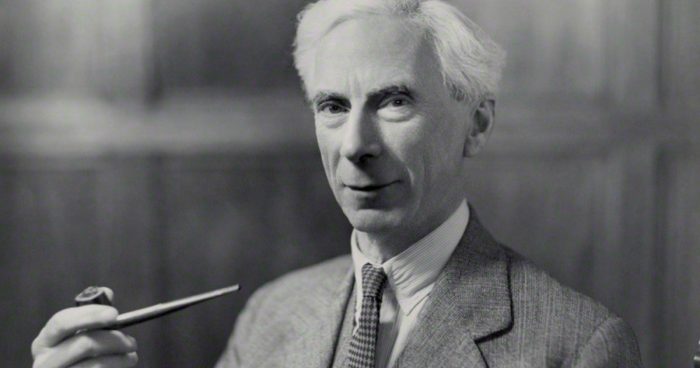

Image by National Portrait Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons

Changing the minds of others has never counted among humanity’s easiest tasks, and it seems only to have become an ever-stiffer challenge as history has ground along. Increasingly many, as Yale professor David Bromwich recently argued in the London Review of Books, “have had no practice in using words to influence people unlike themselves. That is an art that can be lost. It depends on a quantum of accidental communication that is missing in a life of organised contacts.” We might find ourselves in reasonably fruitful debates with basically like-minded friends, acquaintances, and strangers on the internet, but can we ever convince, or be convinced by, someone truly different from us?

Bertrand Russell doubted it. In 1962, long before the structures of the internet allowed us to build tighter echo chambers than ever before, the Nobel-winning philosopher “received a series of letters from an unlikely correspondent — Sir Oswald Mosley, who had founded the British Union of Fascists thirty years earlier,” writes Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova.

“Mosley was inviting — or, rather, provoking — Russell to engage in a debate, in which he could persuade the moral philosopher of the merits of fascism.” Even at the age of 89, with little time and much else to do, Russell declined with the utmost force and clarity in a piece of correspondence featured on Letters of Note:

Dear Sir Oswald,

Thank you for your letter and for your enclosures. I have given some thought to our recent correspondence. It is always difficult to decide on how to respond to people whose ethos is so alien and, in fact, repellent to one’s own. It is not that I take exception to the general points made by you but that every ounce of my energy has been devoted to an active opposition to cruel bigotry, compulsive violence, and the sadistic persecution which has characterised the philosophy and practice of fascism.

I feel obliged to say that the emotional universes we inhabit are so distinct, and in deepest ways opposed, that nothing fruitful or sincere could ever emerge from association between us.

I should like you to understand the intensity of this conviction on my part. It is not out of any attempt to be rude that I say this but because of all that I value in human experience and human achievement.

Yours sincerely,

Bertrand Russell

Russell passed on eight years later, in 1970, and Mosley a decade thereafter. “His final message to the British people appeared in a letter to the New Statesman written only a week earlier,” remembers journalist Hugh Purcell in that newspaper. It concerned an article’s description of the “Olympia rally,” the 1934 debacle that lost the British Union of Fascists much of what public support it enjoyed. “The largest audience ever seen at that time assembled to fill the Olympia hall and hear the speech,” Mosley insisted. “A small minority determined by continuous shouting to prevent my speech being heard. After due warning our stewards removed with their bare hands men among whom were some armed with such weapons as razors and knives. The audience were then able to listen to a speech which lasted for nearly two hours.”

The New Statesmen, printing Mosley’s letter posthumously, ran it under this introduction: “Throughout his life he was intent on persuading people that their view of history was mistaken.” Despite his unceasing efforts, he ultimately persuaded few — and it would hardly have required as keen an observer as Russell to see that someone like Mosley certainly wasn’t about to let himself be persuaded by anyone else.

via Letters of Note/Brain Pickings and The Bertrand Russell Archives, McMaster University Library

Related Content:

Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy

Listen to ‘Why I Am Not a Christian,’ Bertrand Russell’s Powerful Critique of Religion (1927)

Bertrand Russell and F.C. Copleston Debate the Existence of God, 1948

Face to Face with Bertrand Russell: ‘Love is Wise, Hatred is Foolish’

How Bertrand Russell Turned The Beatles Against the Vietnam War

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.