LSD was first synthesized in 1938 by chemist Albert Hoffman in a Swiss laboratory but only attained infamy almost two decades later, when it became part of a series of government experiments. At the same time, a UC Irvine psychiatrist, Oscar Janiger (“Oz” to his friends), conducted his own studies under very different circumstances. “Unlike most researchers, Janiger wanted to create a ‘natural’ setting,” writes Brandy Doyle for MAPS (the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies). He reasoned that “there was nothing especially neutral about a laboratory or hospital room,” so he “rented a house outside of LA, in which his subjects could have a relatively non-directed experience in a supportive environment.”

Janiger wanted his subjects to make creative discoveries in a state of heightened consciousness. The study sought, he wrote, to “illuminate the phenomenological nature of the LSD experience,” to see whether the drug could effectively be turned into a creativity pill. He found, over a period lasting from 1954 to 1962 (when the experiments were terminated), that among his approximately 900 subjects, those who were in therapy “had a high rate of positive response,” but those not in therapy “found the experience much less pleasant.” Janiger’s findings have contributed to the research that organizations like MAPS have done on psychoactive drugs in therapeutic settings. The experiments also produced a body of artwork made by study participants on acid.

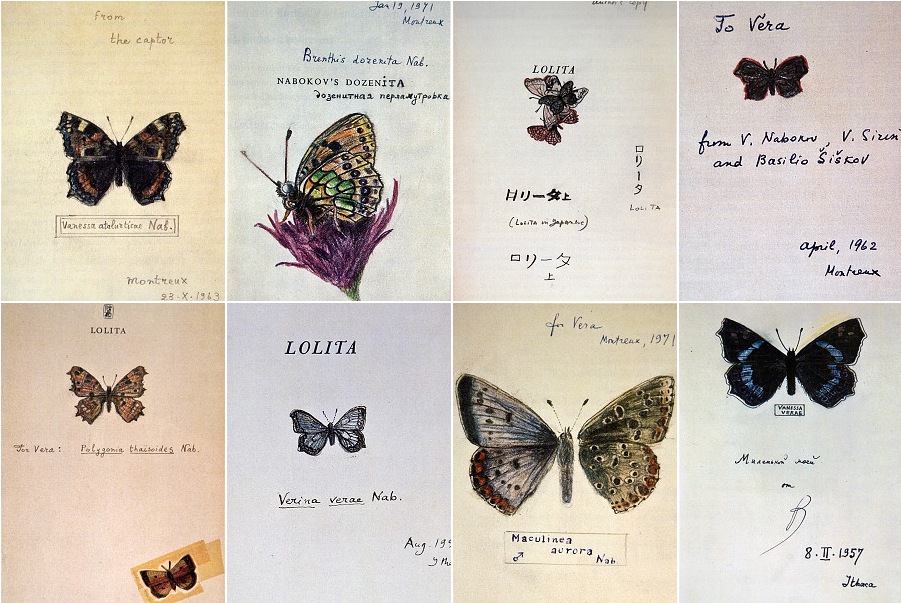

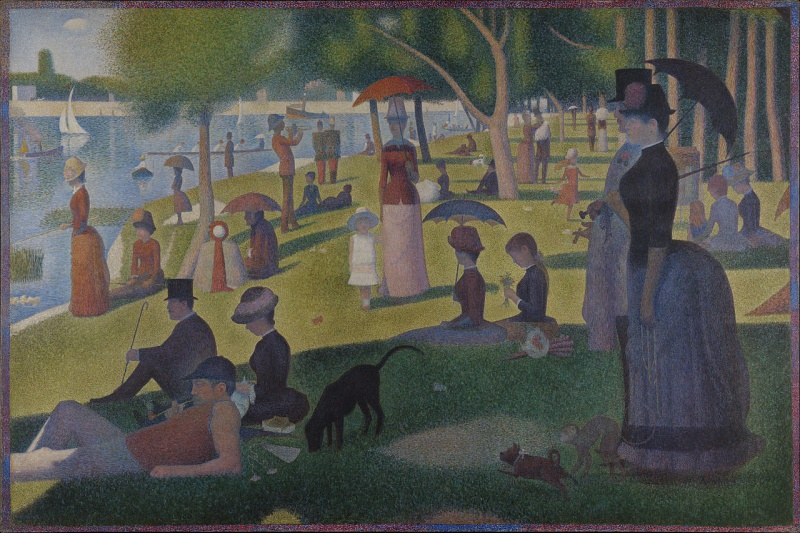

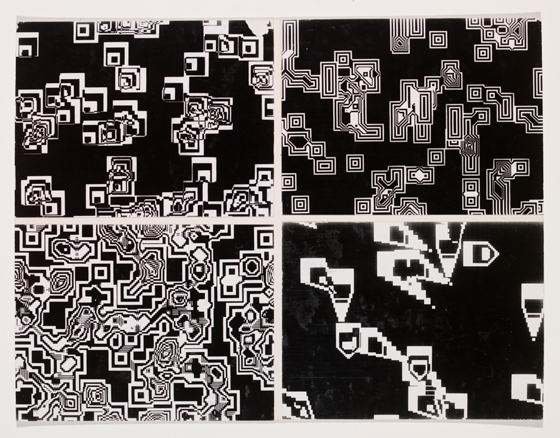

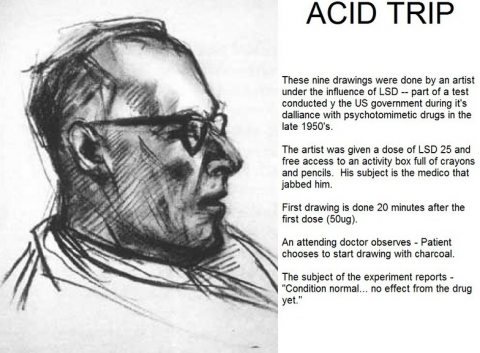

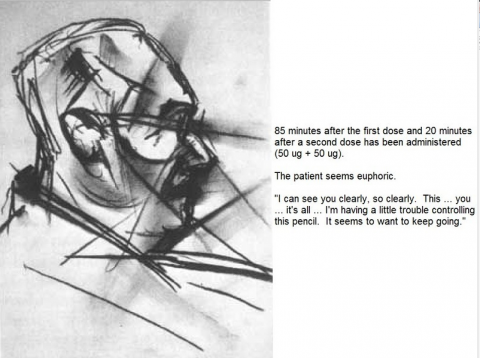

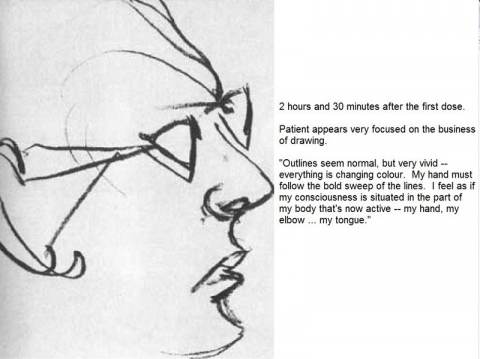

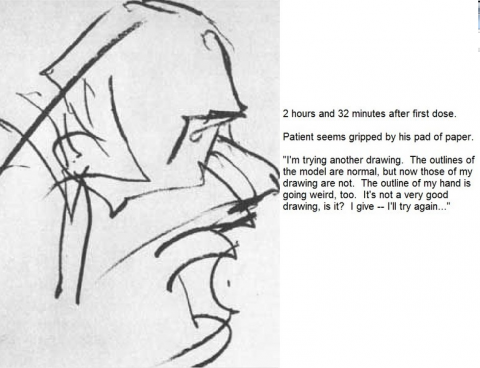

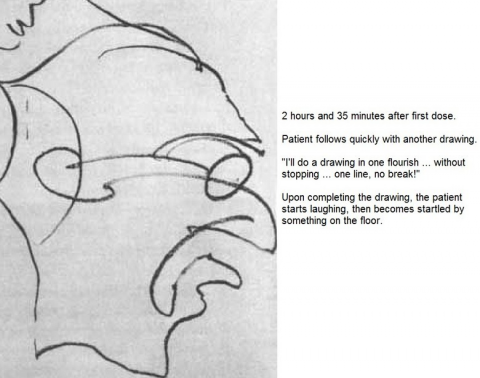

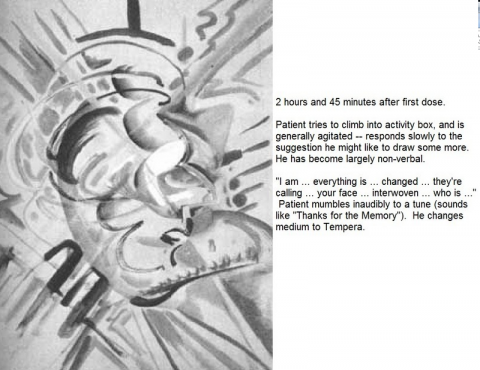

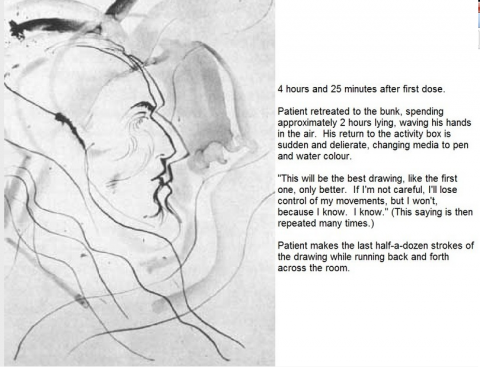

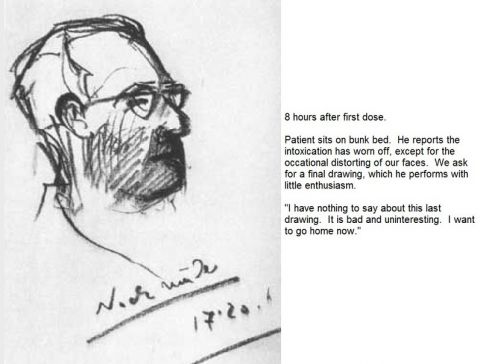

Janiger invited over 100 professional artists into the study and had them produce over 250 paintings and drawings. The series of eight drawings you see here most likely came from one of those artists (though “the records of the identity of the principle researcher have been lost,” writes LiveScience). In the psych-rock-scored video at the top see the progression of increasingly abstract drawings the artist made over the course of his 8‑hour trip. He reported on his perceptions and sensations throughout the experience, noting, at what seems to be the drug’s peak moment at 2.5 and 3 hours in, “I feel that my consciousness is situated in the part of my body that’s active—my hand, my elbow, my tongue…. I am… everything is… changed… they’re calling… your face… interwoven… who is….”

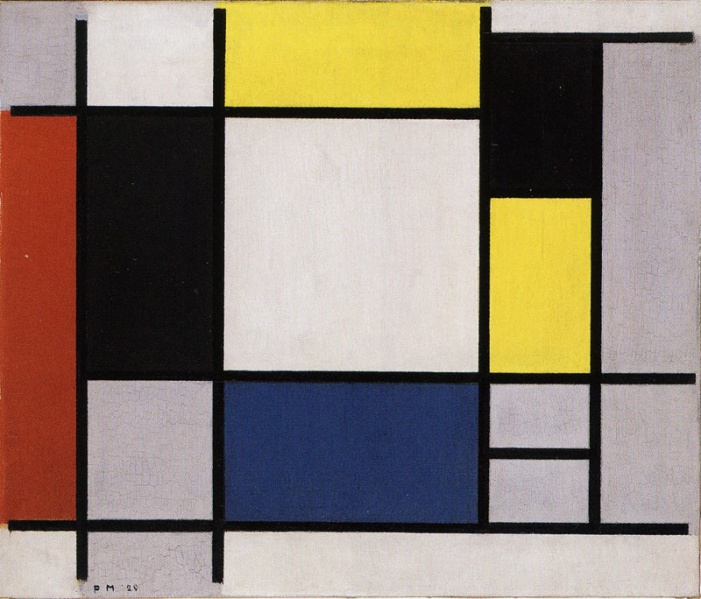

Trippy, but there’s much more to the experiment than its immediate effects on artists’ brains and sketches. As Janiger’s colleague Marlene Dobkin de Rios writes in her definitive book on his work, “all of the artists who participated in Janiger’s project said that LSD not only radically changed their style but also gave them new depths to understand the use of color, form, light, or the way these things are viewed in a frame of reference. Their art, they claimed, changed its essential character as a consequence of their experiences.” Psychologist Stanley Krippner made similar discoveries, and “defined the term psychedelic artist” to describe those who, as in Janiger’s studies “gained a far greater insight into the nature of art and the aesthetic idea,” Dobkin de Rios writes.

Artistic productions—paintings, poems, sketches, and writings that stemmed from the experience—often show a radical departure from the artist’s customary mode of expression… the artists’ general opinion was that their work became more expressionistic and demonstrated a vastly greater degree of freedom and originality.

