“Ghost in the Shell is not in any sense an animated film for children,” wrote Roger Ebert twenty years ago. “Filled with sex, violence and nudity (although all rather stylized), it’s another example of anime, animation from Japan aimed at adults.” Now, when no critic any longer needs to explain the term anime to Western readers, we look back on Ghost in the Shell (1995) as one of the true masterpieces among Japanese animated feature films, mature not just in its content but in its form. Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, takes a look at how it expresses its philosophical themes through its still-striking cyberpunk setting in his video essay “Identity in Space.”

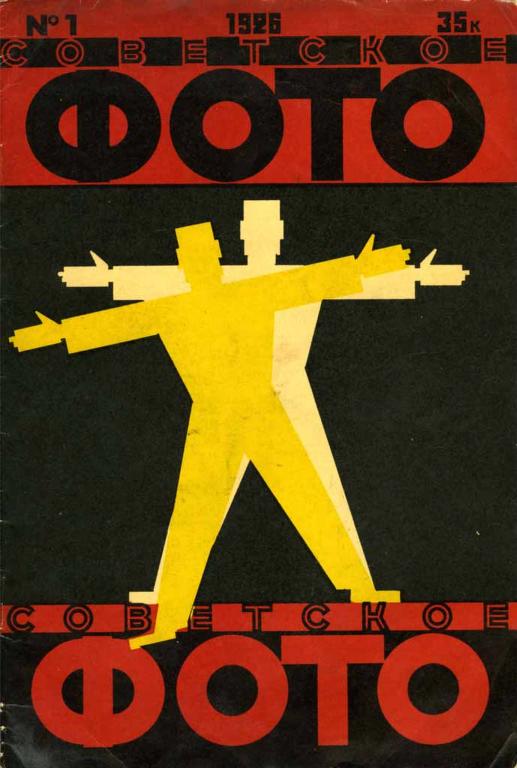

Puschak first highlights the presence (in the middle of this “sci-fi action thriller” about the hunt for a wanted hacker turned self-aware artificial intelligence) of an action-free interlude: a “three minute and twenty-ish second-long scene” consisting of nothing but “34 gorgeous, exquisitely detailed atmospheric shots of a future city in Japan that’s modeled after Hong Kong.”

Its plot-suspending visual exploration of the film’s Blade Runner-esque urban space of “a chaotic multicultural future city dominated by the intersections of old and new structures, connected by roads, canals, and technology,” emphasizes that “spaces, like identities, are constructed. Though space often feels neutral or given, like we could move anywhere within it, our movements, our activities, our life, is always limited by the way space is produced.”

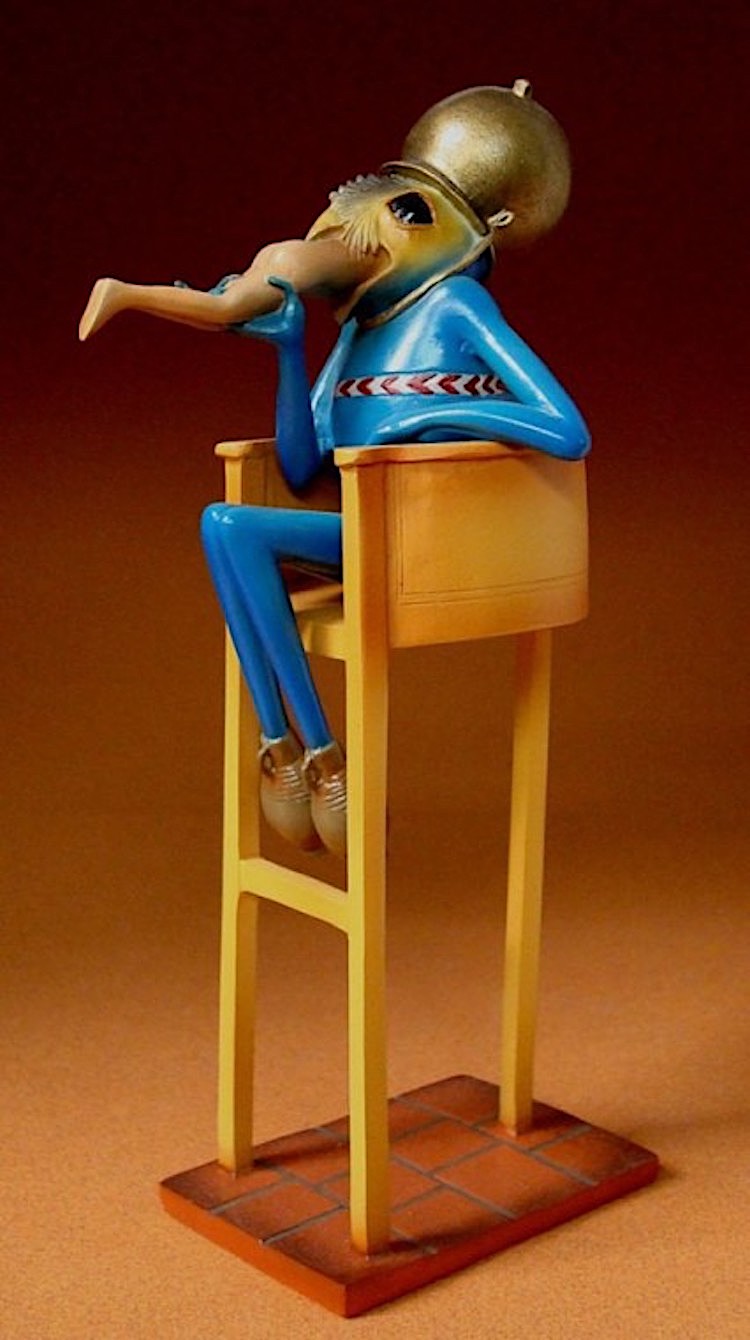

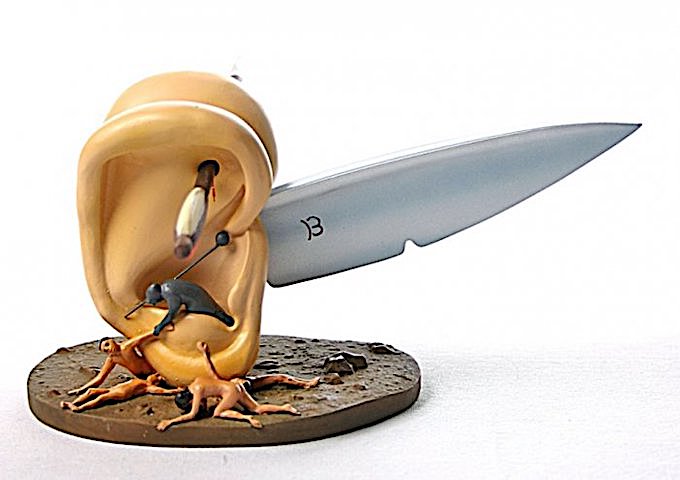

Just as all of Ghost in the Shell’s characters exist in space, the main ones also exist in cybernetic bodies, regarding their identities as stored in their effectively transplantable brains all connected over a vast information network. The half-hour-long analysis from AnimeEveryday just above gets into the philosophical dilemma this presents to the film’s protagonist, the cyborg police officer Motoko Kusanagi, examining in depth several of the scenes that — through dialogue, imagery, symbolism, or subtle combinations of the three that viewers might not catch the first time around — illuminate the story’s central questions about the nature of man, the nature of machine, and the nature of what emerges when the two intersect.

Film Herald’s briefer explanation of Ghost in the Shell (which contains potentially NSFW images) points to three main themes: identity, Cartesian dualism, and evolution, all concepts that come into question — or at least demand a thorough revision — when the boundary between the natural and the synthetic blurs to the film’s imagined extent. “My intuition told me that this story about a futuristic world carried an immediate message for our present world,” said director Mamoru Oshii, and now, more than two decades later, Hollywood has even got around to remaking it in a live-action version starring Scarlett Johansson in the Kusanagi role. That does provides a chance to update some of the now-dated-looking technology seen in the animated original, but there’s no improving on its artistry.

Related Content:

Blade Runner Spoofed in Three Japanese Commercials (and Generally Loved in Japan)

Early Japanese Animations: The Origins of Anime (1917–1931)

How the Films of Hayao Miyazaki Work Their Animated Magic, Explained in 4 Video Essays

The Matrix: What Went Into The Mix

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.