I left much of my reading of C.S. Lewis behind, but one quote of his will stay with me for life: “It is a good rule,” he advised, “after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.” I believe his advice is invaluable for maintaining a balanced perspective and achieving a healthy critical distance from the tumult of the present.

Reading works of ancient writers shows us how alike the mores and the crises of the ancients were to ours, and how vastly different. Those similarities and differences can help us evaluate certain current orthodoxies with greater wisdom. And that’s not to mention countless historians, novelists, poets, playwrights, critics, and philosophers from the past few hundred years, or several decades, who have much to teach us about where our modern ideas came from and how much they’ve deviated from their precedents.

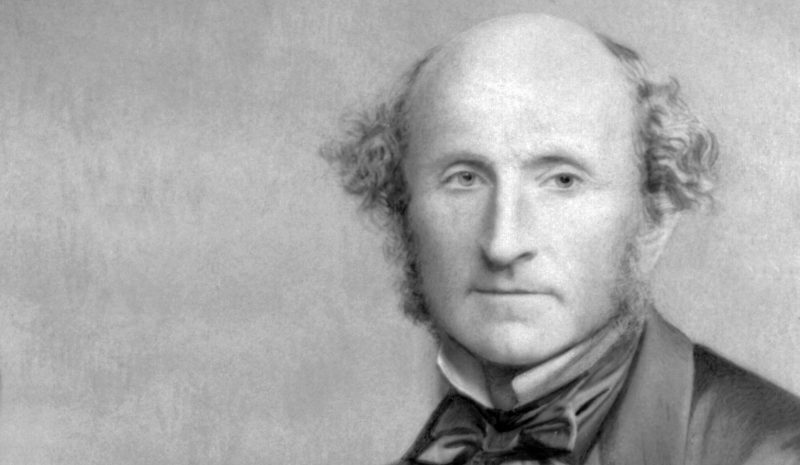

For example, 19th century liberal political philosopher John Stuart Mill is now widely admired by conservative and libertarian writers and academics as a proponent of individual economic liberty, the free market, and a flat tax. And they are not wrong, he was all of that, in his early thought. (Mill later supported several socialist causes.) Many of his other political views might be denounced by quite a few as the excesses of campus activist leftism. Adam Gopnik summarizes the Victorian philosopher’s generous slate of positions:

Mill believed in complete equality between the sexes, not just women’s colleges and, someday, female suffrage but absolute parity; he believed in equal process for all, the end of slavery, votes for the working classes, and the right to birth control (he was arrested at seventeen for helping poor people obtain contraception), and in the common intelligence of all the races of mankind. He led the fight for due process for detainees accused of terrorism; argued for teaching Arabic, in order not to alienate potential native radicals.…

Can people to Mill’s left on economics learn something from him? Sure. Can people to his right on nearly everything else learn a thing or two? It’s worth a shot. Mill championed engaging those with whom we disagree (he greatly admired Thomas Carlyle; the two couldn’t have been more different in many respects). He also argued vigorously for “’liberty of the press’ as one of the securities against corrupt or tyrannical government.” Before nodding your head in agreement—read Mill’s arguments. He might not agree with you.

And what did John Stuart Mill read? In Chapter One of his autobiography, Mill gives a detailed account of his classical education from ages 3–7, during which time he read “the whole of Herodotus,” “the first six dialogues of Plato,” “part of Lucian,” all in their original Greek, of course, as any young gentleman of the time would. Mill’s father, Scottish philosopher James Mill, intentionally set out to create a genius with this advanced course of study.

Lapham’s Quarterly excerpted the passage, and turned the many books Mill mentions into a list called “Early Education.” You can find all of the titles below, including the ancients mentioned and over two dozen “modern” works (that is, since the time of the Renaissance) Mill read as a child in English, including Cervantes’ mammoth Don Quixote. Most of us will have to make do with translations of the Greek texts, but take heart, even Mill “learnt no Latin until my eighth year.” The list shows not only Mill’s daunting precocity, but also how essential classical texts were to well-educated Europeans of any age.

It also highlights what kinds of texts were valued by Mill’s society, or at least by his father. All of the authors but one are men, all of them are Europeans, most of the works are histories and biographies. Given Mill’s broad views, his own recommended reading list might look different. Nonetheless, Mill’s account of his extraordinary early years gives us a fascinating look at the relative breadth of a liberal education in 19th century Britain. What ancient authors did you read as a young student? Or do you read now, between books, essays, articles, or Twitterstorms du jour?

In Greek

Aesop–The Fables

Xenophon–The Anabasis, Memorials of Socrates, The Cryopadeia

Herodotus–The Histories

Diogenes Laertius–some of The Lives of Philosophers

Lucian–various works

Isocrates–parts of To Demonicus and To Nicocles

Plato--Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Cratylus, Theaetetus

In English

William Robertson–The History of America, The History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V, The History of Scotland During the Reigns of Queen Mary and King James VI

David Hume–The History of England

Edward Gibbon–The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Robert Watson–The History of the Reign of Philip II, King of Spain

Robert Watson and William Thompson–The History of the Reign of Philip III, King of Spain

Nathaniel Hooke–The Roman History, from the Building of Rome to the Ruin of the Commonwealth

Charles Rollin–The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians

Plutarch–Parallel Lives

Gilbert Burnet--Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Time

The Annual Register of World Events, A Review of the Year (1758–1788)

John Millar–An Historical View of the English Government

Johann Lorenz von Mosheim–An Ecclesiastical History

Thomas McCrie–The Life of John Knox

William Sewell–The History of the Rise, Increase, and Progress of the Christian People Called Quakers

Thomas Wight and John Rutty–A History of the Rise and Progress of People Called Quakers in Ireland

Philip Beaver–African Memoranda

David Collins–An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales

George Anson–A Voyage Round the World

Daniel Defoe–Robinson Crusoe

The Arabian Nights and Arabian Tales

Miguel de Cervantes–Don Quixote

Maria Edgeworth–Popular Tales

Henry Brooke–The Fool of Quality; or the History of Henry, Earl of Moreland

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person

Introduction to Political Philosophy: A Free Yale Course

Leo Strauss: 15 Political Philosophy Courses Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness