In 1968, both Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated, and U.S. cities erupted in riots; anti-war demonstrators chanted “the whole world is watching” as police beat and tear-gassed them in Chicago outside the Democratic convention. George Wallace led a popular political movement of Klan sympathizers and White Citizens Councils in a vicious backlash against the gains of the Civil Rights movement; and the vengeful, paranoid Richard Nixon was elected president and began to intensify the war in Vietnam and pursue his program of harassment and imprisonment of black Americans and anti-war activists through Hoover’s FBI (and later the bogus “war on drugs”).

Good times, and given several pertinent similarities to our current moment, it seems like a year to revisit if we want to see recent examples of organized, determined resistance by a very beleaguered Left. We might look to the Black Panthers, the Yippies, or Students for a Democratic Society, to name a few prominent and occasionally affiliated groups. But we can also revisit a near-revolution across the ocean, when French students and workers took to the Paris streets and almost provoked a civil war against the government of authoritarian president Charles de Gaulle. The events often referred to simply as Mai 68 have haunted French conservatives ever since, such that president Nicolas Sarkozy forty years later claimed their memory “must be liquidated.”

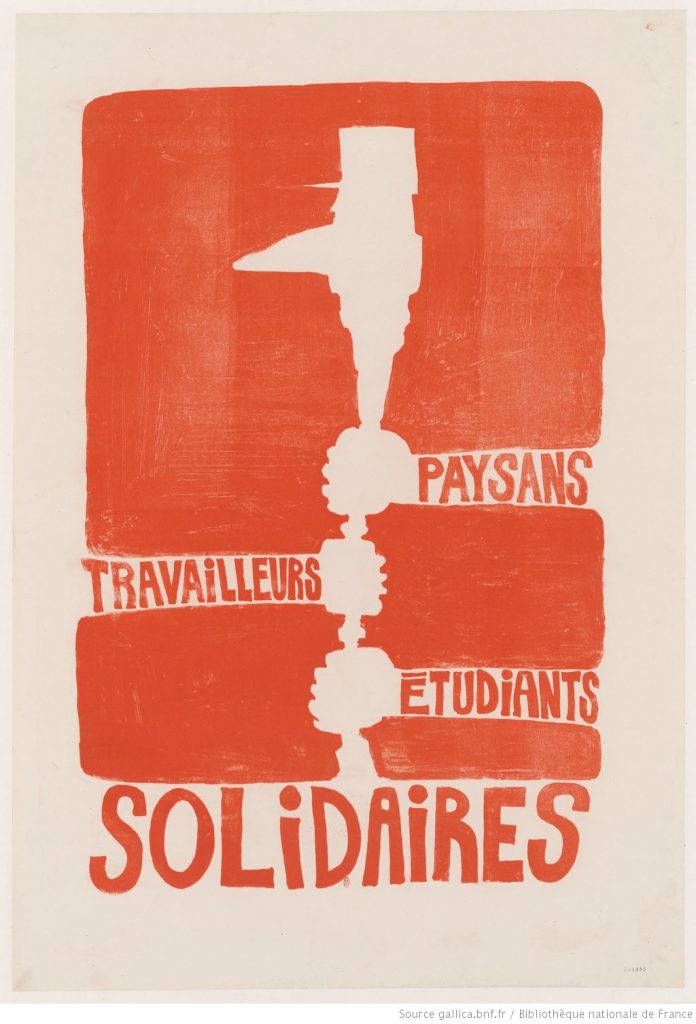

May 1968, wrote Steven Erlanger on the 40th anniversary, was “a holy moment of liberation for many, when youth coalesced, the workers listened and the semi-royal French government of de Gaulle took fright.” As loose coalitions in the U.S. pushed back against their government on multiple fronts, the Paris uprising (“revolution” or “riot,” depending on who writes the history) brought together several groups in common purpose who would have otherwise never have broken bread: “a crazy array of leftist groups,” students, and ordinary working people, writes Peter Steinfels, including “revisionist socialists, Trotskyists, Maoists, anarchists, surrealists and Marxists. They were anticommunist as much as anticapitalist. Some appeared anti-industrial, anti-institutional, even anti-rational.”

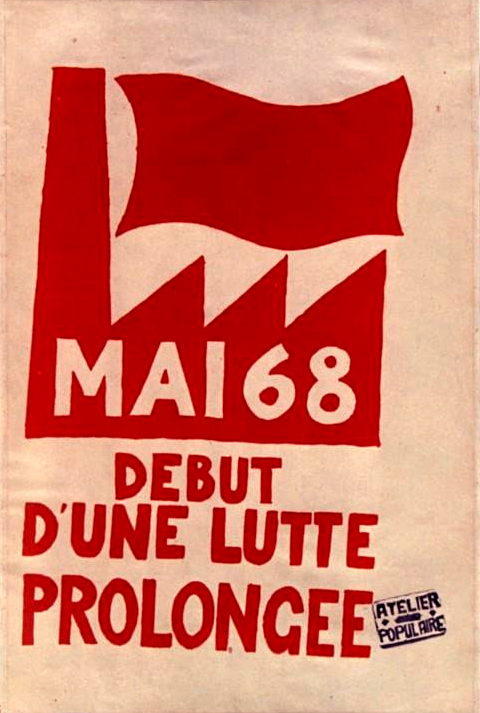

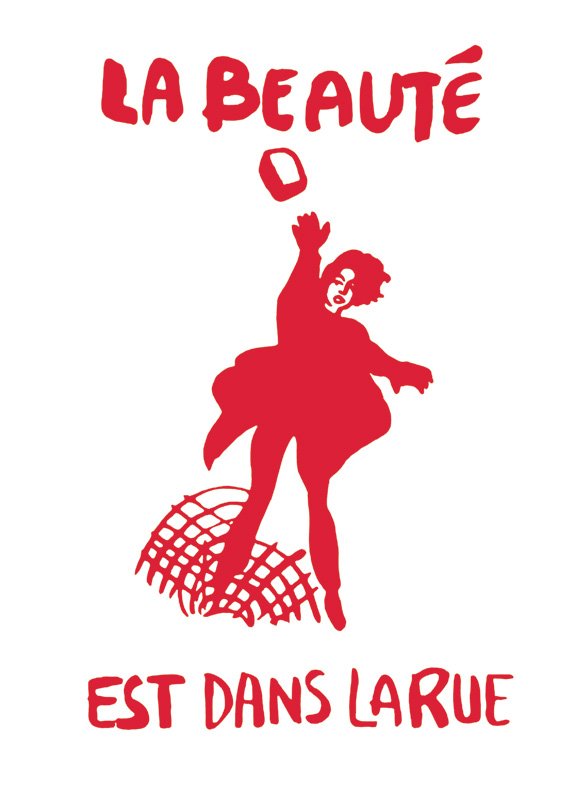

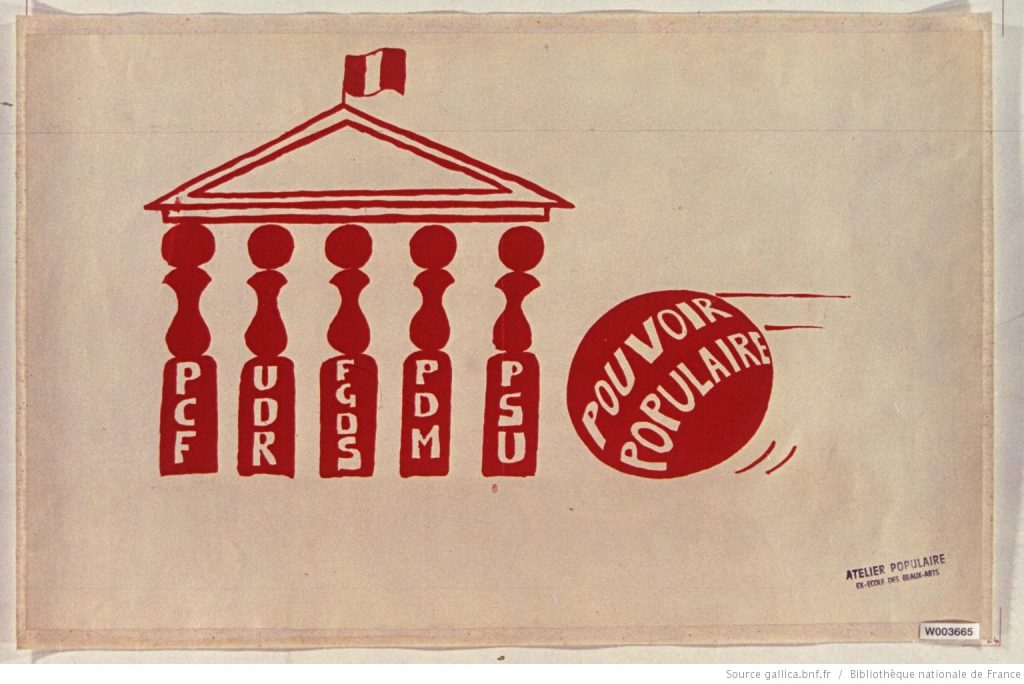

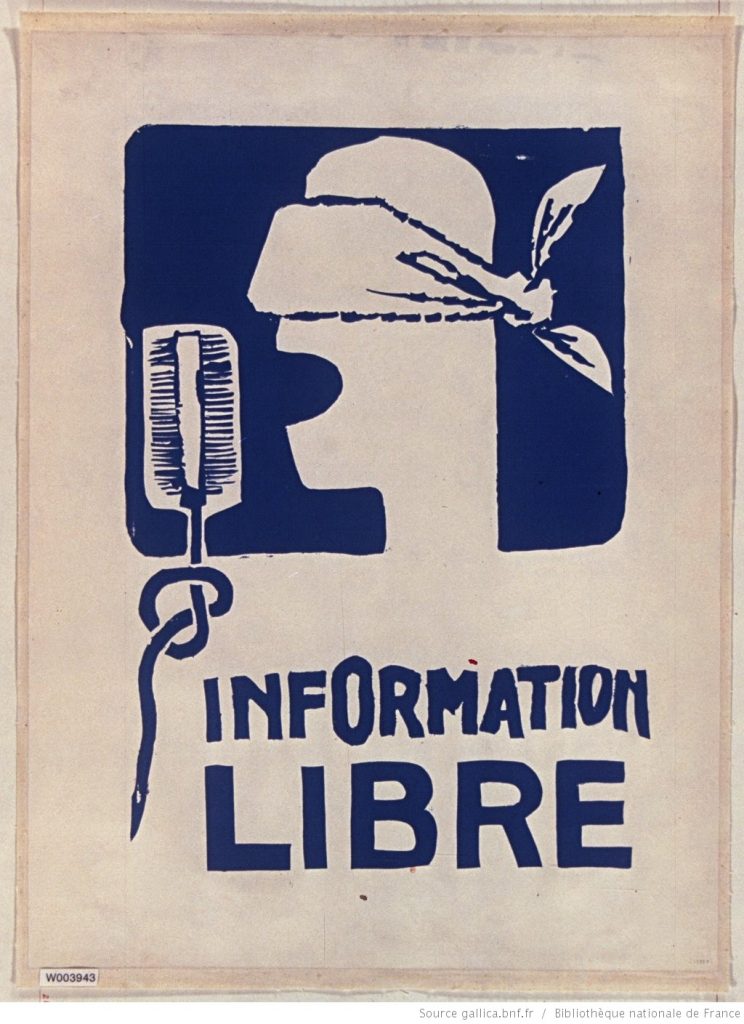

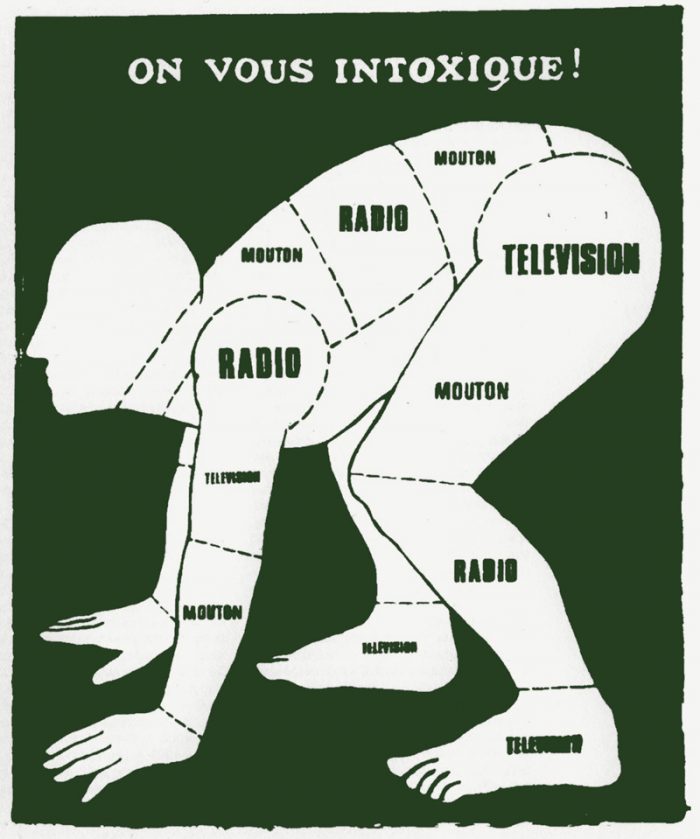

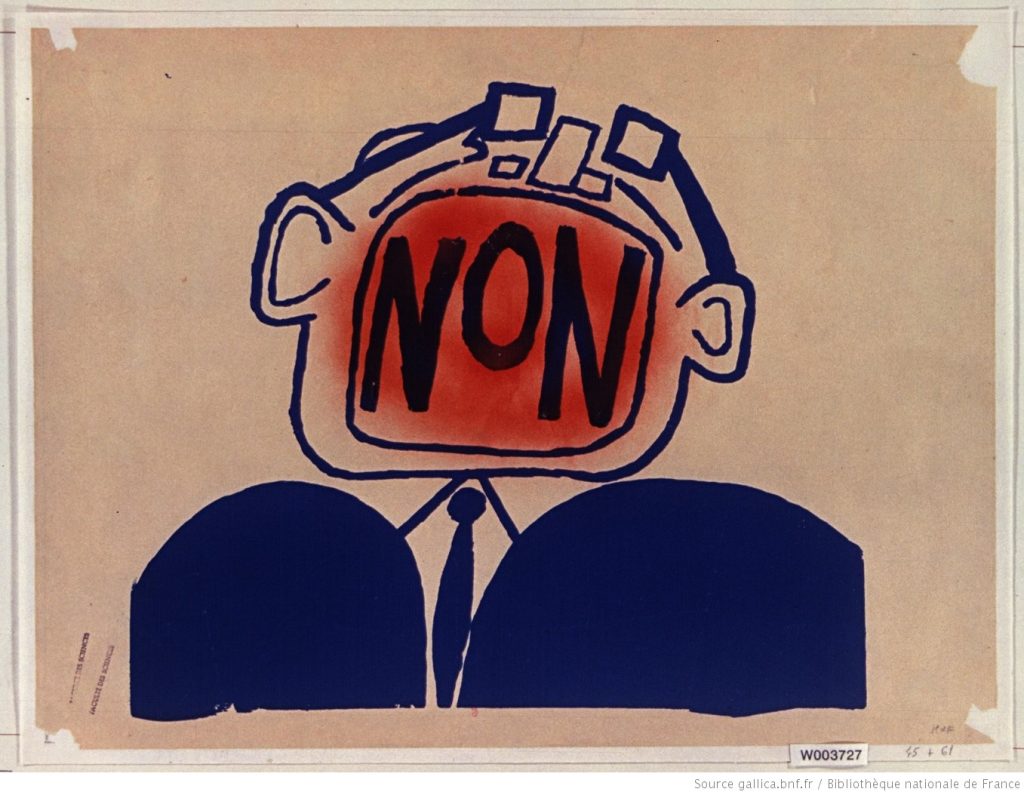

“Be realistic: Demand the impossible!” was one of the May movement’s slogans. A great many more slogans and icons appeared on “extremely fine examples of polemical poster art” like those you see here. These come to us via Dangerous Minds, who explain:

The Atelier Populaire, run by Marxist artists and art students, occupied the École des Beaux-Arts and dedicated its efforts to producing thousands of silk-screened posters using bold, iconic imagery and slogans as well as explicitly collective/anonymous authorship. Most of the posters were printed on newssheet using a single color with basic icons such as the factory to represent labor and a fist to stand for resistance.

The Paris uprisings began with university students, protesting same-sex dorms and demanding educational reform, “the release of arrested students and the reopening of the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris,” notes the Global Nonviolent Action Database. But in the following weeks the “protests escalated and gained more popular support, because of continuing police brutality.” Among the accumulating democratic demands and labor protests, writes Steinfels, was “one great fear… that contemporary capitalism was capable of absorbing any and all critical ideas or movements and bending them to its own advantage. Hence, the need for provocative shock tactics.”

This fear was dramatized by Situationists, who—like Yippies in the States—generally preferred absurdist street theater to earnest political action. And it provided the thesis of one of the most radical texts to come out of the tumultuous times, Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. In a historical irony that would have Debord “spinning in his grave,” the Situationist theorist has himself been co-opted, recognized as a “national treasure” by the French government, writes Andrew Gallix, and yet, “no one—not even his sworn ideological enemies—can deny Debord’s importance.”

The same could be said for Michel Foucault, who found the events of May ’68 transformational. Foucault pronounced himself “tremendously impressed” with students willing to be beaten and jailed, and his “turn to political militancy within a post-1968 horizon was the chief catalyst for halting and then redirecting his theoretical work,” argues professor of philosophy Bernard Gendron, eventually “leading to the publication of Discipline and Punish,” his groundbreaking “genealogy” of imprisonment and surveillance.

Many more prominent theorists and intellectuals took part and found inspiration in the movement, including André Glucksmann, who recalled May 1968 as “a moment, either sublime or detested, that we want to commemorate or bury.… a ‘cadaver,’ from which everyone wants to rob a piece.” His comments sum up the general cynicism and ambivalence of many on the French left when it comes to May ’68: “The hope was to change the world,” he says, “but it was inevitably incomplete, and the institutions of the state are untouched.” Both student and labor groups still managed to push through several significant reforms and win many government concessions before police and de Gaulle supporters rose up in the thousands and quelled the uprising (further evidence, Anne-Elisabeth Moutet argued this month, that “authoritarianism is the norm in France”).

The iconic posters here represent what Steinfels calls the movement’s “utopian impulse,” one however that “did not aim at human perfectibility but only at imagining that life could really be different and a whole lot better.” These images were collected in 2008 for a London exhibition titled “May 68: street Posters from the Paris Rebellion,” and they’ve been published in book form in Beauty is in the Street: A Visual Record of the May ’68 Paris Uprising. (You can also find and download many posters in the digital collection hosted by the Bibliotheque nationale de France.)

Perhaps the co-option Debord predicted was as inevitable as he feared. But like many radical U.S. movements in the sixties, the coordinated mobilization of huge numbers of people from every strata of French society during those exhilarating and dangerous few weeks opened a window on the possible. Despite its short-lived nature, May 1968 irrevocably altered French civil society and intellectual culture. As Jean-Paul Sartre said of the movement, “What’s important is that the action took place, when everybody believed it to be unthinkable. If it took place this time, it can happen again.”

via Dangerous Minds/Messy N Chic

Related Content:

Striking Posters From Occupy Wall Street: Download Them for Free

Bed Peace Revisits John Lennon & Yoko Ono’s Famous Anti-Vietnam Protests

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness