If genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains, Glenn Gould merits each and every one of the many applications of the word “genius” to his name. The world knows that name primarily as one of a genius of the piano, of course, especially when interpreting the genius of Johann Sebastian Bach, but he also made an impression in his homeland of Canada as a genius of the radio editing suite. Having recorded for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s classical-and-jazz record label CBC Records placed him well to realize his ideas on the CBC’s airwaves, most memorably in the form of The Idea of North, an hourlong meditation on the vast, cold expanse that constitutes the top third of the country, which first aired on December 28, 1967.

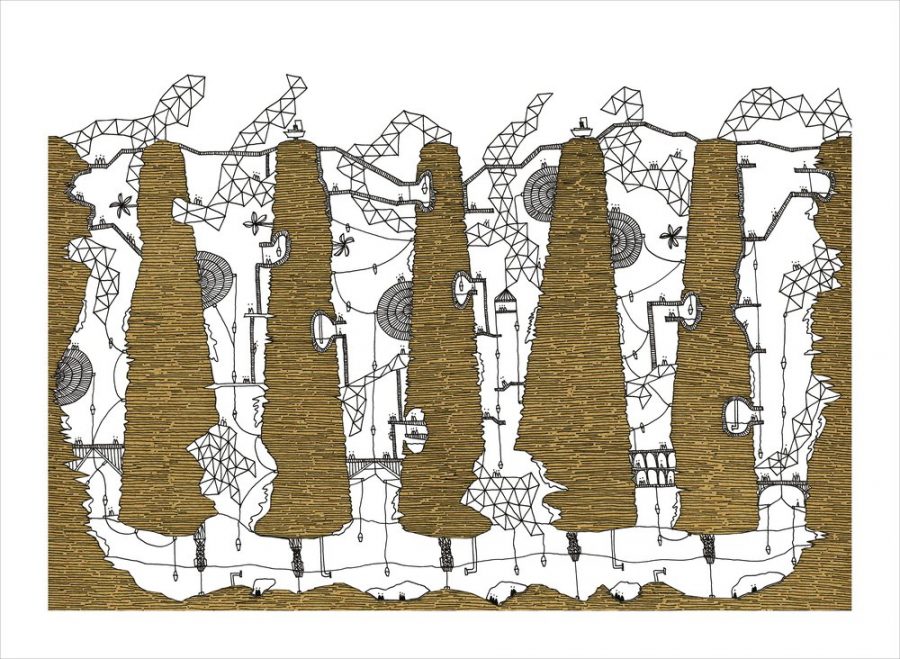

The broadcast’s fiftieth anniversary has prompted Canadians and non-Canadians alike to have another listen to Gould’s best-known radio project, back then shockingly experimental and still boldly unconventional today. “The pianist used a technique he called ‘contrapuntal radio,’ layering speaking voices on top of each other to create a unique sonic environment situated in the space between conversation and music,” says the site of CBC’s Ideas, which recently aired a new episode about the making of The Idea of North called Return to North.

The page quotes Gould biographer Geoffrey Payzant as describing it and Gould’s subsequent documentaries as “hybrids of music, drama, and several other strains, including essay, journalism, anthropology, ethics, social commentary, [and] contemporary history.”

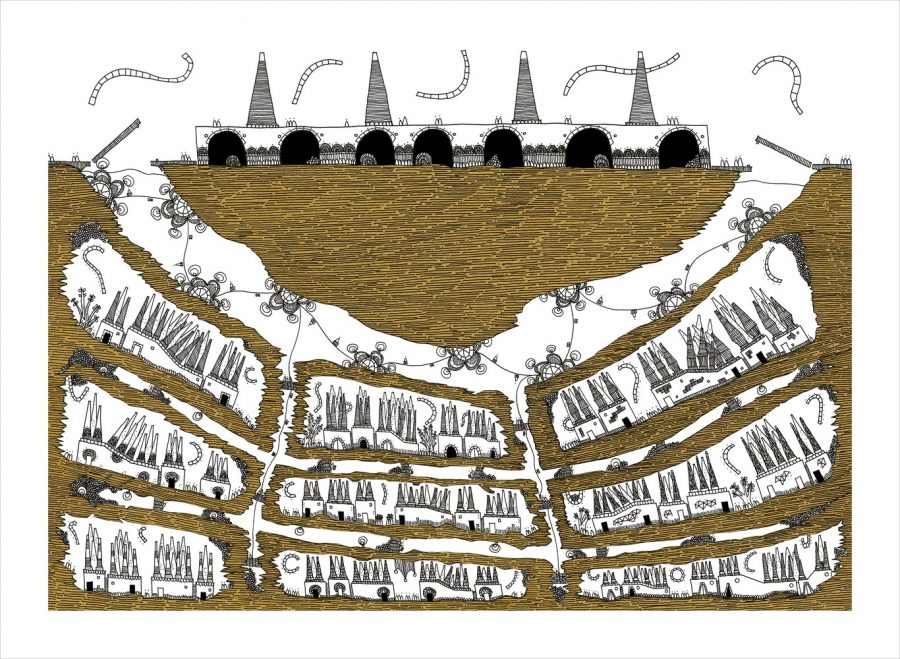

One might might well compare The Idea of North’s form to that of a fugue, the type of complex contrapuntal composition so closely associated with Bach and thus with Gould as well. But the form also serves the substance, “that incredible tapestry of tundra and taiga which constitutes the Arctic and sub-Arctic of our country,” as Gould himself puts it in the broadcast’s introduction. “I’ve read about it, written about it, and even pulled up my parka once and gone there,” he continues, but like most Canadians remained ever “an outsider” to the North, “and the North has remained for me, a convenient place to dream about, spin tall tales about, and, in the end, avoid.”

The North also offered Gould a powerful symbol of solitude, a condition which he sought throughout his life, especially after quitting live performance to focus exclusively on the studio shortly before making The Idea of North. In the decade thereafter he made two more formally and thematically similar documentaries, one on coastal Newfoundlanders and another on Mennonites in Manitoba, and the three together make up his “Solitude Trilogy.” A television film of The Idea of North, co-produced by the CBC and PBS, appeared in 1970, layering images of the North atop of the words about the North Gould had collected. It certainly adds a dimension to Gould’s painstakingly constructed audio collage, but somehow pure radio, the old “theater of the mind,” still suits it best: the images of the North he wanted to evoke, one senses just as well now as half a century ago, exist only in the mind.

Related Content:

Glenn Gould Explains the Genius of Johann Sebastian Bach (1962)

Watch a 27-Year-Old Glenn Gould Play Bach & Put His Musical Genius on Display (1959)

Glenn Gould Gives Us a Tour of Toronto, His Beloved Hometown (1979)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.