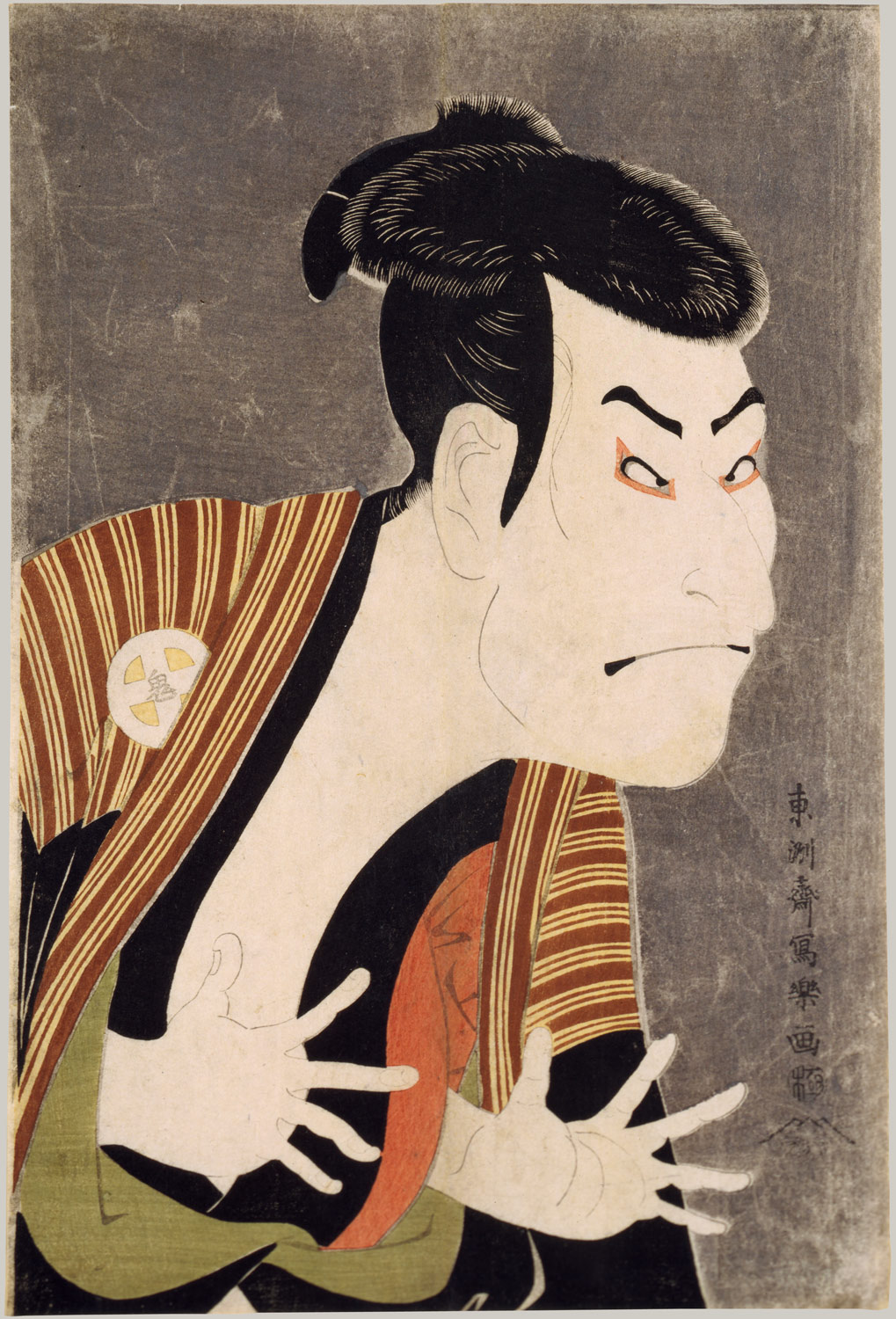

“Kabuki,” as a cultural reference, has traveled astonishingly far beyond the early seventeenth-century Japan in which the form of kabuki theatre originated. Even 21st-century Westerners are quick to use the word when describing anything elaborately performative or melodramatic: in the negative sense, it criticizes an excessive artificiality; in the positive one, it praises complex, nuance-laden mastery. Many scholars of kabuki will disagree about when, exactly, kabuki had its heyday, but none would doubt the immortality, for a kabuki actor of the late eighteenth century, granted by a Sharaku portrait.

Also known to us as Tōshūsai Sharaku (probably not his real name), Sharaku worked in the form of yakusha‑e woodblock prints, a kind of ukiyo-e focusing on actors, but only for a scant ten months in 1794 and 1795, and not always to a warm public reception.

“Renowned for creating visually bold prints that gave rare revealing glimpses into the world of kabuki,” says the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “he was not only able to capture the essential qualities of kabuki characters, but his prints also reveal, often with unflattering realism, the personalities of the actors who were famous for performing them.” Breaking somewhat from ukiyo‑e portraitist tradition, “Sharaku did not idealize his subjects or attempt to portray them realistically. Rather, he exaggerated facial features and strove for psychological realism.”

Nobody knows much about this mysterious artist’s background or his life after yakusha‑e. During it, he designed over 140 prints, and potentially many more, given the number that remain unverifiable as his work. Though he did occasional portraits of sumo wrestlers and warriors, the majority of his portraits depict actors, and seldom in an idealized fashion.

That sense of heightened reality also brought with it a certain vitality to that point unseen in yakusha‑e; art historian Muneshige Narazaki wrote that Sharaku could, within a single print of a kabuki actor or scene, depict “two or three levels of character revealed in the single moment of action forming the climax to a scene or performance.”

At the top of the post, we have three prints from the fourth and final period of Sharaku’s short career: Ichikawa Ebizō as Kudō Saemon Suketsune, Ichikawa Danjūrō VI as Soga no Gorō Tokimune, and Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Satsuma Gengobei. Below that, from top to bottom, appear Ōtani Oniji III in the Role of the Servant Edobei, Segawa Kikujurō III as Oshizu, Wife of Tanabe (one of the many female roles played without exception by male actors after the kabuki theatre attained its current form), Nakamura Nakazō II as the farmer Tsuchizō, actually Prince Koretaka, and Arashi Ryūzō I as Ishibe Kinkichi, which set an auction record for an ukiyo‑e print by selling for €389,000 at Piasa in 2009.

If you want to learn a little more about kabuki theatre itself, have a look at TED-Ed’s four-minute primer on its history. Though many of us may now regard kabuki as a high classical art form, it began as a “people’s” version of the aristocratic noh theatre, and an avant-garde one at that. Its very name appears to derive from the Japanese verb kabuku, which means “to lean” or “to be out of the ordinary.” Sharaku must have seen how incisively this theatre of the unusual, already long established by this day, could present the elements of real life; did he consider it his mission, during his woodblock-designing stint, to bring the elements of real life into its portraiture?

Related Content:

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.