Surely we’ve all wondered what we might do as prominent nineteenth-century industrialists, and more than a few of us (especially here in the Open Culture crowd) would no doubt invest our fortunes in the art of the world. Railcar manufacturing magnate Charles Lang Freer did just that, as we can see today in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Together with the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Sackler having made it as “the father of modern pharmaceutical advertising”), it constitutes the Smithsonian Institution’s national museum of Asian art, gathering everything from ancient Egyptian stone sculpture to Chinese paintings to Korean pottery to Japanese books.

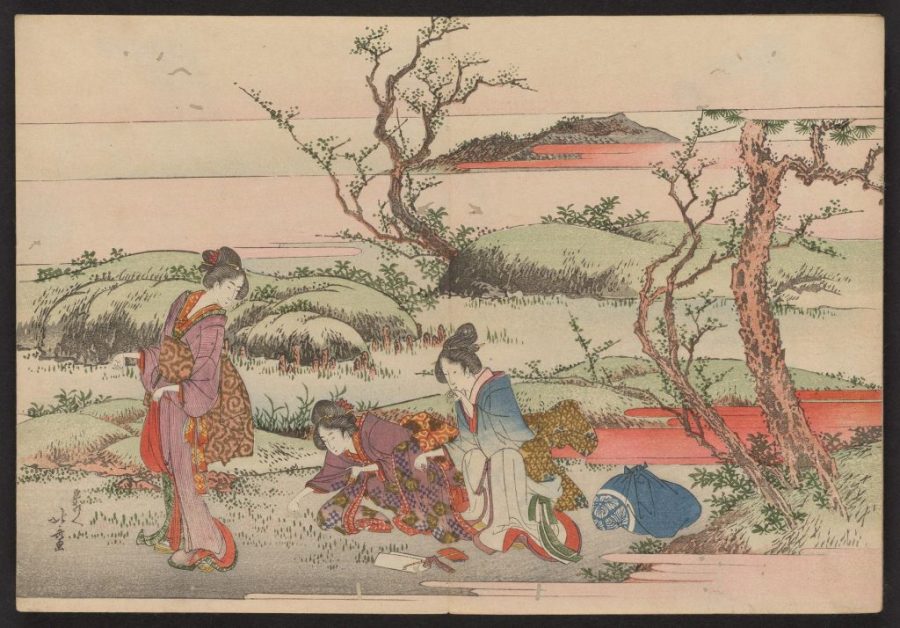

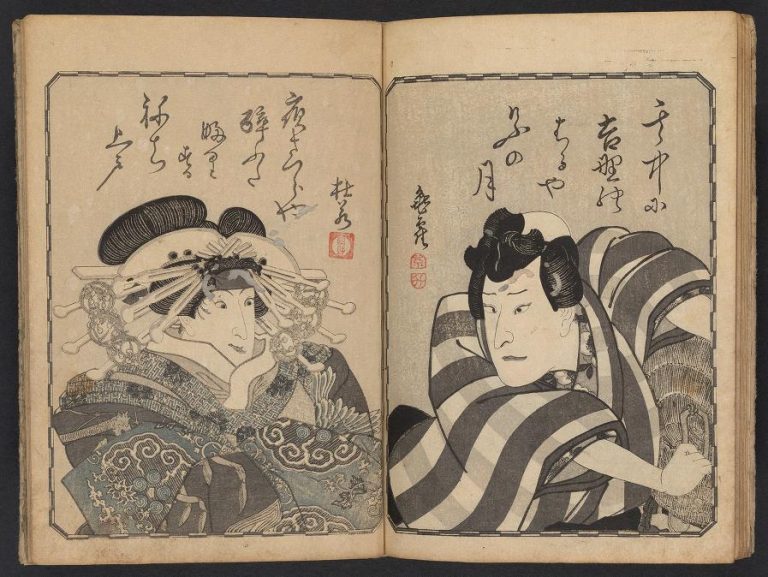

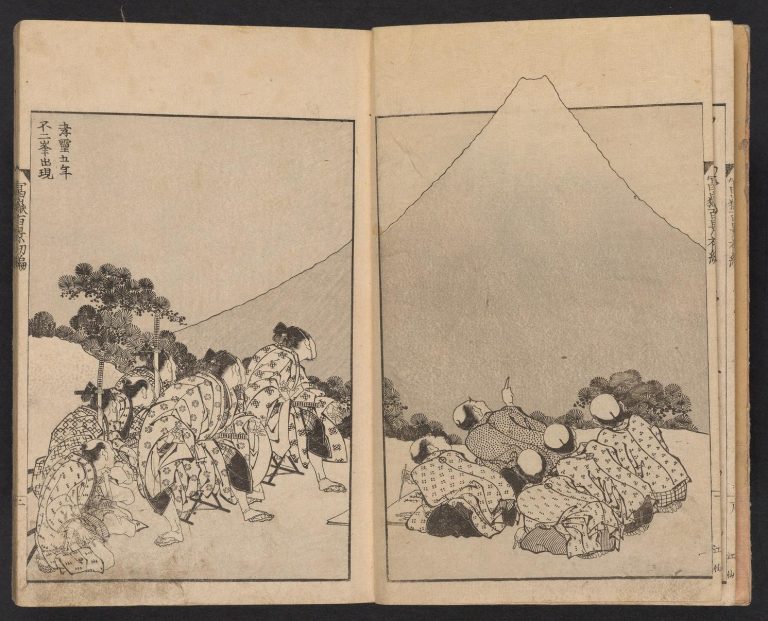

We like to highlight Japanese book culture here every so often (see the related content below) not just because of its striking aesthetics and consummate craftsmanship but because of its deep history. You can now experience a considerable swath of that history free online at the Freer|Sacker Library’s web site, which just this past summer finished digitizing over one thousand books — now more than 1,100, which breaks down to 41,500 separate images — published during Japan’s Edo and Meiji periods, a span of time reaching from 1600 to 1912. “Often filled with beautiful multi-color illustrations,” writes Reiko Yoshimura at the Smithsonian Libraries’ blog, “many titles are by prominent Japanese traditional and ukiyo‑e (‘floating world’) painters such as Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716), Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849).”

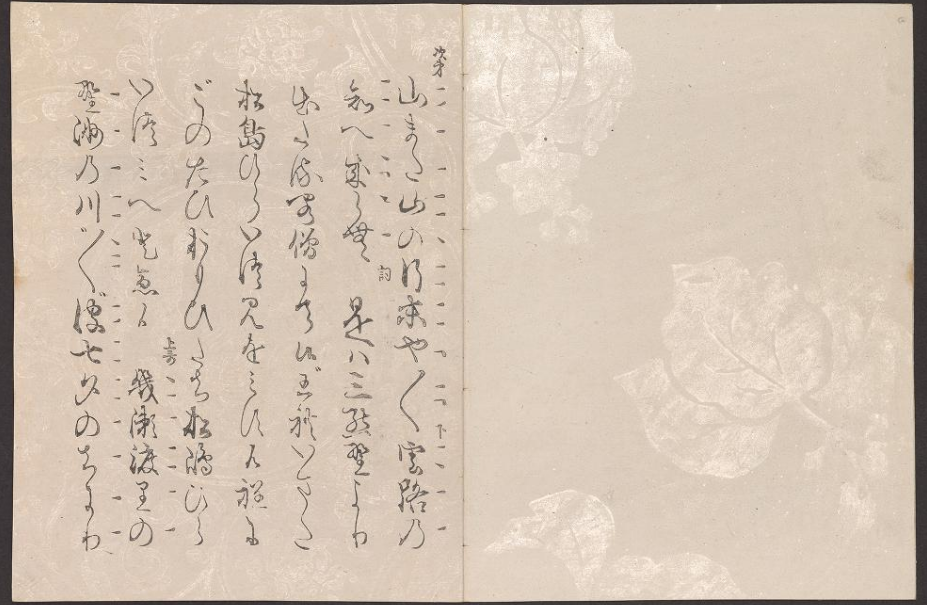

Yoshimura directs readers to such volumes as Hokusai’s One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Utagawa Toyokuni’s Thirty-Six Popular Actors, and artist, craftsman, and designer Kōetsu’s collection of one hundred librettos for noh theater performances. Even those who can’t read classical Japanese will admire an aesthete like Kōetsu’s way with what Yoshimura calls his “caligraphic ‘font,’ ” all “skillfully printed on luxurious mica embellished papers using wooden movable-type.”

While the online collection’s scans come in a more than high enough resolution for general appreciation, to get the full effect of bookmaking techniques like mica embellishment — which only sparkles when seen in real life — you’d have to visit the physical collection. Some things, it seems, can’t yet be digitized.

Enter the collection of Japanese Illustrated Books here.

Related Content:

Watch a Japanese Craftsman Lovingly Bring a Tattered Old Book Back to Near Mint Condition

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.