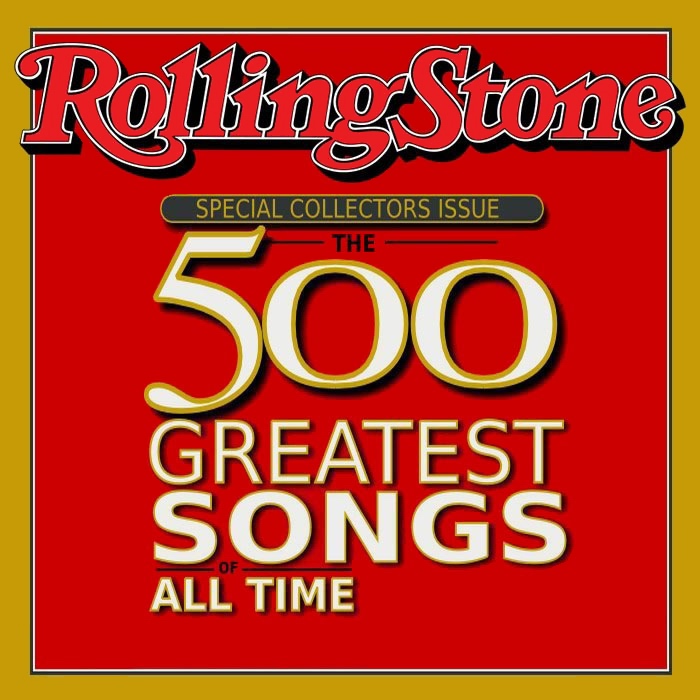

Whatever value one places in “best of” or “greatest” lists, it’s hard to deny they can be virtuoso exercises in critical concision. When running through 10, 50, 100 films, albums, novels etc. one can’t wander through the wildflowers but must make sparkly, punchy statements and move on. Rolling Stone’s writers have excelled at this form, and expanded the list size to 500, first releasing a book compiling their “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” in 2003 then following up the next year with the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” a special issue of the magazine with short blurbs about each selection.

In 2010, the magazine updated their massive list, compiled by 162 critics, for a special digital issue, and it now lives on their site with paragraph-length blurbs intact. Each one offers a fun little nugget of fact or opinion about the chosen songs. (Tom Petty, learning that The Strokes admitted to stealing his opening riff for “American Girl,” told the magazine, “I was like, ‘Ok, good for you.’ It doesn’t bother me.”) There’s hardly room to explain the rankings or justify inclusion. We’re asked to take the Rolling Stone writers’ collective word for it.

Maybe it’s a little difficult to argue with a list this big, since it includes a bit of everything—for the possible dross, there’s a whole lot of gold. The updated list swapped in 25 new songs and added an introduction by Jay‑Z: “A great song has all the key elements—melody; emotion; a strong statement that becomes part of the lexicon; and great production.” Broad enough criteria for great, but “greatest”? Put on the Spotify playlist above (or access it here) and judge for yourself whether most of those 500 songs in the updated list—472 to be exact—meet the bar.

You can see the original, 2004 list, sans blurbs, at the Internet Archive. Number one, Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (get it?). Number 500, Boston’s “More Than a Feeling,” which, well… okay. The updated list gives us Smokey Robinson’s “Shop Around” in last place (don’t worry, Smokey fans, “The Tracks of My Tears” makes it to 50.) Still at number one, naturally, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Find out which 498 songs sit in-between at the online list here. (Wikipedia has a percentage breakdown for both lists of songs by decade.) The magazine may be up for sale, its journalistic credibility in question, but for comprehensive “best of” lists that keep track of the movement of popular culture, we shouldn’t count them out just yet.

Related Content:

89 Essential Songs from The Summer of Love: A 50th Anniversary Playlist

The History of Punk Rock in 200 Tracks: An 11-Hour Playlist Takes You From 1965 to 2016

A Massive 800-Track Playlist of 90s Indie & Alternative Music, in Chronological Order

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness