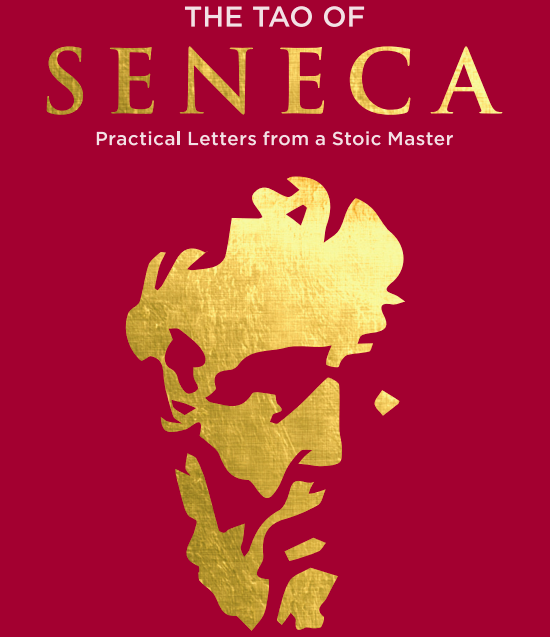

“The greatest obstacle to living is expectancy, which hangs upon tomorrow and loses today,” wrote Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger. “You are arranging what is in Fortune’s control and abandoning what lies in yours.” That still much-quoted observation from the first-century Roman philosopher and statesman, best known simply as Seneca, has a place in a much larger body of work. Seneca’s writings stand, along with those of Zeno, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, as a pillar of Stoic philosophy, a system of thinking which emphasizes the primacy of personal virtue and the importance of observing oneself objectively and mastering, instead of being mastered by, one’s own emotions.

The Stoics found their way of life beneficial indeed in the harsh reality of more than 2,000 years ago, but Stoicism loses none of its value when practiced by those of us living today.

“At its core, it teaches you how to separate what you can control from what you cannot, and it trains you to focus exclusively on the former,” writes self-improvement maven Tim Ferriss in his introduction to The Tao of Seneca, the three-volume collection of Seneca’s letters, illustration and lined modern commentary, that he’s just published free on the internet. (For instructions on how to upload them to your Kindle, see this page.)

Of all the Stoics, he continues, “Seneca stands out as easy to read, memorable, and surprisingly practical. He covers specifics ranging from handling slander and backstabbing, to fasting, exercise, wealth, and death.” (Ferriss has also created audiobook versions of the texts, which you can buy through Audible. Or get a couple for free by signing up for Audible’s 30-day free trial program.)

Ferris suggests making Seneca “part of your daily routine. Set aside 10–15 minutes a day and read one letter. Whether over coffee in the morning, right before bed, or somewhere in between, digest one letter.” He also adds that “Stoicism has spread like wildfire throughout Silicon Valley and the NFL in the last five years, becoming a mental toughness training system for CEOs, founders, coaches, and players alike,” evidencing a results-oriented approach that may divide Stoicism enthusiasts, many of whom believe that the true Stoic should never consider the product, which will always lie outside one’s realm of control, but only the process. But even the ancients would surely agree that any prompt to action is worth taking, especially when it asks the cost of not a single coin — drachma, denarius, penny, or bit.

The Tao of Seneca will be added to our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices.

(via /r/stoicism)

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.