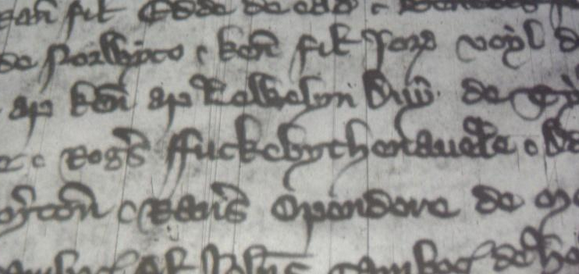

Photo by Paul Booth

You value decorum, propriety, eloquence, you treasure le mot juste and agonize over diction as you compose polite but strongly-worded letters to the editor. But alas, my literate friend, you have the misfortune of living in the age of Twitter, Tumblr, et al., where the favored means of communication consists of readymade mimetic words and phrases, photos, videos, and animated gifs. World leaders trade insults like 5th graders—some of them do not know how to spell. Respected scientists and journalists debate anonymous strangers with cartoon avatars and work-unsafe pseudonyms. Some of them are robots.

What to do?

Embrace it. Insert well-placed profanities into your communiqués. Indulge in bawdiness and ribaldry. You may notice that you are doing no more than writers have done for centuries, from Rabelais to Shakespeare to Voltaire. Profanity has evolved right alongside, not apart from, literary history. T.S. Eliot, for example, knew how to go lowbrow with the best of them, and gets credit for the first recorded use of the word “bullshit.” As for another, even more frequently used epithet in 24-hour online commentary?—well, the word “F*ck” has a far longer history, granting its apt public use recently by seismologist Steven Gibbons an added authority.

Not long ago we alerted you to the first known use of the versatile obscenity in a 1528 marginal note scribbled in Cicero’s De Officiis by a monk cursing his abbot. Not long after this discovery, notes Medievalists.net, another scholar found the word in a 1475 poem called Flen flyys. This was thought to be the earliest appearance of “f*ck” as a purely sexual reference until medieval historian Paul Booth of Keele University discovered an instance dating over a hundred years earlier. Rather than within, or next to, a work of literature, however, the word appears in a set of 1310 English court records. And no, it is decidedly not a legal term.

The documents concern the case of “a man named Roger Fuckebythenavele.” Used three times in the record, the name, says Booth, is probably not a joke made by the scribe but some kind of bizarre nickname, though one hopes not a description of the crime. “Either it refers to an inexperienced copulator, referring to someone trying to have sex with a navel,” says Booth, stating the obvious, “or it’s a rather extravagant explanation for a dimwit, someone so stupid they think that this is the way to have sex.” Our medieval gent had other problems as well. He was called to court three times within a year before being pronounced “outlawed,” which The Independent’s Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith suggests execution but probably refers to banishment.

For the word to have such casually hilarious or insulting currency in the early 14th century, it must have come from an even earlier time. Indeed, “f*ck is a word of German origin,” notes Jesse Sheidlower, author of an etymological history called The F Word, “related to words in several other Germanic languages, such as Dutch, German, and Swedish, that have sexual meanings as well as meaning such as ‘to strike’ or ‘to move back and forth’” (naturally). So, in other words, it’s just a word. But in this case it might have also been a weapon, Booth speculates, wielded “by a revengeful former girlfriend. Fourteenth-century revenge porn perhaps…” If that’s not evidence for you that the present may not be unlike the past, then maybe take note of the appearance of the word “twerk” in 1820.

Related Content:

Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW)

Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness