A fascinating 20th century literary strain, “documentary poetics,” melds journalistic accounts, photography, official texts and memos, politics, and scientific and technical writing with lyrical and literary language. Perhaps best exemplified by Muriel Rukeyser, the category also includes, at certain times, James Agee, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and—currently—Claudia Rankine and “powerhouse” new poet Solmaz Sharif. It does not include Edgar Allan Poe, famously alcoholic 19th century master of the macabre and “father of the detective story.”

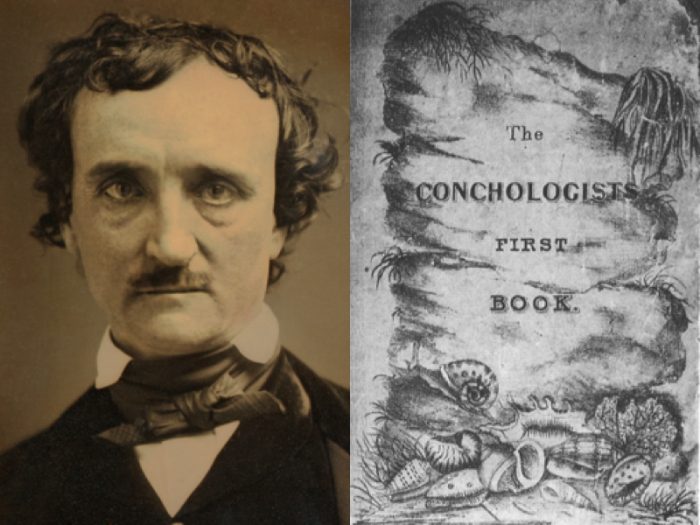

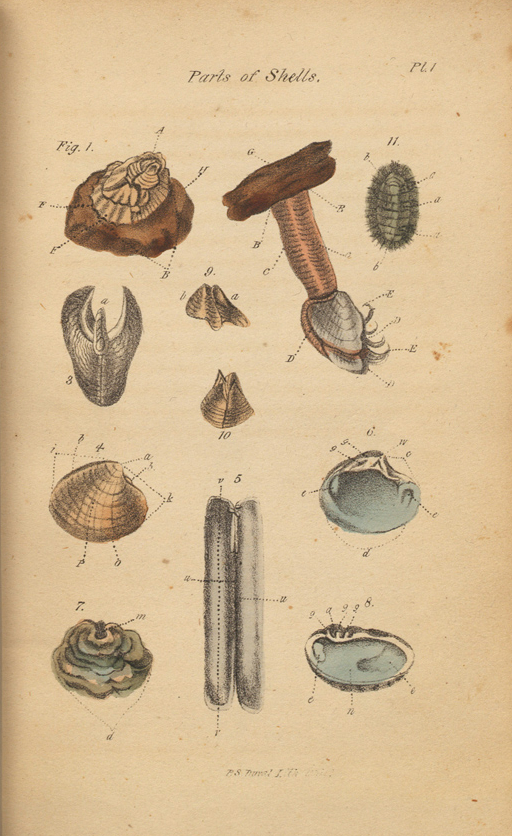

But you’ll forgive me for thinking, excitedly, that it just might, when I learned Poe had published a text called The Conchologist’s First Book (1839), a condensation, rearrangement, and “remixing,” as Rebecca Onion writes at Slate, of “an existing… beautiful and expensive” science textbook, Thomas Wyatt’s Manual of Conchology, including the original plates and a “new preface and introduction.”

My mind reeled: what wondrous horrors might the morose, romantic Poe have contributed to such an enterprise, his best-selling work, it turns out, in his lifetime. (For which Poe was paid $50 and, typically, received no royalties). What kind of experimental madness might these covers contain?

As I might have assumed from the book’s total obscurity, Poe’s writerly contributions to the project were meager. For all his genius as a storyteller, he could be a long-winded bore as an essayist. It seems he thought this aspect of his voice was best suited to the original writing he did for Conchologist’s First. His biographers, notes University of Houston professor emeritus John H. Lienhard, all “mutter an embarrassed apology for Poe’s shady side-track—then hurry back to talk about The Raven.” Onion quotes one biographer Jeffrey Meyers, who writes, “Poe’s boring pedantic and hair-splitting Preface was absolutely guaranteed to torment and discourage even the most passionately interested schoolboy.”

As for its “shadiness,” the book also elicits embarrassment from Poe devotees because, as esteemed biologist and historian of science Stephen J. Gould wrote in his exculpatory essay “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” it was “basically a scam,” though “not so badly done” as most allege. The naturalist Wyatt, a friend of Poe’s, had begged his publisher to release an abridged student edition of his original lavish and pricey $8 textbook, which had not sold well. When the publisher balked, Wyatt contracted Poe to lend his name and considerable editorial skill to a more-or-less bootleg “CliffsNotes” version to be sold for $1.50. To make matters worse, Poe and Wyatt were both accused of plagiarism, having “lifted chunks of their book from an English naturalist, Thomas Brown,” Lienhard points out.

Gould defended Poe as a rewriter of others’ work. “Yes, Poe plagiarized,” as Lienhard summarizes the argument. He presented Brown’s, and Wyatt’s, work as his own, but, “fluent in French, [he] went back to read Georges Cuvier, the great French naturalist” and made his own translations. He wrote his own introductory material, and he reorganized Wyatt’s book in such a way as to provide “genuinely useful insight into biological taxonomy.” Poe’s edition—with its “formidable subtitle,” A System of Testaceous Malacology, arranged Expressly for the Use of Schools—actually proved a hit with students, and likely not only because it sold cheap. It was the only publication in Poe’s lifetime to make it to a second edition.

Maybe humanist readers approach the work with biases firmly in place, expecting a genre that’s dry by its very nature to contain all the literary brilliance and entertaining intrigue of “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Lienhard suggests as much, describing irritation at how his “literary friends” ignore the scientific work of writers like Thoreau, Thomas Paine, Goethe, and poet Oliver Goldsmith. “Poe’s excursion into natural philosophy,” he writes, “was an embarrassment to people who are embarrassed by science in the first place.” Maybe.

Both Gould and Lienhard shrug off the less-than-scrupulous circumstances of the book’s creation, the latter citing a “cynical remark” by playwright Wilson Mizner: “If you steal from one author, it’s plagiarism. If you steal from many, it’s research.” At least he doesn’t go as far as Mark Twain, who once wrote in defense of Helen Keller, after she was charged with literary borrowing, “the kernel, the soul—let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterance—is plagiarism.”

Read the first, 1839 edition of The Conchologist’s First Book, published under Edgar A. Poe, at the Internet Archive, and the revised second, 1840 edition at Google Books.

Related Content:

Download The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe: Macabre Stories as Free eBooks & Audio Books

Mark Twain’s Patented Inventions for Bra Straps and Other Everyday Items

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness