As a callow young art student in high school, I dearly wanted, and tried, to see the world with the same furious intensity as Vincent van Gogh, and to capture that kind of vision on paper and canvas. I later realized with chagrin as I stood in a line several blocks long for a wildly popular exhibit (Van Gogh’s Van Goghs at the National Gallery of Art) that I was but one of millions who wanted to see the world through Van Gogh’s eyes.

After waiting for what seemed like forever, not only could I barely get a glimpse of any of the paintings through the scrum of tourists and gawkers, but I felt—in my protective bubble of Van Gogh veneration—that these people couldn’t possibly get Van Gogh the way I got Van Gogh.

Well, everybody has their own version of Van Gogh, perhaps, but one I’ve outgrown is the mad, magical genius whose mental illness acted as a tragic but necessary condition for his transcendently passionate work. Maybe it’s age and some familiarity with life’s hardship, but I no longer romanticize Van Gogh’s suffering. And perhaps a more realistic view of what was likely debilitating bipolar disorder has given me an even greater appreciation for his accomplishments. During the brief 10-year period that Van Gogh pursued his art, he was as dedicated as it’s possible to be—producing nearly 900 canvases and over 1,100 works on paper, and altering the way we see the world, all while experiencing severely crippling bouts of depression, anxiety, and self doubt; having his neighbors ostracize and evict him from his home; and spending most of his final year in an institution.

Sadly, he felt himself a mediocrity at best, a failure at worst. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art writes, “in 1890,” the final year of his life, “he modestly assessed his artistic legacy as of ‘very secondary’ importance.” (This despite the appreciation he’d begun to receive from several gallery showings.) The posthumous reception of his work—ubiquitously reproduced and admired by countless throngs in exhibit after exhibit—can do nothing now to lift his spirits, but surely vindicates his prodigious effort. Van Gogh’s fame has had the unfortunate side effect of crowding out many students of his art from gallery exhibitions. Yet this difficulty need not now prevent them from surveying and seeing up close his huge body of work in digital archives like that of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the largest Van Gogh collection in the world.

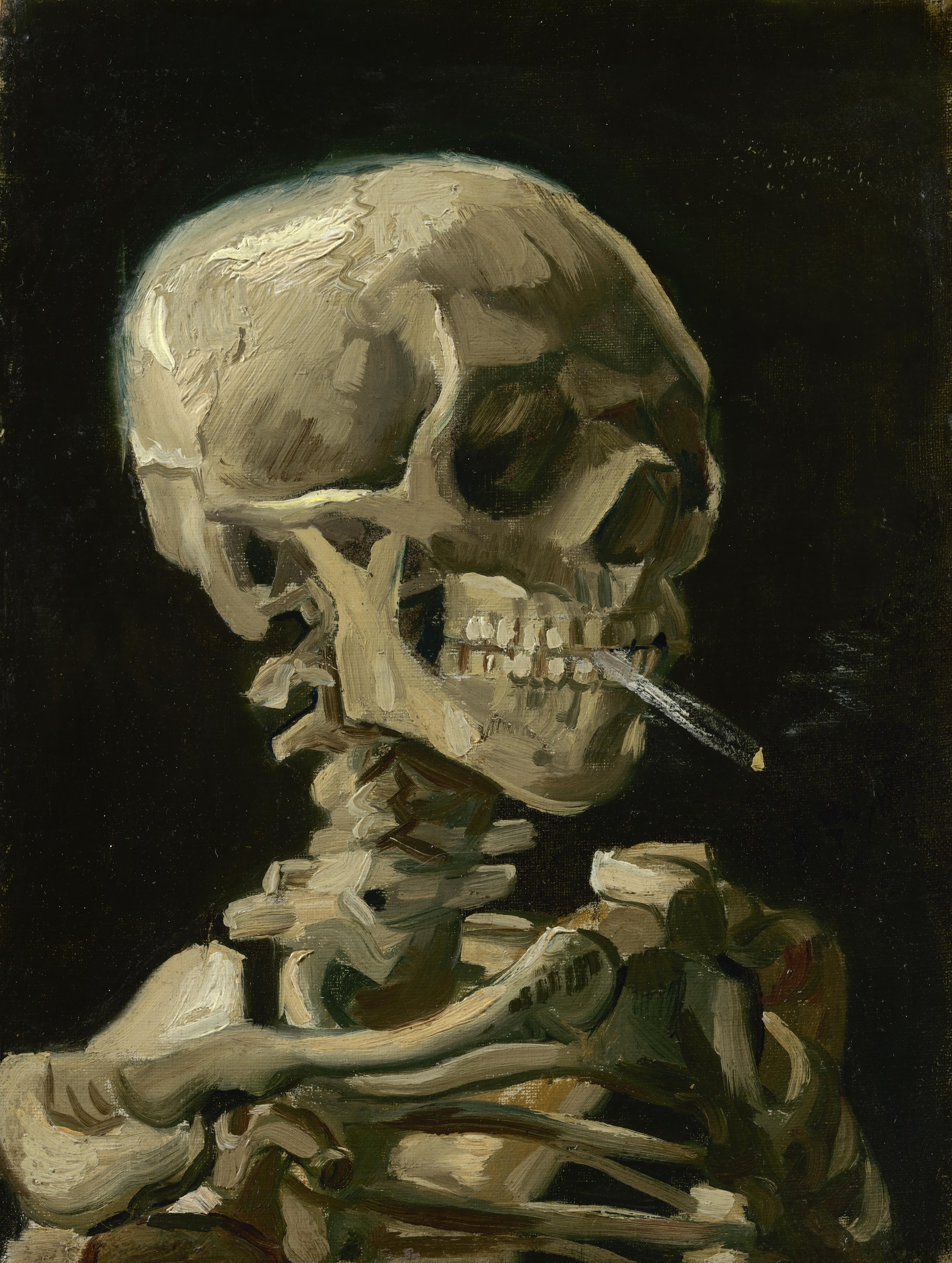

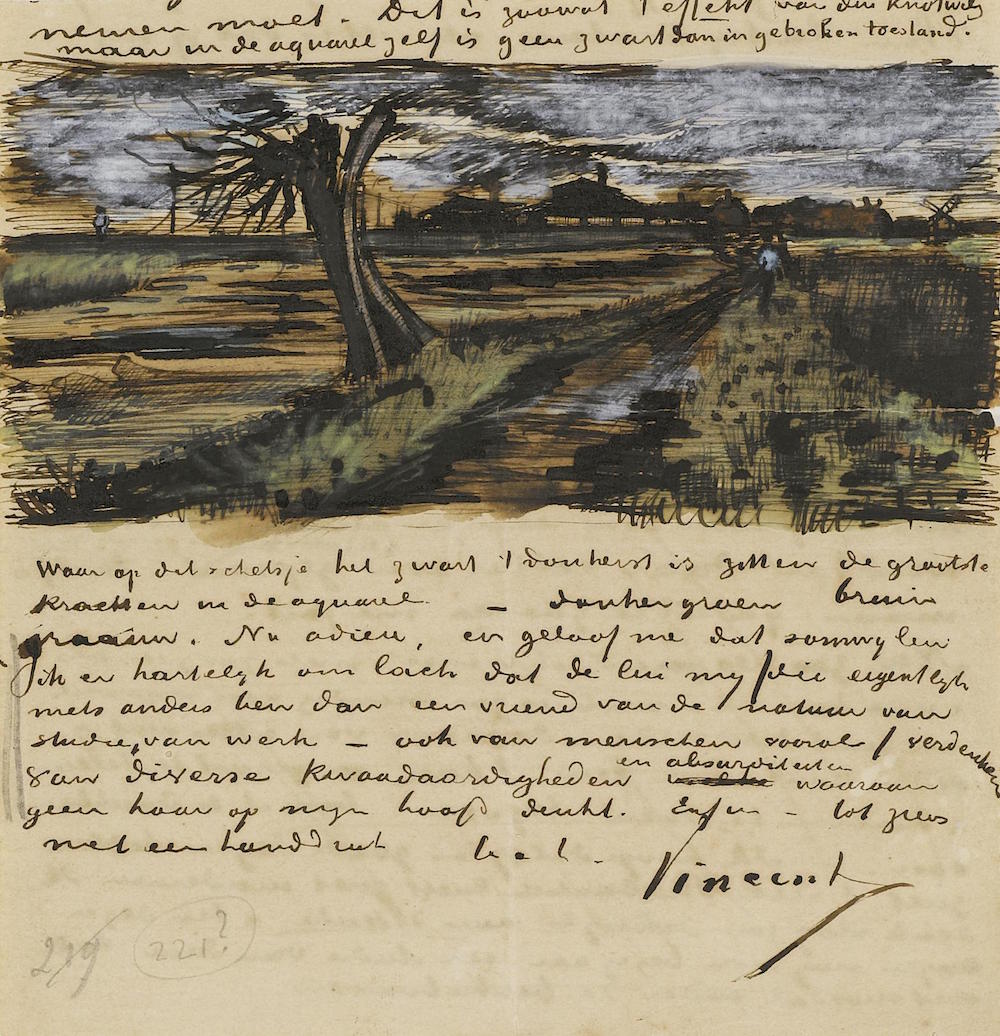

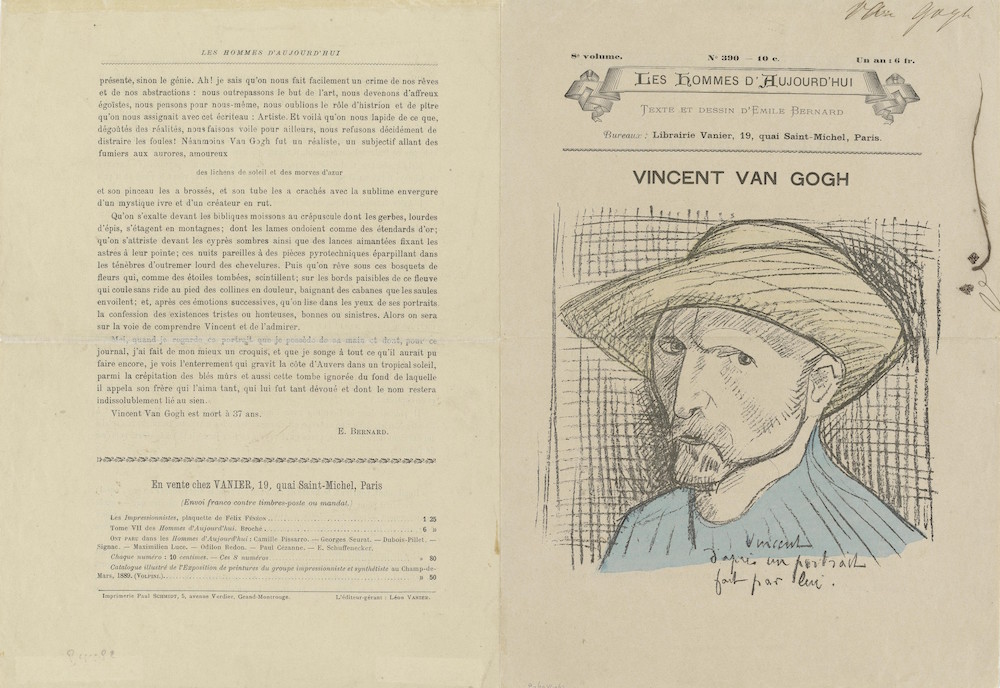

By entering the collection, you can see, for example, Self Portrait with Straw Hat, at the top, from 1887, or the strikingly similar portrait of his brother and staunch supporter Theo from the same year, just below it. Further down is the darkly humorous Head of a Skeleton With a Burning Cigarette from 1886, and just above, see an 1882 letter to Theo, with a beautiful sketch of a Pollard Willow, an image he committed to canvas that year. Just below, see an interesting example of the very beginnings of Van Gogh’s posthumous canonization—an 1891 cover sketch and short tribute article in the French satirical magazine Les hommes D’Aujourd’hui.

You can search or browse the collection, and download and view these images, and many hundreds more paintings, sketches, drawings, letters, and much more, in resolution high enough to zoom in to every individual brushstroke and ink pen flourish. [When you click on an image in the collection, look for the down arrow ↓ that lets you start a download.] Missing from the experience is the three-dimensionality of Van Gogh’s heavily textural painting, but nowhere else will you have this level of accessibility to so much of his work and life.

And if you feel, as I once did, a need to get inside that life and walk around a bit, a new Art Institute of Chicago exhibit will allow you to do just that, with a three-dimensional recreation of his painting The Bedroom, including, writes This is Colossal, “all the details of the original painting, arranged in haphazard alignment to imitate the original room.” (The more morbidly curious can see a living replica of his infamous ear, recreated using his own DNA.) The room went up for rent on AirBnB yesterday. Best of luck getting a reservation.

Related Content:

Van Gogh’s 1888 Painting, “The Night Cafe,” Animated with Oculus Virtual Reality Software

The Unexpected Math Behind Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”

Artist Turns a Crop Field Into a Van Gogh Painting, Seen Only From Airplanes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness