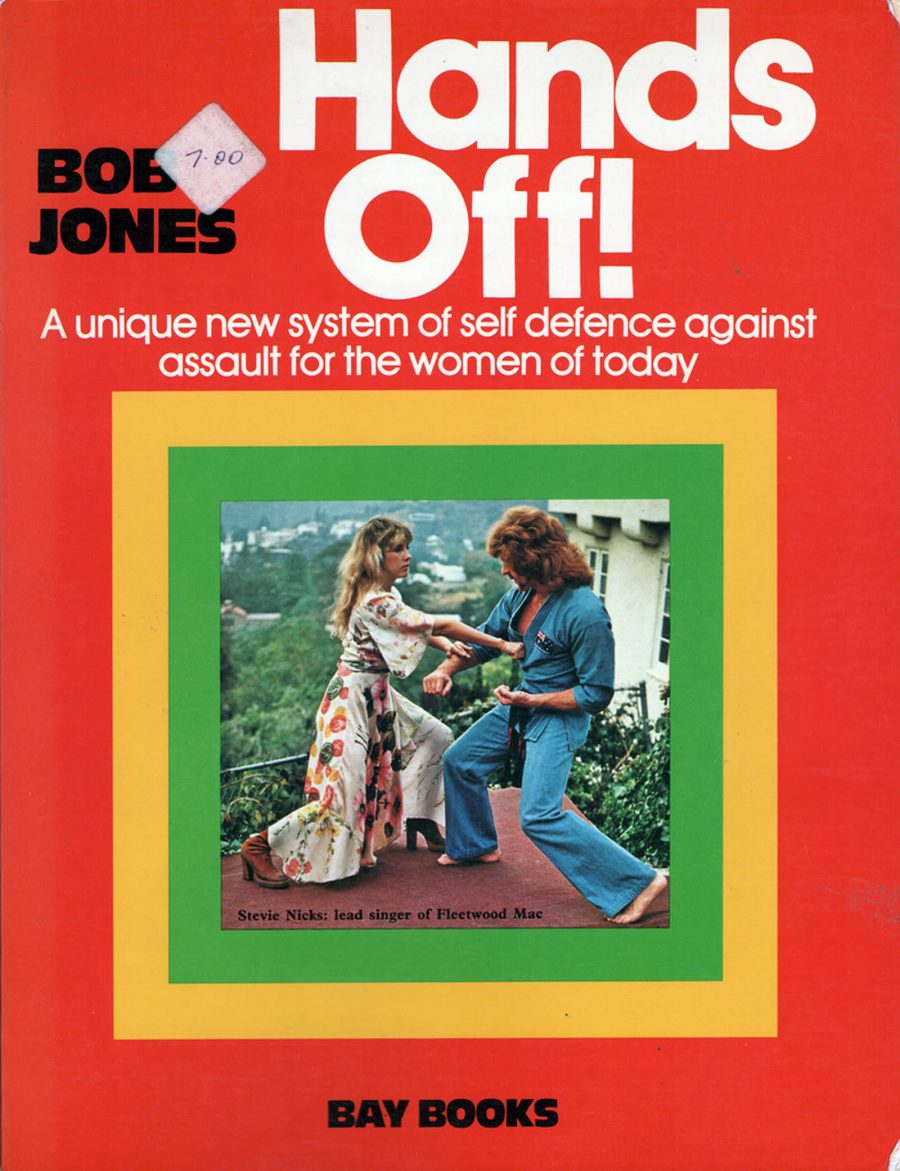

Yesterday, on Twitter, Priscilla Page reminded us of the time when “Stevie Nicks showed us how to kick ass in high-heeled boots in her bodyguard’s self-defense book,” calling our attention to the little-known 1983 book, Hands Off!: A Unique New System of Self Defence Against Assault for the Women of Today.

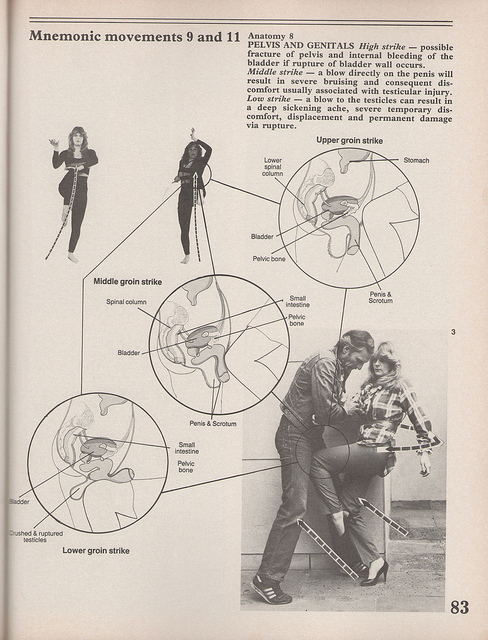

The book itself was written by Bob Jones, an Australian martial arts instructor who doubled as a security guard for Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Joe Cocker and other stars. And it featured what Jones called “mnemonic movements”–essentially a series of nine subconscious/reflexive self-defense moves (like a swift knee to the groin). See Jones’ website for a more complete explanation of the exercise routine that also provided, he notes, a great cardio workout.

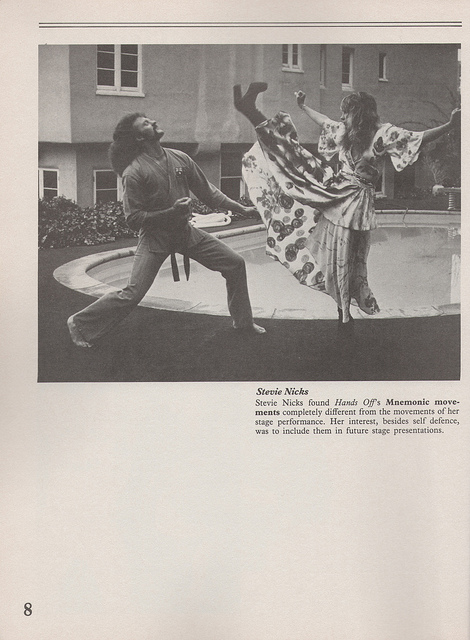

Stevie Nicks agreed to take part in a photoshoot where she would help demonstrate the nine mnemonic movements. Jones recalls,” This lady was a professional: in two hours I had a hundred of the most magnificent photos ever offered to the martial arts, and just one would make the cover [above].”

“On this day of the shoot I was standing in my martial arts training uniform, wearing my Black Belt. Then Stevie appeared, her hair done to resemble the mane of a lion. She was psyched up for some serious photographing. Stevie wore her familiar thick-soled, thick-heeled, knee-high brown suede kid leather boots. High roll-over socks appeared over the top of these elegant Swedish boots and hung tentatively around her knees.” “In these kicking-style photographs the sun also made her dress partially see-through: just enough to be artistically interesting.”

Hands Off is now long out of print. But you can find a series of images from the book on the Voices of East Anglia and Dangerous Minds websites.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Radical French Philosophy Meets Kung-Fu Cinema in Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973)

Kung Fu & Martial Arts Movies Online