The work of the unknown artist here takes on an almost mystical quality after a while. The project began “serendipitously” when one of Janiger’s volunteers in 1954 insisted on being able to draw during the dosing. “After his LSD experience,” writes Dobkin de Rios, “the artist was very emphatic that it would be most revealing to allow other artists to go through this process of perceptual change.” Janiger was convinced, as were many of his more famous test subjects.

Janiger reportedly introduced LSD to Cary Grant, Anais Nin, Jack Nicholson, and Aldous Huxley during guided therapy sessions. Still, he is not nearly as well-known as other LSD pioneers like Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary, in part because, writes the psychoactive research site Erowid, “his data remained largely unpublished during his lifetime,” and he was not himself an artist or media personality (though he was a cousin of Allen Ginsberg).

Janiger not only changed the consciousness of unnamed and famous artists with LSD, but also experimented with DMT with Alan Watts and fellow psychiatrist Humphry Osmond (who coined the word “psychedelic”), and conducted research on peyote with Dobkin de Rios. To a great degree, we have him to thank (or blame) for the explosion of psychedelic art and philosophy that flowed out of the early sixties and indelibly changed the culture. At LiveScience, you can see a slideshow of these drawings with commentary from Yale physician Andrew Sewell on what might be happening in the tripping artist’s brain.

Note: IAI Academy has just released a short course called The Science of Psychedelics. You can enroll in it here.

Related Content:

Hofmann’s Potion: 2002 Documentary Revisits History of LSD

Ken Kesey Talks About the Meaning of the Acid Tests

Aldous Huxley’s Most Beautiful, LSD-Assisted Death: A Letter from His Widow

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness