We now find ourselves about a third of the way through March, more interestingly known as Women’s History Month, a time filled with occasions to round up and learn more about the creations and accomplishments of women through the centuries. And “who better to honor this March than history’s influential feminists?” writes Lynn Lobash on the New York Public Library’s website.

We’ve previously featured treasures from the New York Public Library, including art posters, maps, restaurant menus, theater ephemera, and a host of digitized high-resolution images. Today it’s time to highlight one of the many recommended reading lists that the NYPL’s librarians regularly create for the reading public. “Know Your Feminisms”–a book list “essential for understanding the history of feminism and the women’s rights movement”–could easily be used in a Feminism 101 course. It runs chronologically, beginning with these ten volumes (the quoted descriptions come from Lynn Lobash):

- A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929). “This essay examines the question of whether a woman is capable of producing work on par with Shakespeare. Woolf asserts that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’ ”

- The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1949). “A major work of feminist philosophy, the book is a survey of the treatment of women throughout history.”

- The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan (1963). “Friedan examines what she calls ‘the problem that has no name’ – the general sense of malaise among women in the 1950s and 1960s.”

- Les Guérillères by Monique Wittig (1969). “An imagining of an actual war of the sexes in which women warriors are equipped with knives and guns.”

- The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer (1970). “Greer makes the argument that women have been cut off from their sexuality through (a male conceived) consumer society-produced notion of the ‘normal’ woman.”

- Sexual Politics by Kate Millett (1970). “Based on her PhD dissertation, Millett’s book discusses the role patriarchy (in the political sense) plays in sexual relations. To make her argument, she (unfavorably) explores the work of D.H Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Sigmund Freud, among others.”

- Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (1984). “In this collection of essays and speeches, Lorde addresses sexism, racism, black lesbians, and more.”

- The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf (1990). “Wolf explores “normative standards of beauty” which undermine women politically and psychologically and are propagated by the fashion, beauty, and advertising industries.”

- Gender Trouble by Judith Butler (1990). “Influential in feminist and queer theory, this book introduces the concept of ‘gender performativity’ which essentially means, your behavior creates your gender.”

- Feminism is for everybody by bell hooks (2000). “Hooks focuses on the intersection of gender, race, and the sociopolitical.”

To see the very newest books the NYPL has put in this particular canon, the latest of which came out just last year, take a look at the complete list on their site. There you’ll also find “Well Done, Sister Suffragette!,” a shorter collection of five books on history’s fighters for women’s rights: the slave-turned-orator Sojourner Truth, activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, social reformer Susan B. Anthony, nineteenth amendment-promoter Alice Paul, and radical Catholic journalist Dorothy Day.

Note: You can download Gloria Steinem’s recent autobiography, My Life on the Road, as a free audiobook if you sign up for Audible.com’s free trial program. It’s narrated by Debra Winger and Steinem herself. Learn more about Audible’s free trial program here.

Related Content:

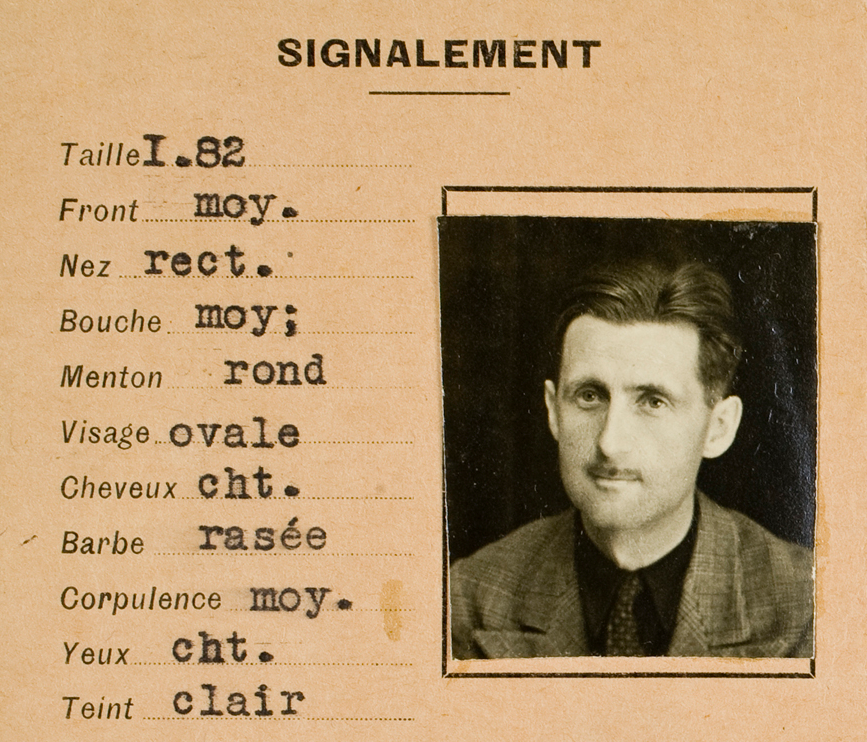

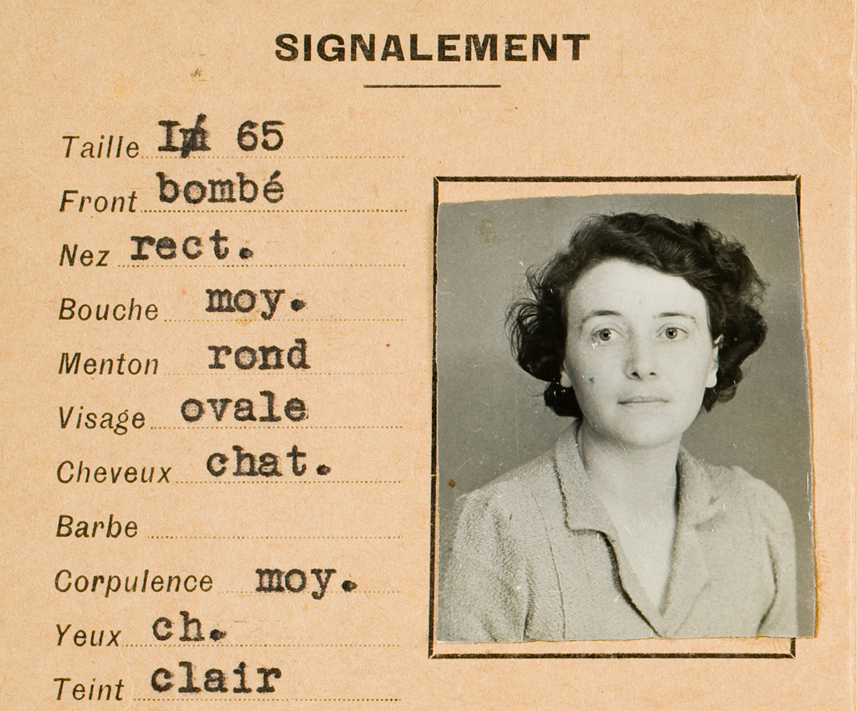

Simone de Beauvoir Explains “Why I’m a Feminist” in a Rare TV Interview (1975)

Simone de Beauvoir Tells Studs Terkel How She Became an Intellectual and Feminist (1960)

The First Feminist Film, Germaine Dulac’s The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922)

The Feminist Theory of Simone de Beauvoir Explained with 8‑Bit Video Games (and More)

100,000+ Wonderful Pieces of Theater Ephemera Digitized by The New York Public Library

Foodie Alert: New York Public Library Presents an Archive of 17,000 Restaurant Menus (1851–2008)

New York Public Library Puts 20,000 Hi-Res Maps Online & Makes Them Free to Download and Use

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.