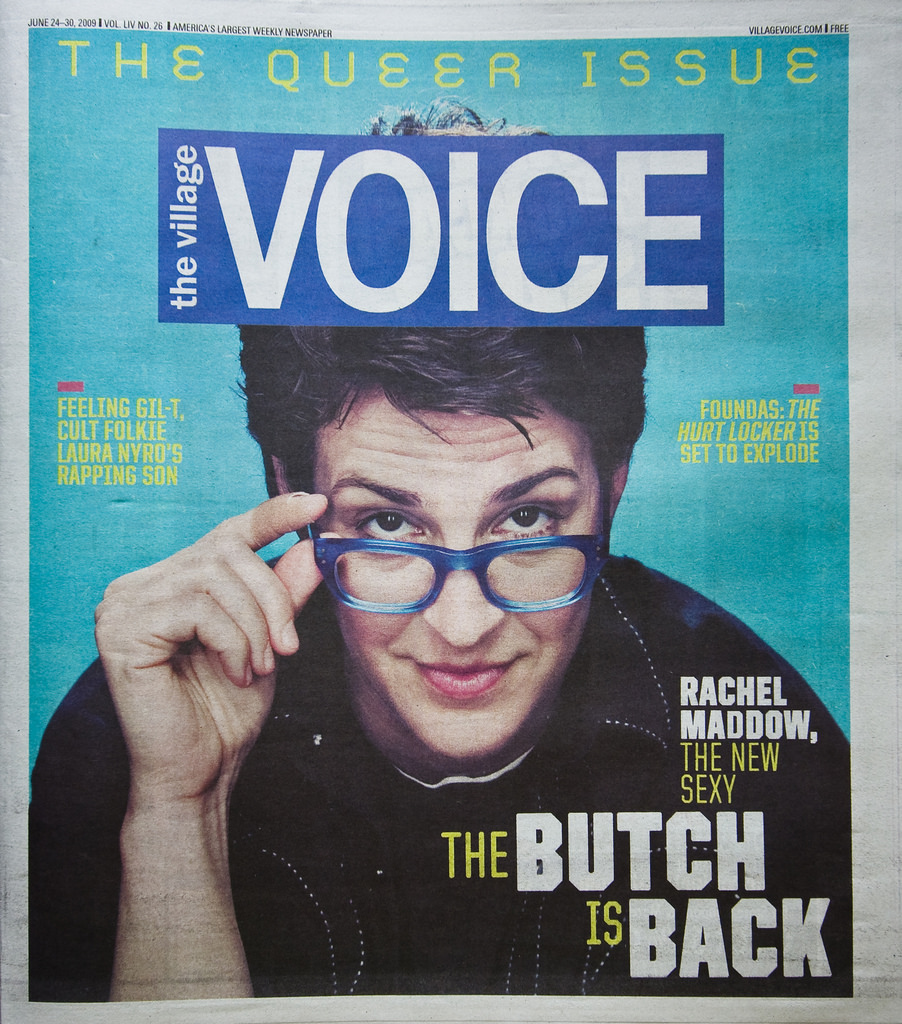

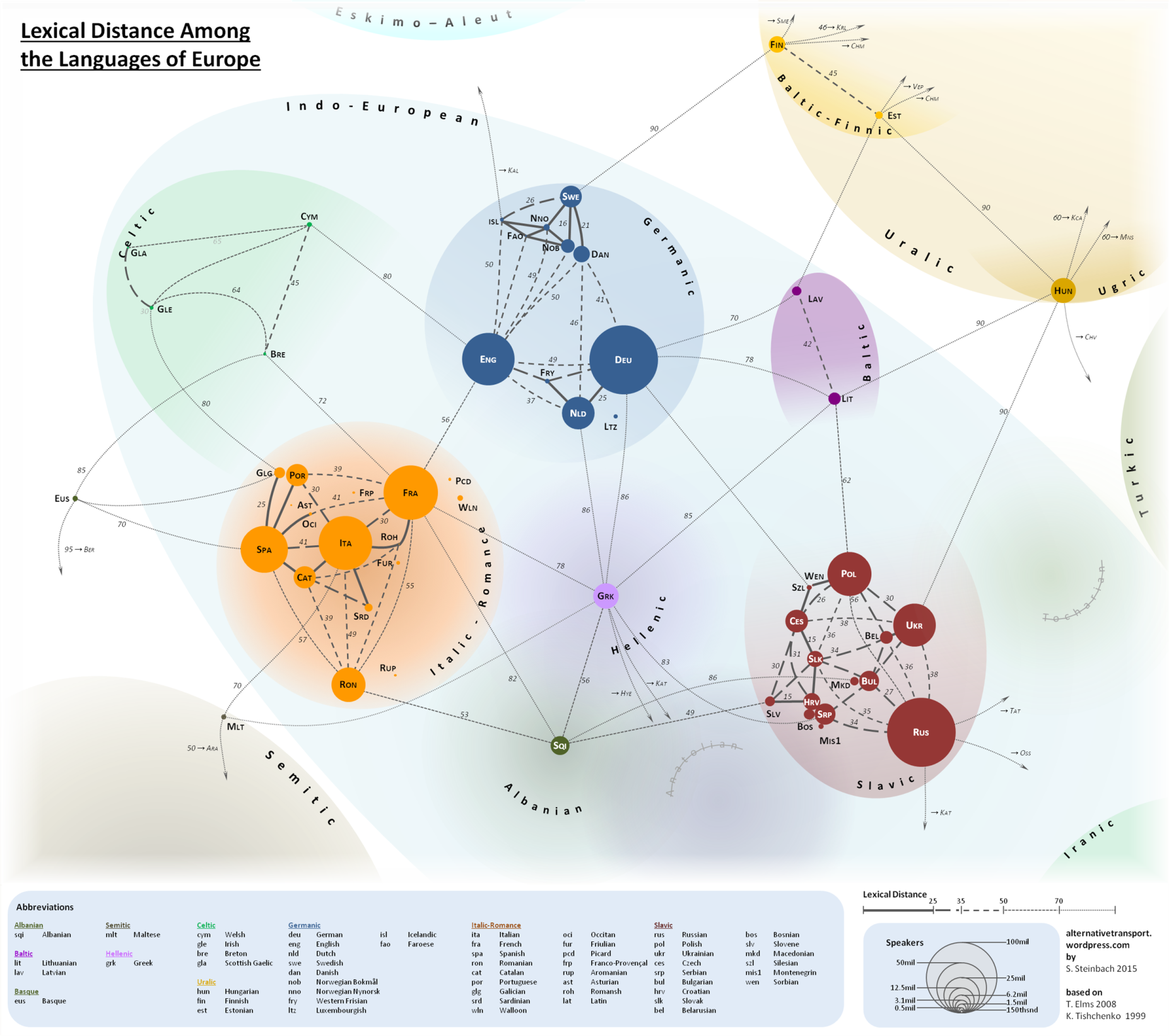

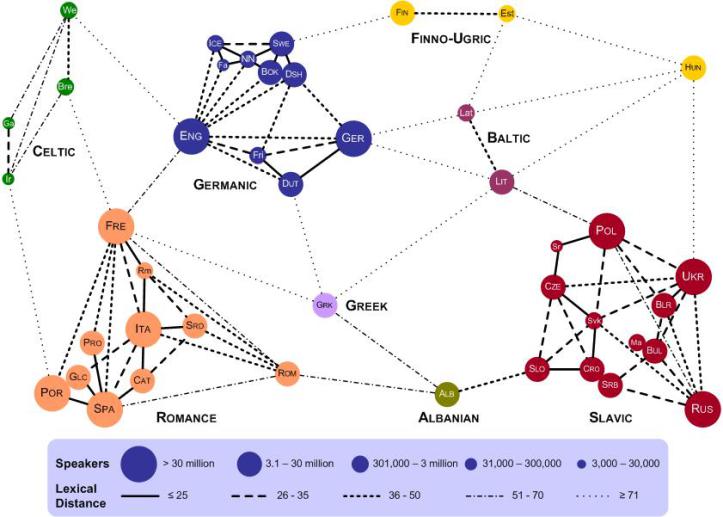

Stephen F. Steinbach, a resident of Vienna and a “cartography, language and travel enthusiast, with an engineering background,” is not a linguist. Steinbach, who runs the site Alternative Transport, seems much more interested in mapping and transportation than morphology and etymology. But he has made a contribution to a linguistic concept called “lexical difference” with the map you see above, a colorful 2015 visualization of European languages, grouped together in clusters according to their subfamilies (Italic-Romance, Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, etc.—see a much larger version here).

Straight and arcing lines span the relative distance these languages have presumably traveled from each other. Solid lines between languages represent a very close proximity, dashed lines of different thicknesses show more distance, and thin dotted lines traverse the greatest expanses.

Hungarian and Ukrainian, for example, have a lexical distance score of 90, where Polish and Ukrainian, both Slavic languages, are only 30 degrees from each other. “The map shows the language families that cover the continent,” writes Big Think, “large, familiar ones like Germanic, Italic-Romance and Slavic, smaller ones like Celtic, Baltic and Uralic; outliers like Semitic and Turkic; and isolates—orphan languages, without a family: Albanian and Greek.” (Technically, modern Greek does have a family—Hellenic—though it is the only surviving member.)

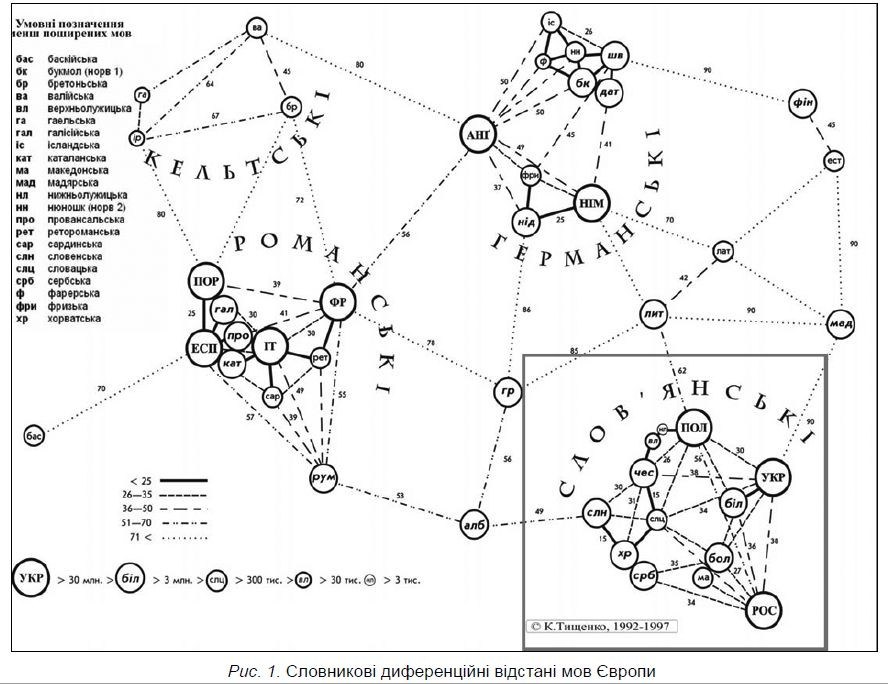

As we might expect from this subset of the durable Indo-European schema, the languages within each clustered group occupy the shortest distance from each other, with some exceptions. Romanian, for example, is slightly closer to Albanian than it is to French, its Romance cousin. The Slavic languages Russian and Polish seem to have traveled a bit further apart than Polish has from the Baltic language of Lithuanian. What does this mean, exactly? According to the measure of “lexical distance” proposed by Ukrainian linguist Konstantin Tishchenko, it means that closer languages might be more mutually intelligible, at least from a lexical standpoint, since they may share more cognates (similar-sounding and meaning words) and borrowings.

Gaston Ümlaut, the handle of a linguist on the Stack Exchange Linguistics beta, cautions that the concept of “lexical distance” may be “pretty useless” given that the comparisons also include false cognates—words that sound or look similar but have no relationship to each other. These could account for some seeming inconsistencies. (Ümlaut admits he has not read the original article, written in Russian. If you are able, you can find it online in the book Metatheory of Linguistics, here.) Steinbach has responded in the same thread.

The idea received a much more trenchant critique more recently. Steinbach clarified that the theory, and the map, only compare written words and not syntax or speech. “It has nothing to do with grammar, syntax, rhythm or other important features that are important for intelligibility,” he writes. “It also compares a small list of words and not the entire vocabulary of one language to another.” This explanation does cast doubt on whether “lexical distance” is a meaningful concept. I’ll leave it to the linguists to decide. (Steinbach reached out to Tischchenko but has yet to receive a reply.)

Tischchenko’s original “lexical distance” map, further up, drawn in 1997, gets the idea across with minimal fuss, but it leaves much to be desired graphically. (A large, hand-drawn color version improves upon the printed map.) Steinbach took his version from a 2008 English-language adaptation made by Teresa Elms in 2008 (above). In his blog post here, he explains all of the changes he made to Elms and Tischchenko’s designs. These include adjusting the size of the “bubbles” to proportionally represent the number of speakers of each language. Steinbach also added several languages, as well as “gravestones” for the dead Anatolian and Tocharian branches. In all, his map shows “54 languages, representing 670 million people.” He adds, vaguely, that “it checks out.”

