Both communities of color and communities of artists have had to take care of each other in the U.S., creating systems of support where the dominant culture fosters neglect and deprivation. In the early twentieth century, at the nexus of these two often overlapping communities, we meet Langston Hughes and the artists, poets, and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes’ brilliantly compressed 1951 poem “Harlem” speaks of the simmering frustration among a weary people. But while its startling final line hints grimly at social unrest, it also looks back to the explosion of creativity in the storied New York City neighborhood during the Great Depression.

Hughes had grown reflective in the 50s, returning to the origins of jazz and blues and the history of Harlem in Montage of a Dream Deferred. The strained hopes and hardships he had eloquently documented in the 20s and 30s remained largely the same post-World War II, and one of the key features of Depression-era Harlem had returned; Rent parties, the wild shindigs held in private apartments to help their residents avoid eviction, were back in fashion, Hughes wrote in the Chicago Defender in 1957.

“Maybe it is inflation today and the high cost of living that is causing the return of the pay-at-the-door and buy-your-own-refreshments parties,” he said. He also noted that the new parties weren’t as much fun.

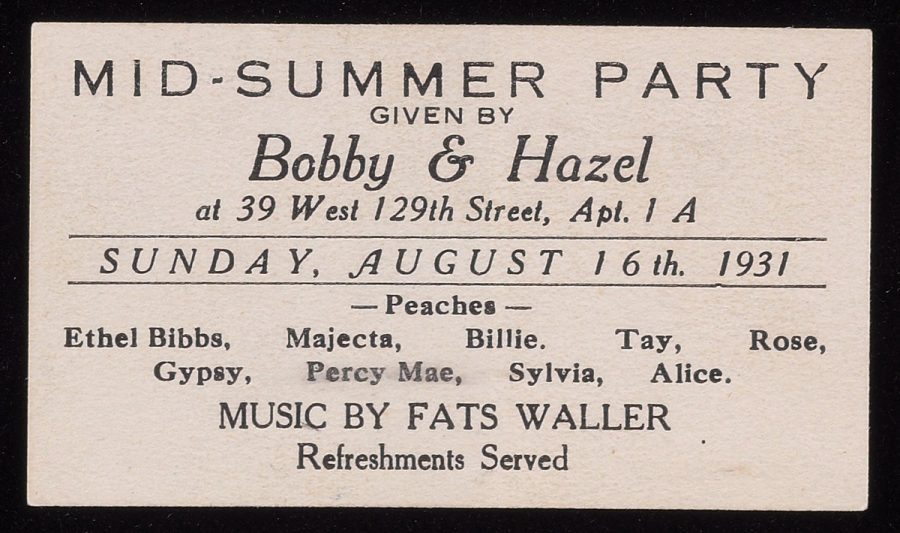

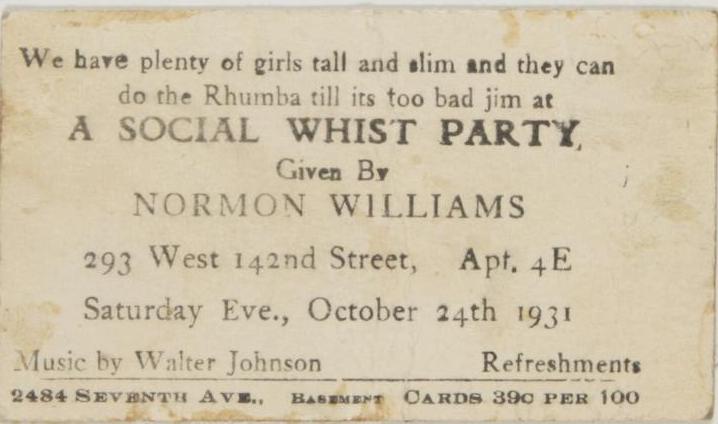

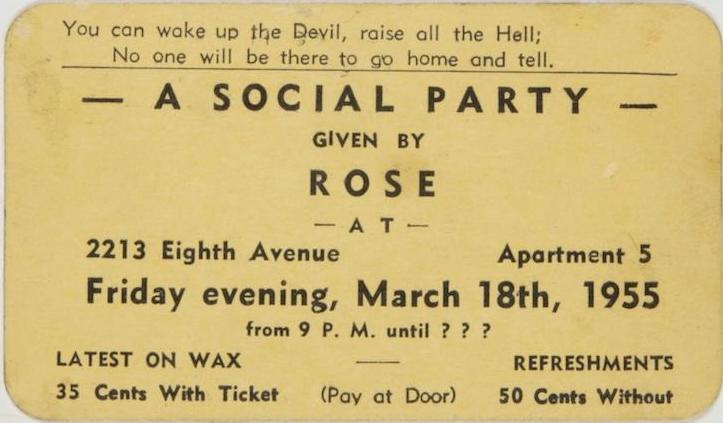

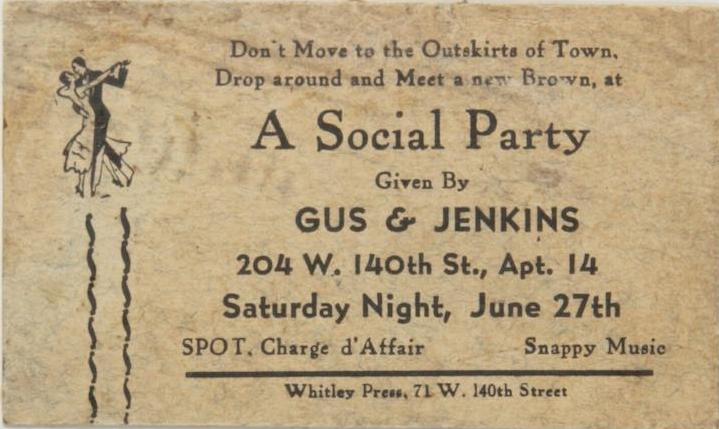

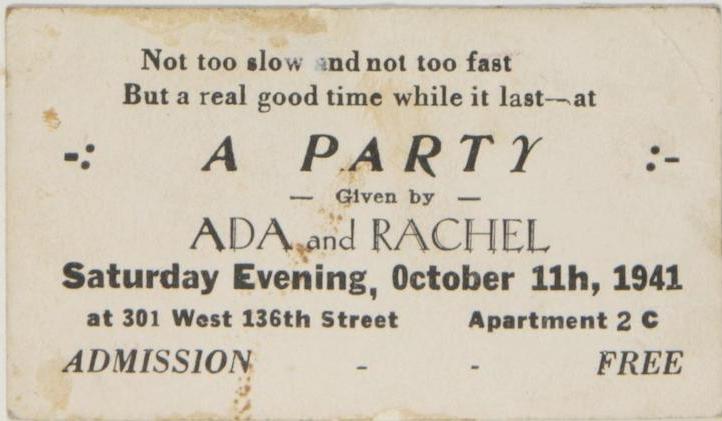

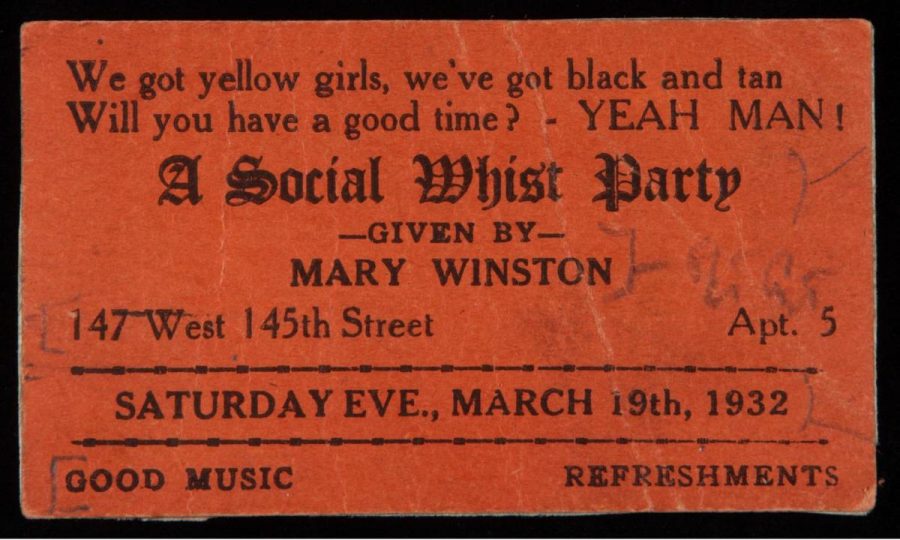

But how could they be? Depression-era rent parties were legendary. They “impacted the growth of Swing and Blues dancing,” writes dance teacher Jered Morin, “like few other periods.” As Hughes commented, “the Saturday night rent parties that I attended were often more amusing than any night club, in small apartments where God-knows-who lived.” Famous artists met and rubbed elbows, musicians formed impromptu jams and invented new styles, working class people who couldn’t afford a night out got to put on their best clothes and cut loose to the latest music. Hughes was fascinated, and as a writer, he was also quite taken by the quirky cards used to advertise the parties. “When I first came to Harlem,” he said, “as a poet I was intrigued by the little rhymes at the top of most House Rent Party cards, so I saved them. Now I have quite a collection.”

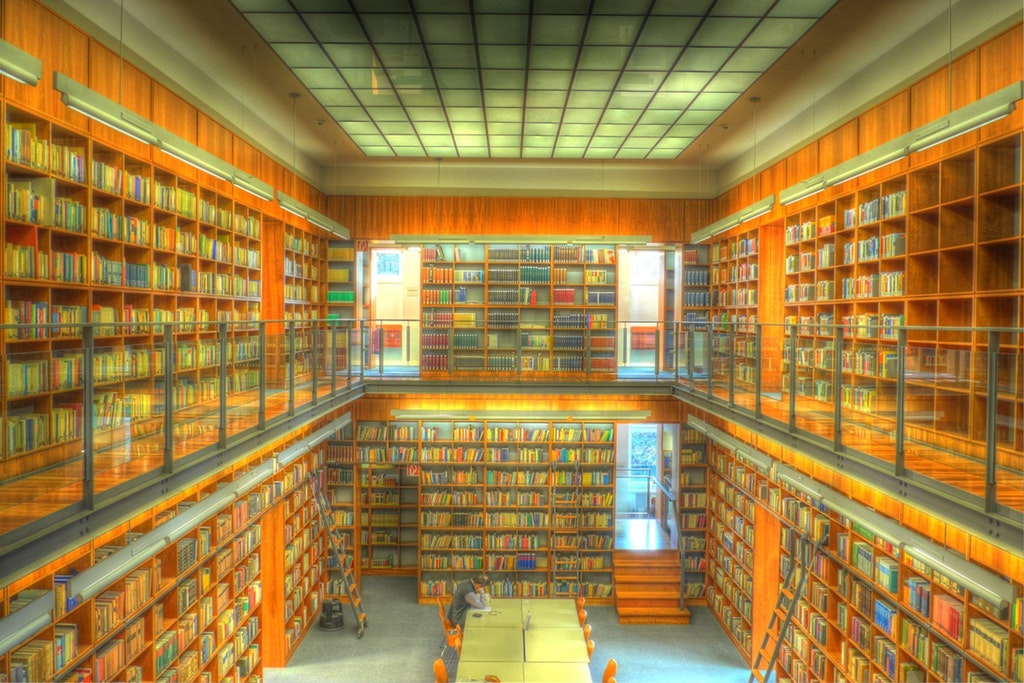

The cards you see here come from Hughes’ personal collection, held with his papers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Many of these date from the 40s and 50s, but they all draw their inspiration from the Harlem Renaissance period, when the phenomenon of jazz-infused rent parties exploded. “Sandra L. West points out that black tenants in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s faced discriminatory rental rates,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate. “That, along with the generally lower salaries for black workers, created a situation in which many people were short of rent money. These parties were originally meant to bridge that gap.” A 1938 Federal Writers Project account put it plainly: Harlem “was a typical slum and tenement area little different from many others in New York except for the fact that in Harlem rents were higher; always have been, in fact, since the great war-time migratory influx of colored labor.”

Tenants took it in stride, drawing on two longstanding community traditions to make ends meet: the church fundraiser and the Saturday night fish fry. But rent parties could be raucous affairs. Guests typically paid a few cents to enter, and extra for food cooked by the host. Apartments filled far beyond capacity, and alcohol—illegal from 1919 to 1933—flowed freely. Gambling and prostitution frequently made an appearance. And the competition could be fierce. The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance writes that in their heyday, “as many as twelve parties in a single block and five in an apartment building, simultaneously, were not uncommon.” Rent parties “essentially amounted to a kind of grassroots social welfare,” though the atmosphere could be “far more sordid than the average neighborhood block party.” Many upright citizens who disapproved of jazz, gambling, and booze turned up their noses and tried to ignore the parties.

In order to entice party-goers and distinguish themselves, writes Onion, “the cards name the kind of musical entertainment attendees could expect using lyrics from popular songs or made-up rhyming verse as slogans.” They also “used euphemisms to name the parties’ purpose,” calling them “Social Whist Party” or “Social Party,” while also slyly hinting at rowdier entertainments. The new rent parties may not have lived up to Hughes’ memories of jazz-age shindigs, perhaps because, in some cases, live musicians had been replaced by record players. But the new cards, he wrote “are just as amusing as the old ones.”

Related Content:

Langston Hughes Presents the History of Jazz in an Illustrated Children’s Book (1955)

Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness