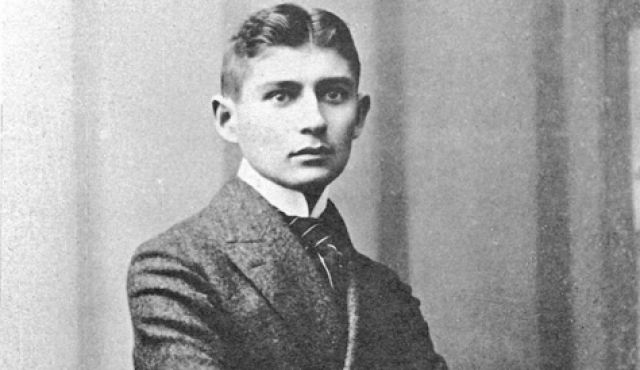

Whatever else we take from it, Franz Kafka’s nightmarish fable The Metamorphosis offers readers an especially anguished allegory on troubled sleep. Filled with references to sleep, dreams, and beds, the story begins when Gregor Samsa awakens to find himself (in David Wylie’s translation) “transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin.” After several desperate attempts to roll off his back, Gregor begins to agonize, of all things, over his stressful working hours: “’Getting up early all the time,’ he thought, ‘it makes you stupid. You’ve got to get enough sleep.” Realizing that he has overslept and missed his five o’clock train, he agonizes anew over the frantic workday ahead, and we can hear in his thoughts the complaints of their author. “Sleep and lack thereof,” writes The Independent’s Christopher Hooten, “is of course a central theme in Kafka’s best known work…. It seems there was a strong dose of autobiography at play.”

Chronically insomniac, Kafka wrote at night, then rose early each morning for his hated job at an insurance office. Though he made good use of restlessness, Kafka characterized his insomnia as much more than an inconvenient physical ailment. He thought of it in metaphysical terms, as a kind of soul-sickness. “Sleep,” he wrote in his diaries, “is the most innocent creature there is and sleepless man the most guilty.”

Insomnia transformed Kafka into an unclean thing, quivering in fear of death. “Perhaps I am afraid that the soul, which in sleep leaves me, will not be able to return,” he confessed in a letter to German writer Milena Jesenská. Anxious expressions like this, writes Theresa Fisher, have led researchers to “speculate that Kafka’s pathological traits… indicate borderline personality disorder.” This posthumous diagnosis may be a leap too far. “Unearthing his insomnia, however,” and its effects on his life and work, “requires less speculation.”

Kafka’s descriptions of his anxious insomniac writing habits have led Italian doctor Antonio Perciaccante and his wife and co-author Alessia Coralli to argue in a recent paper published in The Lancet that the writer composed much of his fiction in a state of something like lucid dreaming. In one diary entry, Kafka writes, “it was the power of my dreams, shining forth into wakefulness even before I fall asleep, which did not let me sleep.” Perciaccante and Coralli note that “this seems to be a clear description of a hypnagogic hallucination, a vivid visual hallucination experienced just before the sleep onset.” It’s something we’ve all experienced. Kafka, fearing sleep, stayed there as long as he could. Lest we think of his writing as therapeutic in some way, he gives no indication that it was so. Indeed, it seems that writing introduced more pain: “When I don’t write,” he told Jesenská, “I am merely tired, sad, heavy; when I do write, I am torn by fear and anxiety.”

Kafka made many similar statements about sleep deprivation bringing him to “a depth almost inaccessible at normal conditions.” The visions he encountered, he wrote, “shape themselves into literature.” Through surveying the literature, biographies, interpretations, and the author’s diaries and letters to Jesenská and Felice Bauer, Perciaccante and Coralli pieced together a “psychophysiological” account of Kafka’s dream logic. As Perciaccante told ResearchGate in an interview, his study concerned itself less with the causes of Kafka’s sleeplessness. He admits “it’s difficult to classify Kafka’s insomnia.” Instead the authors concerned themselves with the effects of remaining in a hypnagogic state (a word, notes Drake Baer, that etymologically means “being abducted into sleep”), as well as Kafka’s awareness of his insomnia’s magical and debilitating power.

Metamorphosis, says Perciaccante, in addition to a work about social and familial alienation, “may also represent a metaphor for the negative effects that poor quality sleep, short sleep duration, and insomnia may have on mental and physical health.” Had Kafka overcome his malady, he may never have written his best-known work. Indeed, he may not have written at all. “Perhaps there are other forms of writing,” he told Max Brod in 1922, “but I know only this kind, when fear keeps me from sleeping, I know only this kind.” Perciaccante and Coralli see Kafka’s insomniac torment as a primary theme in his work, but two dissenting voices, writer Saudamini Deo and forensic doctor and anthropologist Philippe Charlier, disagree. Writing into The Lancet to express their view, they assert that despite Kafka’s persistent laments and the squirmy fate of the autobiographical Gregor Samsa, the writer’s “insomnia was not at all dehumanizing… but the exact opposite—ie, humanizing the self by bringing to surface elements of unconscious that guide most actions of our waking life.”

Related Content:

Franz Kafka’s Kafkaesque Love Letters

How a Good Night’s Sleep — and a Bad Night’s Sleep — Can Enhance Your Creativity

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

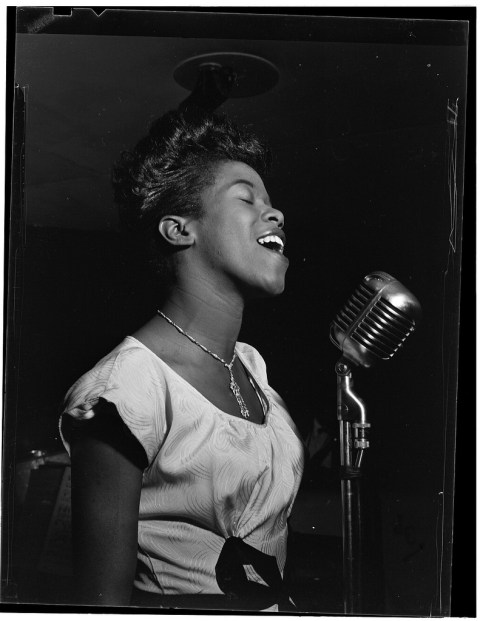

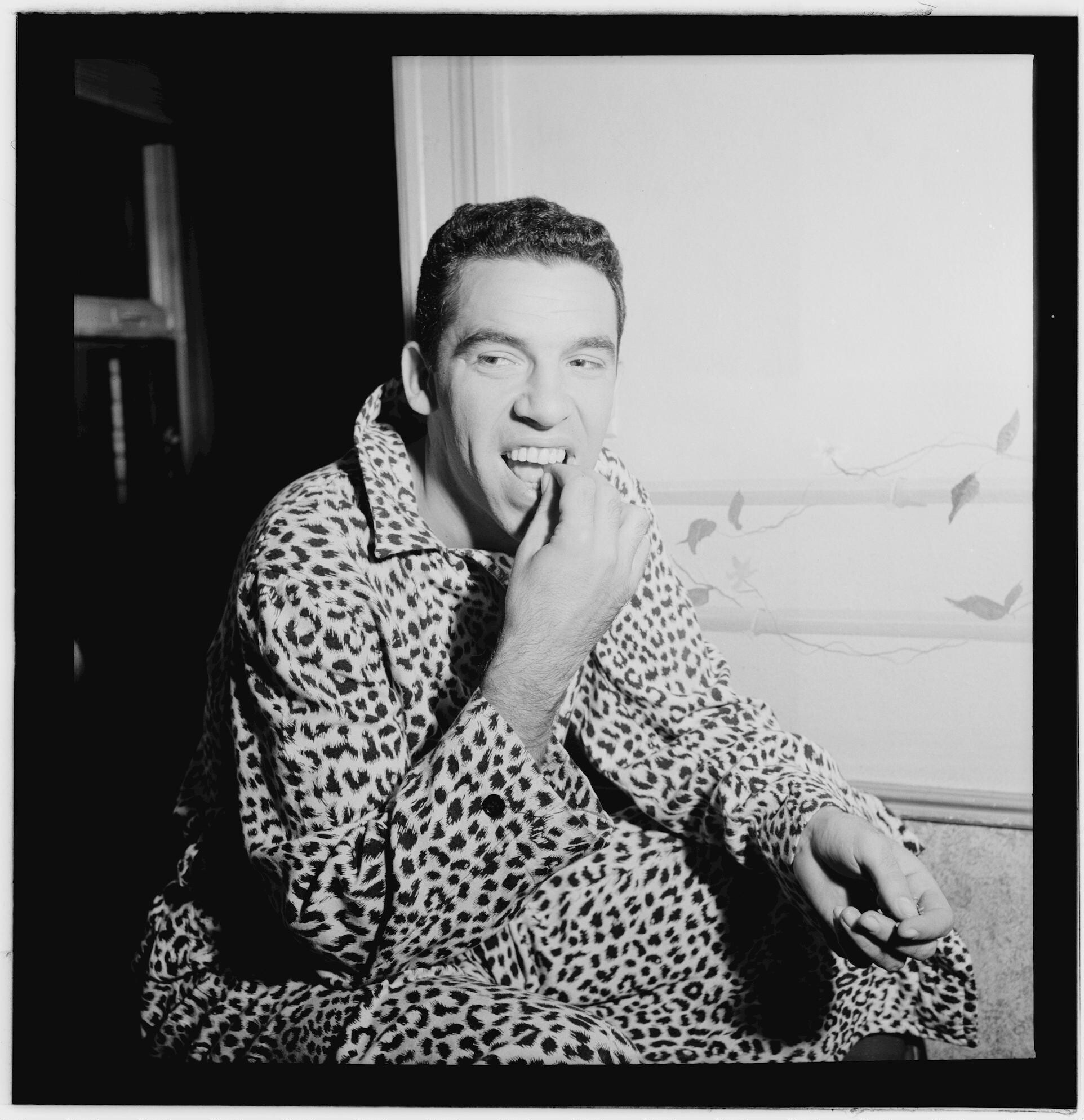

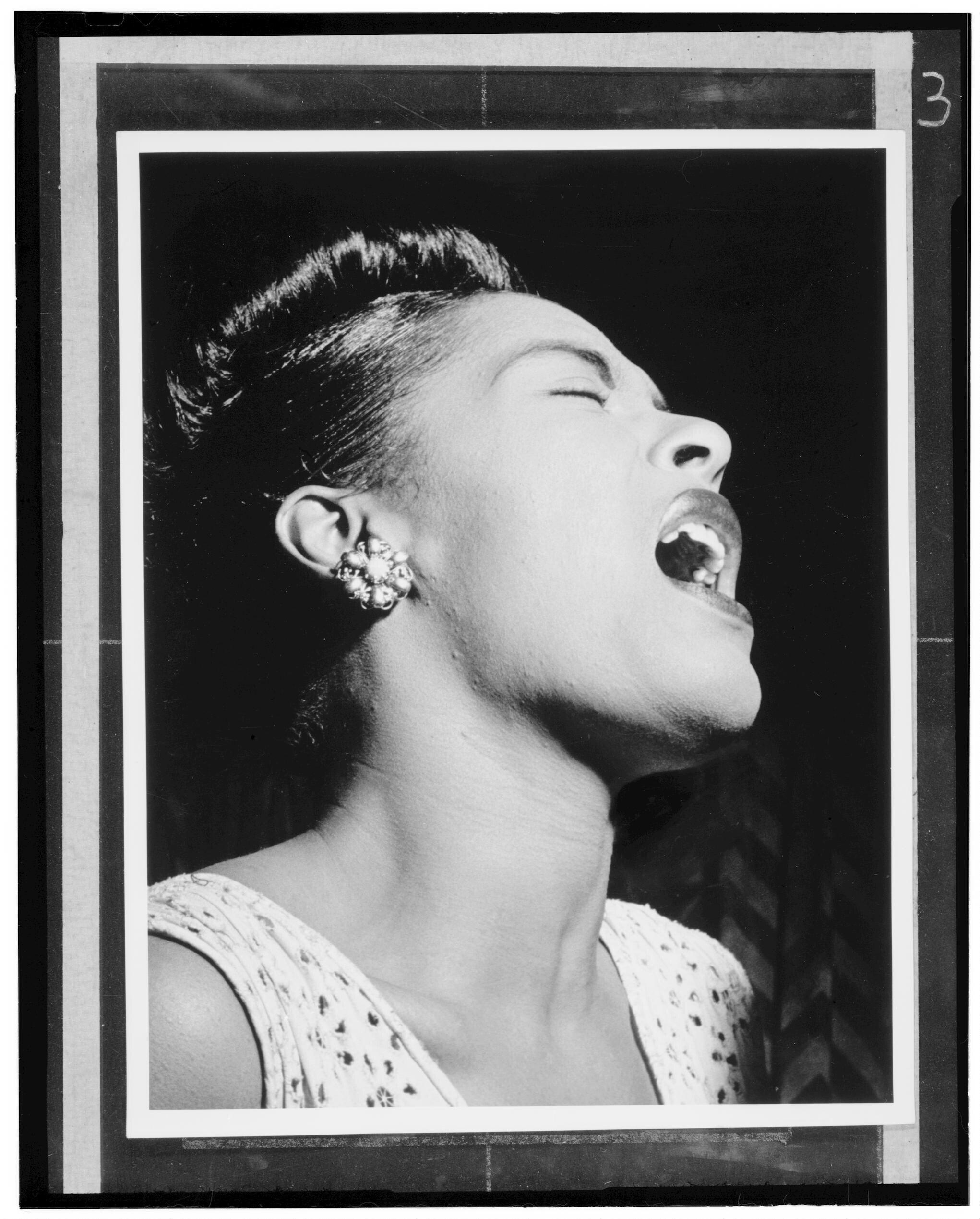

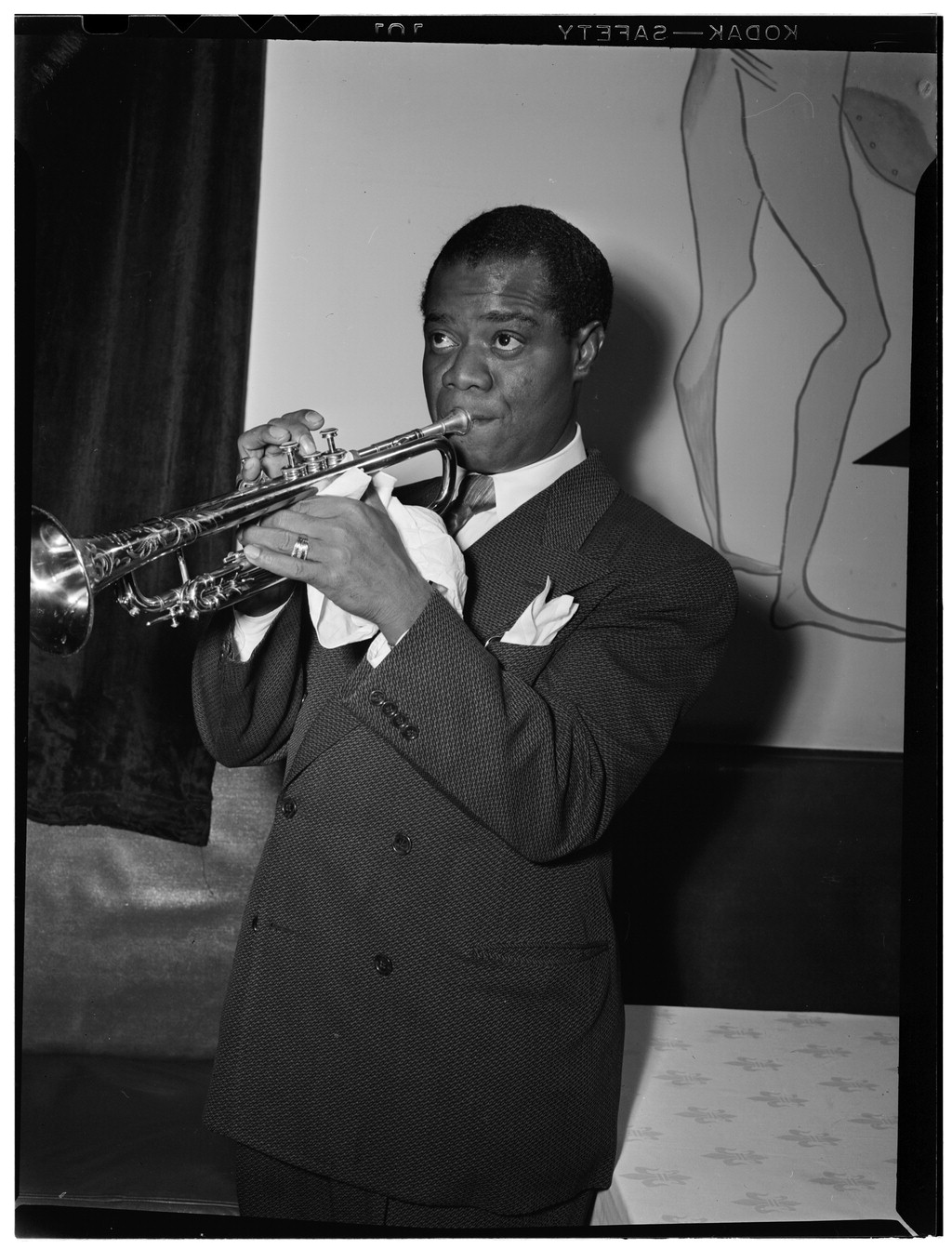

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.