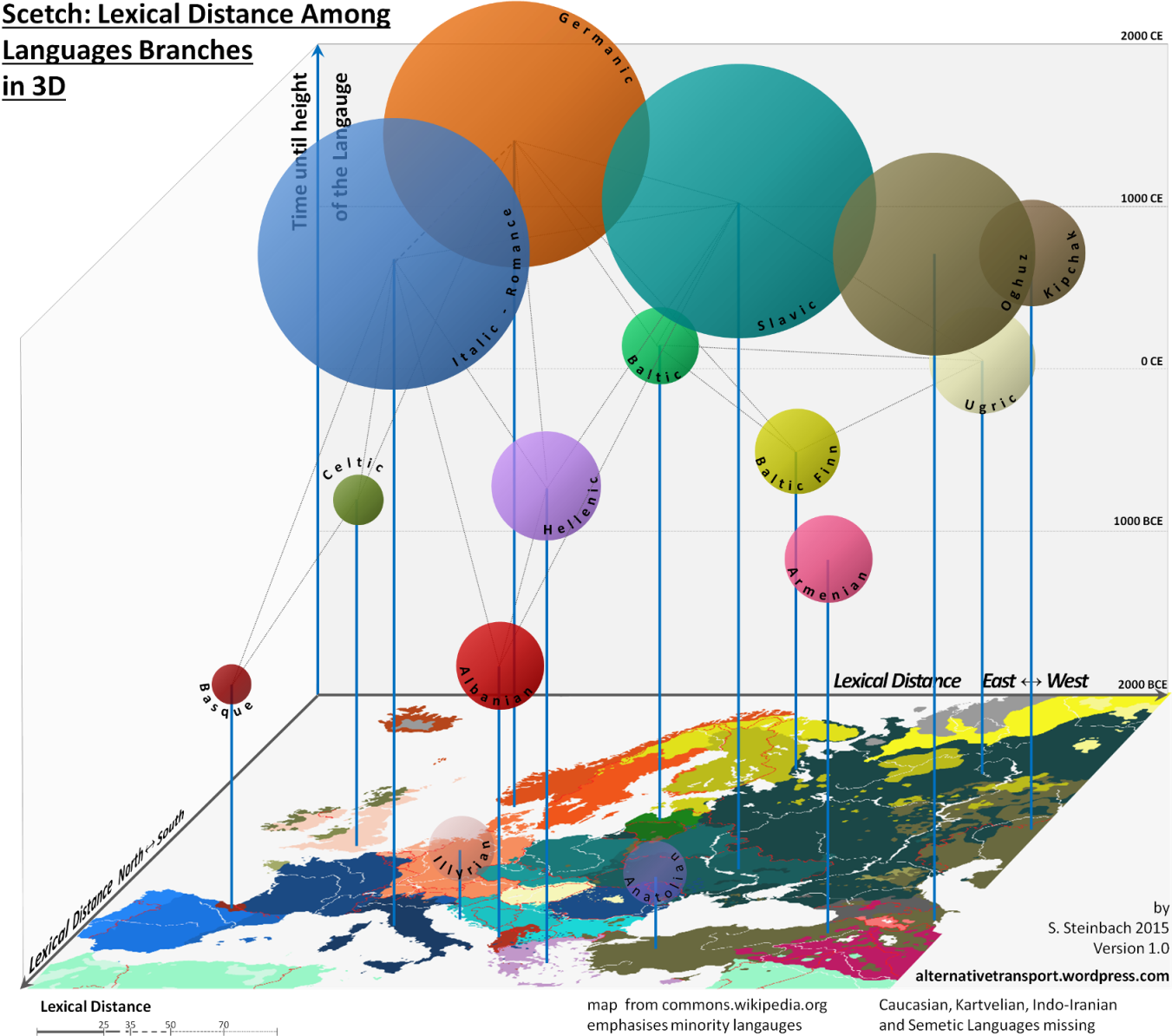

After posting his Lexical Distance Map, Steinbach proposed a “3D” version, with the added dimension of time. (See his preliminary sketch above.) The maps are intriguing, the theory of “lexical distance” an interesting one, but we should bear in mind, as Steinbach writes, that he is “no linguist,” and that this idea is hardly an orthodox one within the discipline.

via Big Think

Related Content:

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

How Languages Evolve: Explained in a Winning TED-Ed Animation

Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness