There have been many times in American history when celebrations of the country’s multi-ethnic, ever-changing demography served as powerful counterweights to narrow, exclusionary, nationalisms. In 1855, for example, the publication of Brooklyn native Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself offered a “passionate embrace of equality,” writes Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, “the soul of democracy.” We can contrast the vibrancy and dynamism of Whitman’s vision with the violent nativism of the anti-immigrant Know-Nothings, who reached their peak in 1850. The movement was founded by two other New Yorkers, gang leader William “Bill the Butcher” Poole and writer Thomas R. Whitney, who asked in one of his political tracts, “What is equality but stagnation?”

Almost 100 years later, we see another nationalist movement taking hold, not only in Europe, but in the States. Before the U.S. entered World War II, its views on National Socialist Germany were decidedly ambivalent, with glowing portraits of its leader published throughout the 30s, and a sizable Nazi presence in the U.S. From 1934 to 1939, for example, German groups in the U.S. organized massive rallies in Madison Square Garden (see the first mass meeting of the “Friends of New Germany” above). Additionally, the German-American Bund promoted the Nazi Party throughout the U.S. with 70 different local chapters. These organizations held Nazi family and summer camps in New Jersey, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania…. “There were forced marches in the middle of the night to bonfires,” says historian Arnie Bernstein, “where the kids would sing the Nazi national anthem and shout ‘Sieg Heil.’”

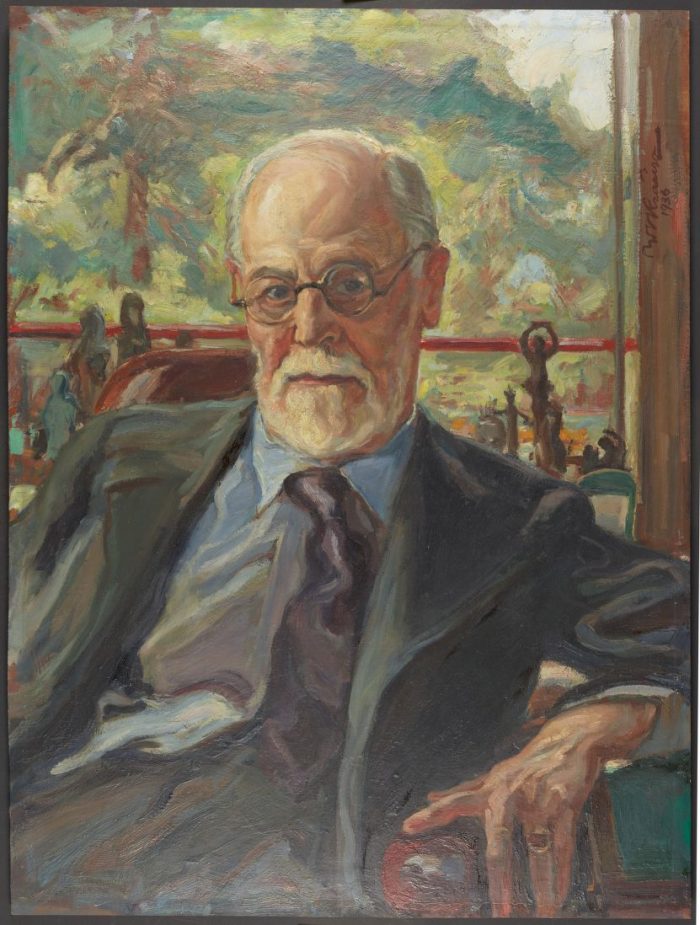

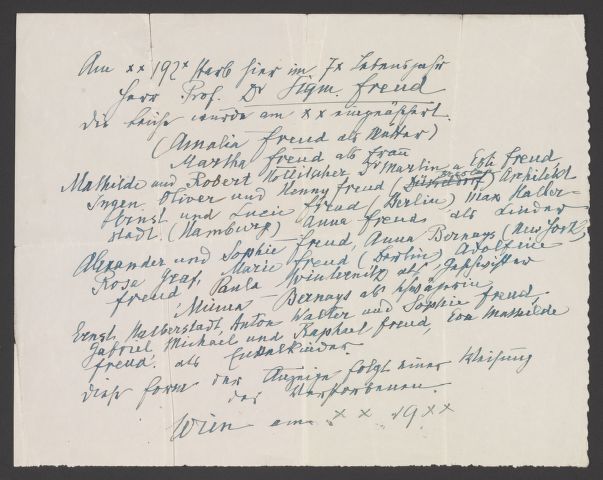

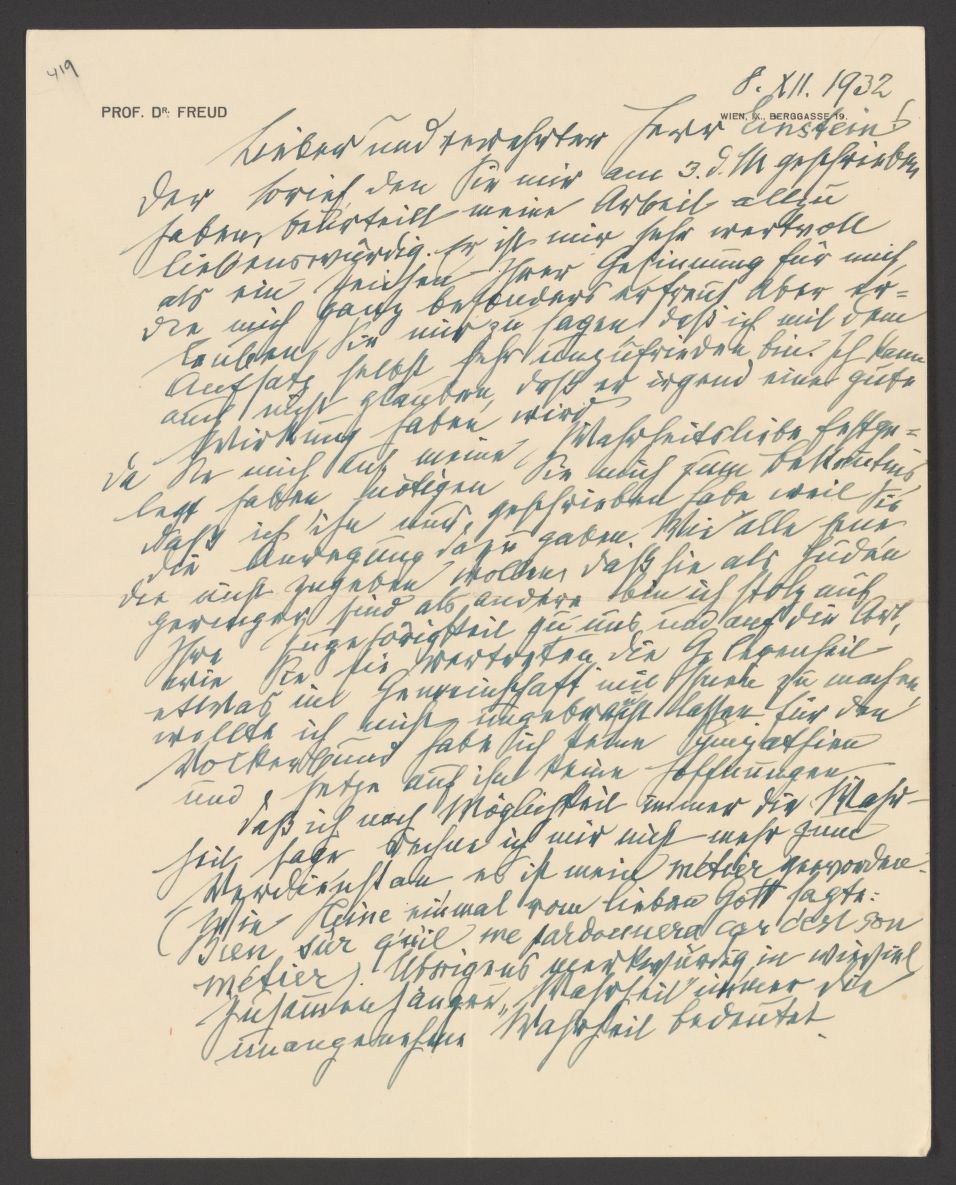

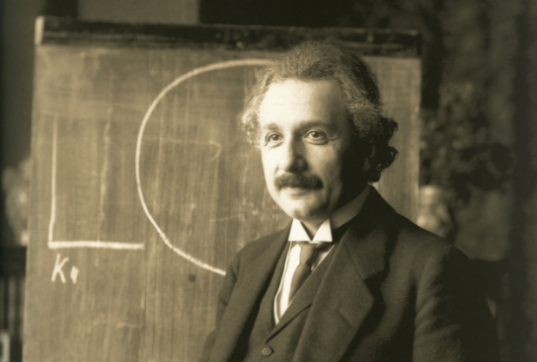

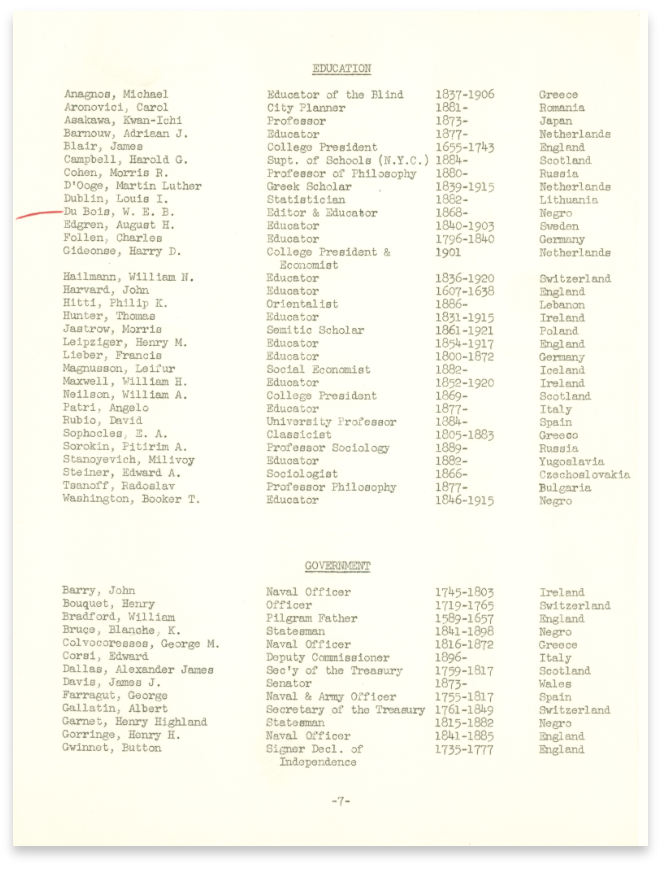

Needless to say, these scenes made a number of minority groups and immigrants particularly nervous, especially Jews who had just escaped from Europe. One such immigrant, physicist Albert Einstein, had made the U.S. his permanent home in 1933 when he accepted a position at Princeton after living as a refugee in England. He would go on to become a forceful advocate for equality in the U.S., speaking out against the racial caste system of segregation. In 1940, Einstein gave a little-known speech at the New York World’s Fair to inaugurate an exhibit that paid “homage to the diversity of the U.S. population.” On the display, called the “Wall of Fame,” were inscribed “the names and professions of hundreds of the nation’s most notable ‘immigrants, Negroes and American Indians.’” (See the first page of the typed list above, and the full list here.)

Einstein’s speech comes to us via Speeches of Note, a new sibling of two favorite sites of ours, Letters of Note and Lists of Note. Below, you can read the full transcript of the speech, in which Einstein—having adopted the country as it had adopted him—-declaims, “these, too, belong to us, and we are glad and grateful to acknowledge the debt that the community owes them.”

It is a fine and high-minded idea, also in the best sense a proud one, to erect at the World’s Fair a wall of fame to immigrants and Negroes of distinction.

The significance of the gesture is this: it says: These, too, belong to us, and we are glad and grateful to acknowledge the debt that the community owes them. And focusing on these particular contributors, Negroes and immigrants, shows that the community feels a special need to show regard and affection for those who are often regarded as step-children of the nation—for why else this combination?

If, then, I am to speak on the occasion, it can only be to say something on behalf of these step-children. As for the immigrants, they are the only ones to whom it can be accounted a merit to be Americans. For they have had to take trouble for their citizenship, whereas it has cost the majority nothing at all to be born in the land of civic freedom.

As for the Negroes, the country has still a heavy debt to discharge for all the troubles and disabilities it has laid on the Negro’s shoulders, for all that his fellow-citizens have done and to some extent still are doing to him. To the Negro and his wonderful songs and choirs, we are indebted for the finest contribution in the realm of art which America has so far given to the world. And this great gift we owe, not to those whose names are engraved on this “Wall of Fame,” but to the children of the people, blossoming namelessly as the lilies of the field.

In a way, the same is true of the immigrants. They have contributed in their way to the flowering of the community, and their individual striving and suffering have remained unknown.

One more thing I would say with regard to immigration generally: There exists on the subject a fatal miscomprehension. Unemployment is not decreased by restricting immigration. For unemployment depends on faulty distribution of work among those capable of work. Immigration increases consumption as much as it does demand on labor. Immigration strengthens not only the internal economy of a sparsely populated country, but also its defensive power.

The Wall of Fame arose out of a high-minded ideal; it is calculated to stimulate just and magnanimous thoughts and feelings. May it work to that effect.

The speech is remarkable for its egalitarianism. The exhibit works more or less as a “who’s who” of notable personalities—all of them men. Of course, Einstein himself was one of the most notable immigrants of the age. And yet, his ethos is Whitmanian, celebrating the multitudes of laborers and artists “blossoming namelessly” and those who have “remained unknown.” The country, Einstein suggests, could not possibly be itself without its diversity of people and cultures. That same year, Einstein would pass his citizenship test, and explain in a radio broadcast, “Why I am an American.”

Related Content:

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness